Didi’s sexually aggressive ads have come back to haunt it

Didi is facing one of its biggest crises in company history.

Didi is facing one of its biggest crises in company history.

The furor surrounding a female passenger’s death—the second one this year—while using its carpooling service Hitch continues to dominate conversations in China this week, and people are blaming Didi for not doing enough to prevent attacks on its service.

Like UberPool, Hitch emerged in 2015 as a way for drivers to earn extra income by picking up passengers heading in the same direction. While it saw rapid growth, the volume of rides declined after the company pulled back incentives like free rides, prompting Didi to consider a change in strategy. That was when it started marketing the product to emphasize real-life social networking—and even dating.

As Huang Jieli—the woman who had served as Hitch’s general manager until she was demoted last week—said in an interview in 2015: “Like a coffee shop, or a bar, a private car can become a half-open, half-private social space. It’s a very sexy application scenario.” And in another interview (link in Chinese) in 2017, she said “the biggest motivation for our drivers is to share a trip with a passenger.”

The new messaging did indeed help Hitch grow. But perhaps Hitch grew so quickly that it became harder to respond to problems that arose. Though the service added new safety features, the driver that police are investigating for the robbery, rape, and murder of the female passenger whose body was found this month had received another complaint just a day prior to the incident—a shortcoming Didi had acknowledged and apologized for. Didi has indefinitely suspended Hitch and is conducting a review of the service.

In the wake of the woman’s death, Chinese internet users have resurfaced sexually suggestive (and borderline explicit) ads from Didi that in retrospect seemed like a wink to drivers that they could use the platform to meet women. The ads, some of which date back more than four years, were meant to be humorous, but in light of the recent deaths, are viewed as tone deaf and tacky.

Here is a selection of the Didi ads drawing outrage online that have been verified by Quartz to be authentic.

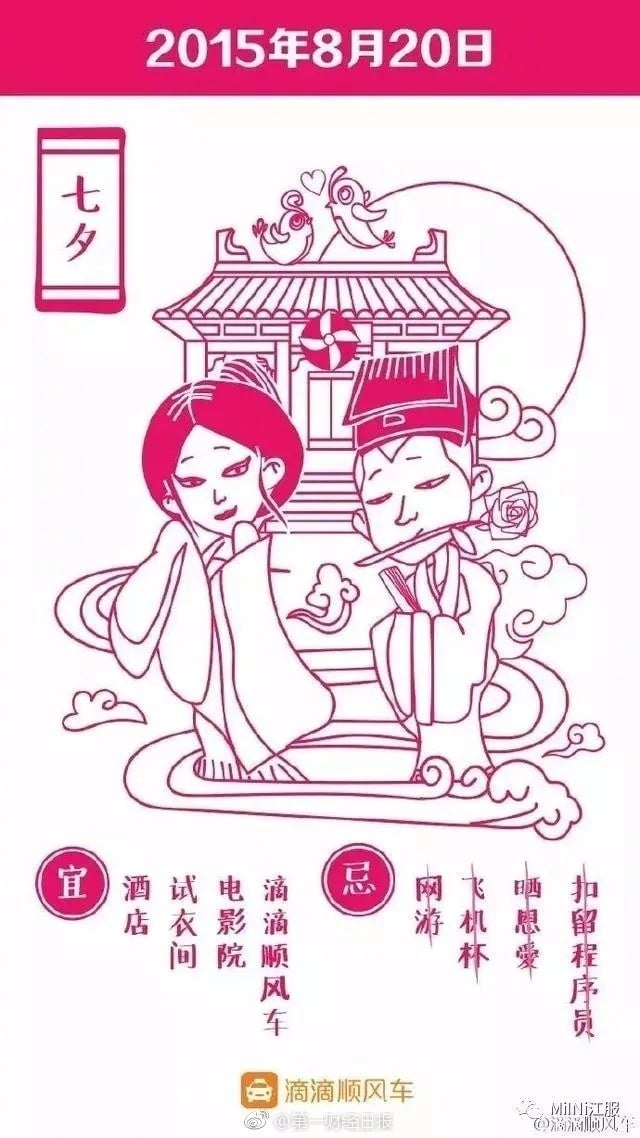

Hooking up on Chinese Valentine’s Day

In August 2015, Hitch rolled out an ad for Qixi, considered China’s Valentine’s Day, depicting the forlorn couple at the heart of the festival’s origin story. The ad said the day was for four things: hotels, fitting rooms, cinema, and Didi’s Hitch. The ad appeared to be a nod to a viral sex tape shot in a Uniqlo fitting room in Beijing that was released shortly before. It also noted that Chinese Valentine’s Day was not a good day for keeping programmers busy, showing off relationships, masturbation cups, or online games.

Another series of ads, released for the same festival, is filled with more messaging around dating. In one, the text says, “I am more afraid of you not asking [me] out for a date than being tagged,” while another simply reads, “Let’s date.” The service had a feature on the app that let drivers tag passengers with phrases like “long legs” and “hot as hell.” All Hitch drivers were able to read the tags, which have since been removed from the app, and they were also able to specify a preference for female or male passengers, Chinese financial outlet Caixin reported in May (paywall, link in Chinese).

Free rides for short skirts

The ads got more brazen from there.

When Hitch added a feature letting drivers waive fares for passengers, it saw another marketing opportunity. In one ad, Didi asked three female passengers why they thought they should be given free rides. One woman in a black suit responded “because I am very womanly” while a woman in a low-cut dress answered: “Is this reason enough?”

In another ad, a driver explained why he would waive a passenger’s fare. “You have one skirt, and I have warm wind.” Warm wind is likely a play on words, referring to a car’s heater as well as yang, a Chinese philosophical concept representing maleness, compared with the feminine yin.

Sleep with me

Such explicit ads weren’t just for Hitch.

Before Hitch was launched, Didi had run an innuendo-laden ad that asked: “Are you wet? Are you tight? Are you hard?” It appears to be from before 2014 because it shows Didi’s former Chinese name, which it changed that year amid a trademark dispute (link in Chinese).

In it, a cartoon man is standing in the rain, who in spite of being in a hurry, has been unable to hail a taxi. He is asked if he’s wet because of the rain, if he’s tight because his watch is squeezing his wrist, and if he’s hard because his legs have turned to stone—one of the ways to refer to muscle fatigue in Chinese.

And in 2016, an ad pegged to World Sleep Day showed only text on a white background that read: “A spring wind that blows 10 miles couldn’t compare to sleeping with you.” Spring wind in Chinese also refers to animals waking from their winter hibernation and mating.

Gone too far

It’s unclear who made the final calls to approve these advertisements, but a Didi representative said it began taking down marketing materials “that could be considered inappropriate” starting in early 2016, when it began reviewing its ad campaigns and “disciplining the wrong kinds of content and responsible persons.”

The problem of sexual assault on ride-hailing apps isn’t unique to China—Uber, for example, has grappled with safety issues in countries like India and Mexico—but Didi’s cofounders in an apology noted they were operating in a competitive startup environment. “We raced non-stop riding on the force of breathless expansion and capital through these few years,” said its cofounders, Liu Qing and Cheng Wei, in a statement this week. “The only thing we can do at this moment of pain is to face the pain and take on our responsibility.”

As Didi does damage control, it’s hoping the backlash won’t be so fierce as to derail the business. Already, people have begun a #DeleteDidi (link in Chinese) campaign on the Chinese social network Weibo, and Didi’s app ranking has fallen (link in Chinese) from ninth to 61st on China’s iOS app store—its worst since May, when another female passenger was murdered.