Argentina’s unofficial consumer confidence metric is free-falling again

After a quiet summer, Argentina’s acute currency and consumer confidence problems are heating up dangerously.

After a quiet summer, Argentina’s acute currency and consumer confidence problems are heating up dangerously.

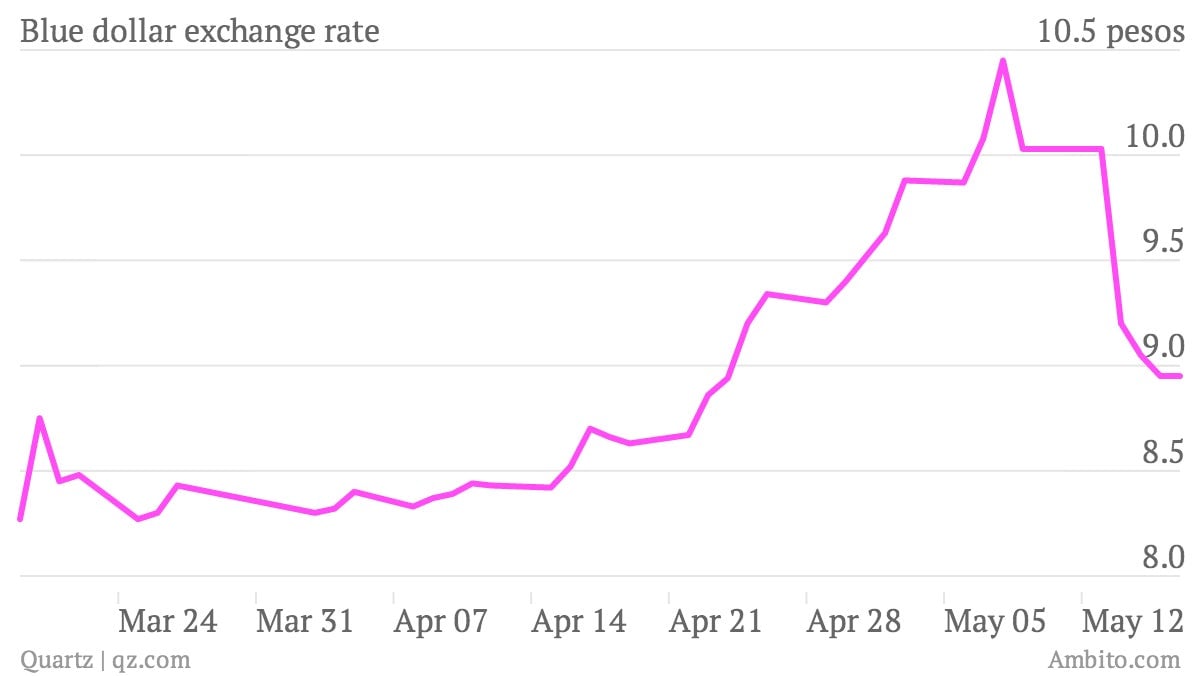

Earlier this year, Argentines rushed to exchange their local currency for anything that held its value better than the peso: real estate, cars, bitcoins—but mostly US dollars—amid fears that the government would default on its debt and devalue the peso, like it did back in 2001. The feverish demand for US dollars, however, came with a price. Anyone who wanted greenbacks had to pay an almost 100% premium for them; while the official exchange rate hovered near five pesos to the dollar, the unofficial rate, often referred to as the blue dollar rate, soared upwards of 10 pesos to the dollar.

Soon thereafter, demand eased and the black market rate tumbled below 10 pesos the dollar, eventually falling to nine pesos to the dollar and at a couple points—in mid June and then early July—even fell below eight pesos to the dollar. But those days are long gone. Barely five months later, demand is soaring and the black market dollar rate is back up above 10, as inflation fears have intensified again.

This is bad news for Argentina.

The problem, simply put, is Argentina isn’t prepared to deal with any more panic. While the government has worked to normalize some of its relationships with international financial institutions which it spurned back in 2001, the country’s economic outlook is still troubled at best. Its foreign reserves have been falling fast, and it still has plenty of outstanding debt to deal with. The less Argentines buy into the country’s financial system, the more difficult it will be for Argentina to source the cash it needs.

President Cristina Kirchner knows it better than anyone. Since 2011, she has enacted over 30 measures to curb US dollar hoarding in Argentina, which came to be known as “the dollar clamp.” She’s tried everything from questionable bond offerings to even more questionable pseudo currencies. Little, however, has seemed to work. (The dollar clamp has forced Argentines to turn to the black market if they want to buy dollars.)

The peso is tumbling in advance of Argentina’s Oct. 27 mid-term election, in which it will elect half of the country’s lower house and a third of its senate. If the August 11 primaries were any indication of what’s to come, support for Kirchner’s Victory Front coalition is likely to fall further.