Right-wing “fake news” circulates on China’s WeChat app as Australia’s election nears

China’s social media app WeChat is in the spotlight ahead of Australia’s national election for allegedly spreading misleading information about candidates.

China’s social media app WeChat is in the spotlight ahead of Australia’s national election for allegedly spreading misleading information about candidates.

Australia’s opposition, the left-leaning Labor party, says it has identified articles on WeChat that spread fake news about the party, particularly on its immigration and education policies, several newspapers have reported. The country will vote on May 18 whether to keep the conservative Liberal party and prime minister Scott Morrison in power, or to take a chance on a Labor administration.

While WeChat is most widely used in China—where it has a billion registered accounts–it’s playing an increasing role outside China as well, where it’s not subject to (or at least not supposed to be subject to) the type of control that applies to its use on a China mobile number. Increasingly, the app is used in politics and civil-rights discussions in many countries. The app has been used to spread anti-government fake news in Canada, while Vassar professor Hua Hsu detailed (paywall) in the New Yorker last year how WeChat is being used in the US as a tool to organize opposition toward affirmative action policies at universities, which some argue is discriminatory against Asians.

In Australia, the app has also been a forum for support for more conservative policies.

In one popular WeChat post, an account from a self-identified member of the Liberal party, Jing (Jennifer) Li, posted a tweet that had been doctored to appear to be from Bill Shorten, leader of the Labor party, according to the Sydney Morning Herald. The post, which emerged on the weekend, said, “Immigration from the Middle East is the future Australia needs.”

Immigration is a contentious issue in Australia, where over the years migrants have tried to arrive by boat and seek asylum, leading to Australia’s policy of holding such applicants on offshore detention centers. These elections also come soon after deadly shootings at two New Zealand mosques by an Islamophobic Australian national. Morrison himself has campaigned around limiting immigration.

Li didn’t respond to queries from the newspaper.

Meanwhile, the Age newspaper reported that a scare campaign on WeChat claims that an effort by Labor to make schools more inclusive of LGBT students will teach children how to have same-sex relationships. Conservative ethnic Chinese were also vocal in campaigning against the legalization of same-sex marriage in Australia in 2017. Another WeChat post, meanwhile, said the party would seek more taxes from retirees who have a lot of investment income.

The Labor party said it has written to the app’s parent, social media and gaming giant Tencent, to flag the issue. Tencent didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment from Quartz. The governing Liberal party said it’s not affiliated with the misleading messages and can’t govern the comments of the app’s many users.

Monash University lecturer Wilfred Wang attributed the predominance of more conservative political and social views on WeChat to the fact that many Chinese migrants join churches to socialize and improve English, and also because a wave of business migration in the last decade brought the Chinese community closer to the pro-business Liberal party. “Naturally they learned about WeChat way earlier than their opponents, Labor,” said Wang, who studies the use of Chinese platforms like WeChat in Australia.

Fergus Ryan, an analyst at Canberra-based think tank Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), said that following an upset win for the Liberals in the seat of Chisholm in Victoria during the 2016 election that was widely seen to be the result of a WeChat campaign, May’s election “is probably the first election where both major parties have clearly seen the benefit of it as a channel and have directed more resources towards it and have increased their activity on it.”

Based on Australia’s official data, Ryan estimated that at least 20 federal electorates in Australia have voters of Chinese ancestry ranging from 9% to 21%, which makes them a “crucial demographic for political parties to target.

There are more than a million people of Chinese heritage in Australia, according to University of Technology Sydney media and cultural studies professor Wanning Sun, who estimated that about half of them speak Mandarin at home. Sun said that Chinese-language websites such as those operated by former Chinese migrant entrepreneurs who synthesize news from Chinese and Australian news outlets, accessed via WeChat, are a key source of information for many Chinese-Australians.

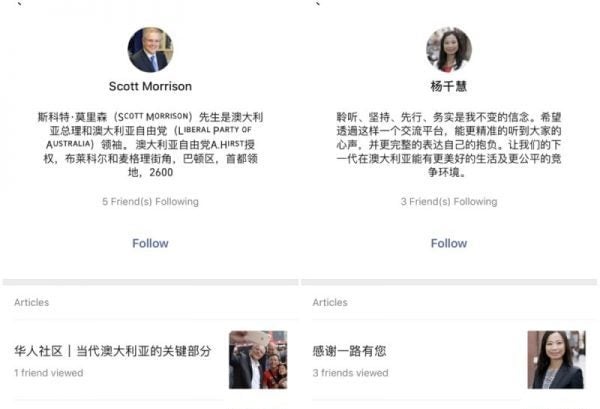

While posts from popular blogger accounts or closed group discussions can often gain the greatest traction, mainstream Australian politicians have nevertheless tried to reach out to Chinese-Australian voters. In February, prime minister Morrison joined WeChat, just in time to wish prospective voters a happy Lunar New Year.