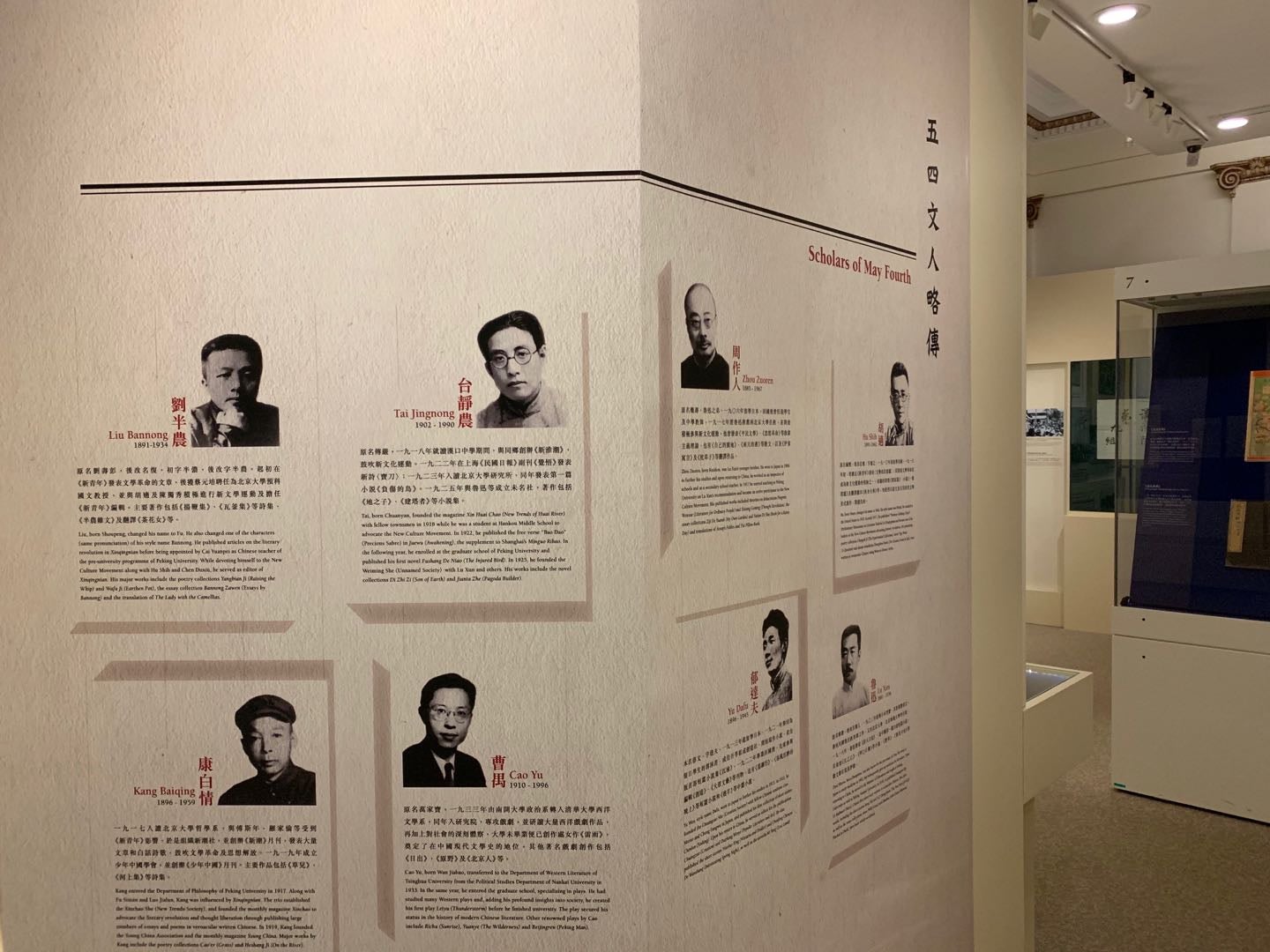

As dissent is silenced, Xi Jinping lauds a massive student rebellion 100 years ago

On this day 100 years ago, patriotic Chinese youth had a wish—that Western ideologies would rescue their society from feudalism, as well as the political chaos and foreign invasions that plagued the country. They placed their hopes in what they called “Mr. Democracy” and “Mr. Science.”

On this day 100 years ago, patriotic Chinese youth had a wish—that Western ideologies would rescue their society from feudalism, as well as the political chaos and foreign invasions that plagued the country. They placed their hopes in what they called “Mr. Democracy” and “Mr. Science.”

To make their voices heard, thousands of them took to the streets, a scene that is unimaginable in the tightly controlled environment of today’s China under president Xi Jinping. Yet the May Fourth Movement of 1919, as it later became known, continues to reverberate in China today, even as student movements of any kind are immediately snuffed out. The Chinese Communist Party today celebrates the actions of those students as a show of patriotism, while steering clear of the inherently rebellious nature of a movement that expressed people’s dissatisfaction with what they saw as a failing political system.

