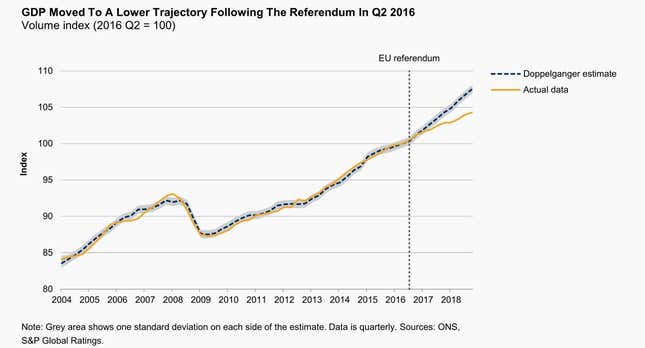

Brexit: When will it happen? How will it happen? Will it even ever happen? These seemingly unanswerable questions don’t need to be resolved to measure the impact that Brexit has had on the UK’s economy. (Or, rather, the idea of Brexit.) If the 2016 referendum to leave the European Union had gone the other way, the British economy would have been about 3% larger than it was at the end of 2018, according to S&P Global Ratings. The UK has forgone, on average, £6.6 billion ($8.7 billion) in economic activity in each of the 10 quarters since the vote.

The biggest impact of the vote to leave the EU was on the British pound, which remains 12% and 11% weaker against the US dollar and the euro, respectively. Economically speaking, the UK got the downsides of this depreciation without the upside: an increase in inflation that reduced household spending and no notable boost to trade.

Meanwhile, the uncertainty about what shape Brexit will take has “increasingly paralyzed” decision-making, which can be seen in the contraction of business investment in 2018, wrote Boris Glass, a senior economist at S&P, in the report published today.

To estimate the size of a Brexit-less Britain, S&P ventured into the upside-down world of econometrics known as the “Doppelgänger method.” This grafts together other economies that have similar characteristics to the UK to create a synthetic version of the UK’s economy. Then, the growth of the actual UK economy is compared with the alternative-universe UK economy after the June 2016 referendum.

The recipe for a Doppelgänger UK features a generous helping of the US and Canada, mixed in with Hungary, Japan, and others:

🇺🇸 28.4% of the US

🇭🇺 24.1% Hungary

🇨🇦 21.3% Canada

🇯🇵 14.5% Japan

🇩🇰 4.9% Denmark

🇮🇪 4.4% Ireland

🇵🇹 2.6% Portugal

S&P estimates that the actual UK economy was between 2.4% and 3.4% smaller at the end of 2018 than it would have been if the UK had voted to stay in the EU.

While the UK economy appeared resilient in the immediate aftermath of the referendum, Glass’s analysis says with hindsight it seems that the UK had almost immediately shifted to a slower-growth trajectory. Consumers weren’t particularly nervous about what the vote would mean, which would have showed up in an increase in precautionary savings; instead, they tapped into their savings to mitigate the impact of the increase in inflation drive by the fall in the pound.

S&P noted three likely reasons exports weren’t significantly boosted by the weaker pound, as some Brexit supporters predicted would happen. First, some exporters didn’t pass on lower prices. Second, many of the goods the UK exports include components that are imported, so the rising cost of these supplies negated the benefit of a weaker pound. Third, most of the UK’s exports are services, which are less sensitive to price changes than goods. This final point is important, as MPs debate the merits of the UK remaining in a customs union with the EU, while overlooking that the services industry is more important to the UK economy and benefits little from a goods-focused customs union.

It’s unclear whether a resolution to the current Brexit impasse will boost growth. The UK economy could rebound, but is unlikely to fully recoup its losses. Additionally, “some businesses have ventured well beyond the point of no return” by shifting staff and assets away from the UK in order to keep EU market access, S&P notes.

Looking for more in-depth coverage of Brexit? Sign up for a free trial of Quartz membership, and read our premium field guide on Brexit’s irreversible impact.