As countries race to put self-driving cars on road, these vehicles, like human drivers, will inevitably one day be in sole charge of split-second decisions that will result in life or death. Sometimes any decision will unavoidably cause harm to one set of people or another—the famous trolley problem. In that case, what human preferences should shape the algorithms that will decide what the car will do?

Researchers from MIT’s Media Lab have found the answer to that can be quite different depending whether if you’re from the United States, France, or Japan, and hope that knowledge will shape “a global conversation to express our preferences to the companies that will design moral algorithms, and to the policymakers that will regulate them.”

“Never in the history of humanity have we allowed a machine to autonomously decide who should live and who should die, in a fraction of a second, without real-time supervision,” they wrote.

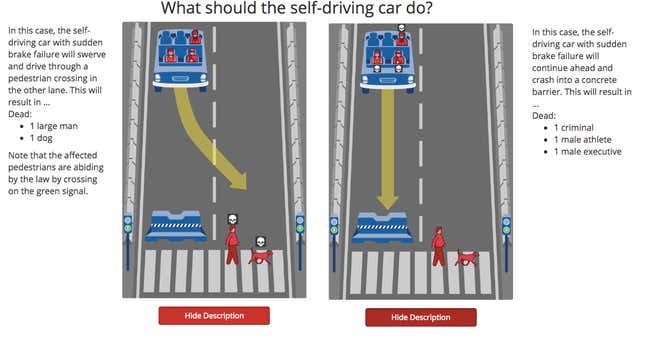

The researchers deployed a survey called the Moral Machine in 2016. It created 13 scenarios in which death is inevitable for one group of people or another when a car’s braking system malfunctions. One group might be three elderly people crossing a street, while the other is two adults and a child in a car. The idea was to find out what ethical instincts people expressed when faced with these dilemmas. Some 2.3 million participants from 233 countries have taken the survey, generating 40 million decisions. An analysis of responses from the 130 countries with at least 100 responses was published in scientific journal Nature last Wednesday (Oct .24). (Separately, they created a tool that allows the ranks of 117 countries to be seen across various preferences.)

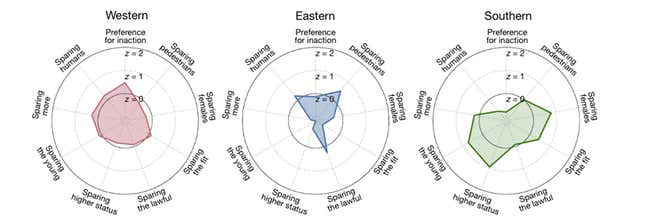

The researchers found the responses allowed countries to be broadly clustered into Western, Eastern, and Southern groups, with clear differences among them.

Young versus old

The Western group, which included the United States, much of Europe, and also African nations like Kenya and South Africa, showed a marked preference for saving children. Canada was in 29th place for wanting to save the young, the UK was in 34th place, and South Africa was in 38th place.

The Eastern cluster, which included countries shaped by hierarchical norms, such as the Confucian values of China, Japan, and South Korea, as well as socially conservative Middle Eastern and South Asian countries, where respect for older members of society is emphasized, were more likely to prefer saving older people over saving the young. In terms of saving the young over the old, China (115th), South Korea (110th), Japan (103rd), and India (99th) ranked near the bottom in expressing a preference to do so.

Saving more people

Countries in the Western cluster were generally for saving more people. The US, for example, ranked near the top, 14th, in terms of wanting to save more people, while Japan (117th) and China (113rd) were at the other extreme. Researchers said participants from individualistic cultures were more likely value saving more people.

Pedestrians versus passengers

Most countries in the Eastern group strongly preferred saving pedestrians—Japan ranked first among all nations, followed closely by Jordan, Palestine, and Iran—as well as sparing the lawful, a reflection perhaps of more collectivist, conformist social mores of these countries. People in Western countries were less likely to want to save pedestrians over car passengers.

Women versus men

Meanwhile the Southern cluster, which encompassed Latin American countries, France, and nations with French influence, expressed a strong preference for saving women over men. France ranked 2nd for wanting to save women, compared with Germany (74th), which is in the Western group. Eastern nations also didn’t have a preference for saving women.

To be sure…

Of course, not all countries in a particular geographic cluster behave the same way, and some countries share characteristics with nations in other clusters. For example, when it comes to sparing pedestrians or passengers in a car, Japan ranked first, putting a higher value on saving people on the street than any other country that responded. That made it much more similar to Norway (13th) than its Asian peer China (116th).

Meanwhile the value placed in China on saving the lawful (ranking 9th) was far different than in India (97th), both in the same geography, and group-oriented.

While the research is fascinating, Bryant Walker Smith, a law professor at the University of South Carolina in Columbia argued it’d be rare for a vehicle to face such binary choices. And in general, autonomous cars are expected to make roads far safer than they are now.

But Edmond Awad, an author of the report, hopes the research can help people think more deeply about not only autonomous driving, but also about whose values are shaping AI.

The breakdown between individual and collective cultures is “arguably the most important for policymakers to consider,” wrote the researchers (p.4) adding that “this split between individualistic and collectivistic cultures may prove an important obstacle for universal machine ethics.”