“Salvation from the darkness”

In 1911, China’s last imperial dynasty—the Qing court—was overthrown by revolutionaries who put in its place a Nationalist government with Sun Yat-sen as its provisional first president, and called the country the Republic of China. However, warlords continued to rule in different parts of China, and efforts by foreign powers, such as Japan, to retain or expand control over its territory continued.

Intellectuals like Chen Duxiu were among the first to call for the abolishment of what he felt were antiquated ideologies supported by Confucian traditions (link in Chinese), such as reverence for filial piety and superstitions, that stopped people from embracing progressive Western ideas.

At the start of 1919, Chen, then dean of the elite Peking University, wrote in New Youth magazine (link in Chinese) that he believed only democracy and science could save China. (Chen was also a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party but was expelled in 1929 for his support of democratic institutions.)

“Look at how much bloodshed and turmoil people in the West have undergone in order to support Mr. Democracy and Mr. Science, who have gradually saved them from darkness and led them to a brighter world. Now, we believe that only these two gentlemen can deliver salvation from the darkness in China, be it political, moral, intellectual, or spiritual. In support of these two gentlemen, we will not stand down in the face of government oppression,” Chen wrote in the magazine he had founded.

That year was a humiliation for China. It failed to take back sovereign control of the Shandong Peninsula at the post-World War I conference in Paris, after Western powers decided to let Japan keep the territory that it had seized from Germany in 1914—despite the fact that China fought on the side of the Allies. At that time, there also existed other foreign concessions in Shanghai and the southern city of Guangzhou.

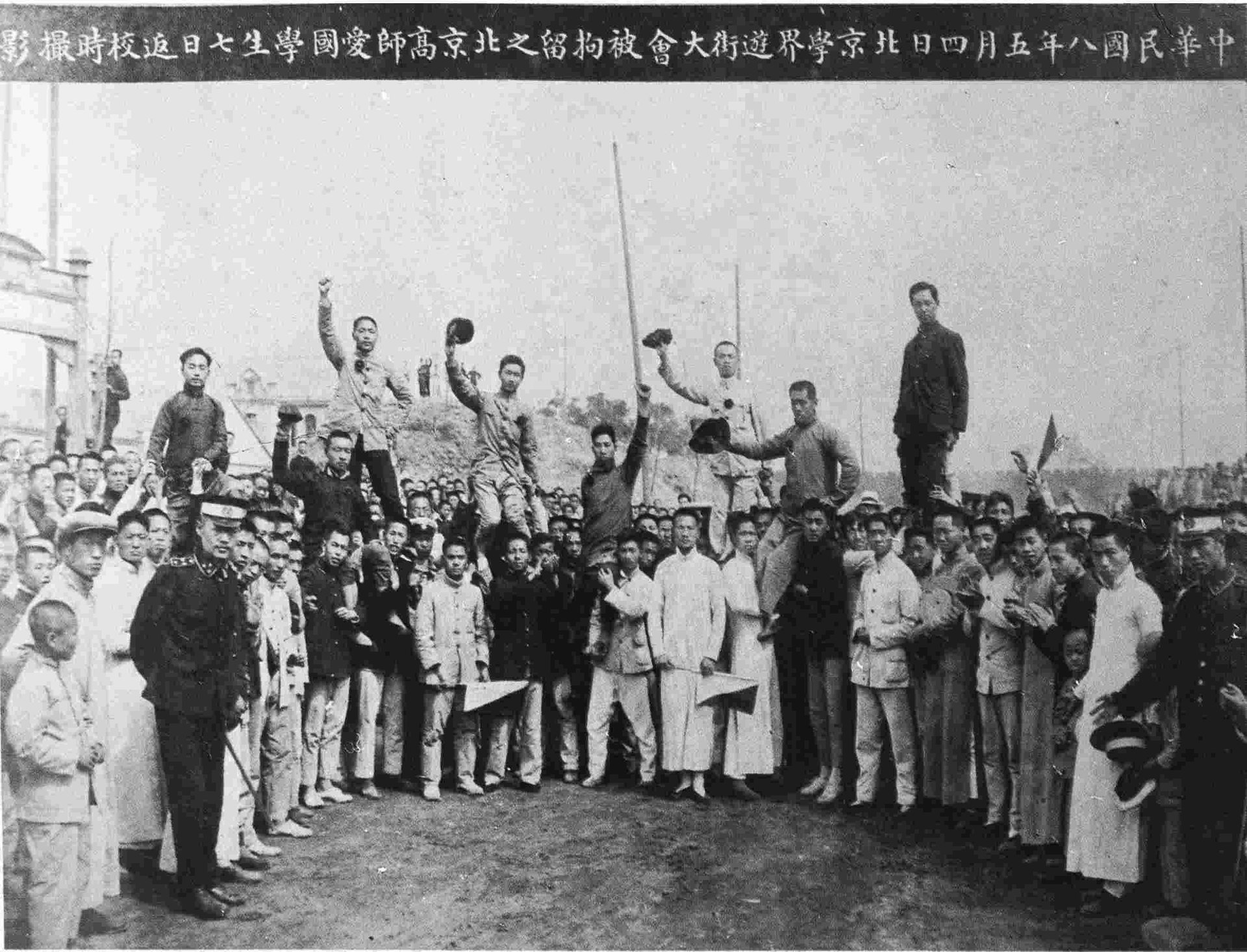

Angered by China’s inability to stand up against the Western powers, thousands of students protested in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. More than 3,000 students (link in Chinese) from a dozen schools in Beijing, including Peking University and Tsinghua University, joined the protest.

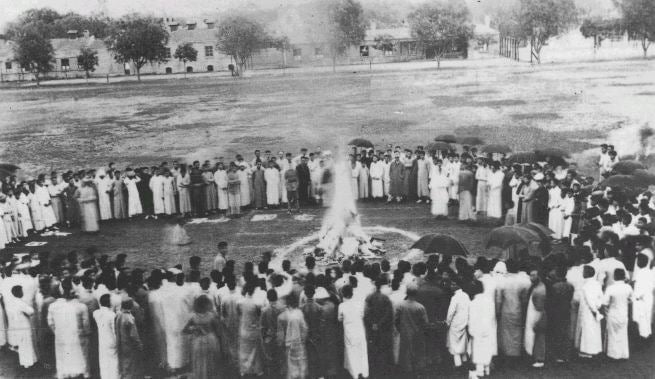

The students also accused their government of being spineless during the discussions that culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. Student protesters even burned down (link in Chinese) the house of Cao Rulin, a politician whom they blamed for bowing to Japan, and beat up Zhang Zongxiang, who was then the ambassador to Japan. Police later arrested 32 students (link in Chinese) near Cao’s house.

In May, more than 5,000 students from 16 schools in Beijing surrendered themselves (link in Chinese) to police in support of the 32 students who were arrested. Meanwhile, the protests spread to some 20 cities (link in Chinese) in the following months. In June, close to 70,000 workers in Shanghai went on strike in support of the students.

The government, facing public pressure, finally released the students. It also dismissed three officials (link in Chinese) whom the protesters deemed responsible for selling China out to foreign countries. China didn’t sign the Treaty of Versailles, but Japan retained control of the territory in Shandong for three more years until it agreed to return it to China during the Washington Naval Conference.

May 4 in Xi’s China

The May Fourth Movement inspired another important student demonstration seven decades later. On June 4, 1989, students from Beijing universities, and then later from schools across the country, took to the streets with a message that echoed that of 1919. In a key student manifesto, the protesters even dubbed their actions the “New May 4th Movement (paywall).”

The 1989 protests came at a time when China was gradually opening up to the world, but without any serious political reform. People were angry about endemic corruption and nepotism, while the death of a liberal reformist leader further invigorated the student protesters.

This time, authorities did not yield. The military launched a brutal military crackdown that killed thousands. Today, June 4 is one of the most politically sensitive dates in China, with anything remotely related to the event severely censored on China’s internet. Many young people do not even know that the crackdown happened.

The Communist Party’s zero-tolerance policy on student activism remains firmly in place today, though that hasn’t given the party pause in lauding the actions of the protesters 100 years ago. In fact, the event’s centenary is being proudly celebrated. Peking University, arguably ground zero of the May Fourth Movement, even organized a 5.4-kilometer run (link in Chinese) for 5,400 students and teachers to Beijing’s Old Summer Palace—one of the most potent reminders of China’s humiliating past when foreign powers freely plundered from its soil.

Today’s China is a far cry from the weak power that it was at the turn of the last century. As such, the party is able to play up the patriotic angle of the May Fourth Movement while eliding any mention of the protests’ anti-authority message. On Tuesday (April 30), Xi delivered an hour-long speech (link in Chinese) to a packed Great Hall of the People marking the 100th anniversary of the movement. Calling it a “great patriotic revolutionary movement,” he said that the party should listen to young people’s ideas, but also called on youth to love their country.

“Those who are unpatriotic, who would even go as far as to lie and betray the motherland, are a disgrace in their own country and the world,” Xi said.

Among those in the audience were hundreds of young people, who assiduously took notes as Xi orated. Some of those in the audience attend the very schools that sparked the May Fourth Movement in 1919. Yet most of them could never dream of protesting in the same way as students did a century ago, and will remember that their classmates who tried recently to stand up for causes such as labor rights or gender equality on campus did not succeed (paywall).