Sneakers are not just shoes, they’re an asset class

Every day, more than $3 million worth of merchandise moves through StockX.com, an online reseller of luxury goods. About 75% of it is sneakers.

Every day, more than $3 million worth of merchandise moves through StockX.com, an online reseller of luxury goods. About 75% of it is sneakers.

The shoes, pre-owned but in new condition, trade hands between sellers and buyers who will pay hundreds, even thousands, for rare shoes. A pair of Jordan 1s from Nike’s recent collaboration with Travis Scott, for instance, routinely sells for more than $800, while in February, the average selling price of the Nike Mars Yard 2.0, created with artist Tom Sachs, broke the $3,000 mark. A flood of supply, meanwhile, can tank a shoe’s price, as happened with some other Jordan models when Nike increased their distribution, and with Adidas’s Yeezy Boost 350 in Cream after the brand did a wide release of the shoe in September.

The sneaker resale business is a niche compared to the primary market of brands and retailers selling to the public, estimated to be worth nearly $37 billion in North America alone according to market research provider Euromonitor. But that niche is still valuable, and growing fast. In April, investment firm Cowen sent a note to clients valuing the North American sneaker resale market at more than $2 billion and increasing at a double-digit percentage each year, with the potential to surpass $6 billion by 2025.

Much of the buying and selling happens in online marketplaces, and StockX says it’s the largest sneaker resale marketplace in the world, surpassing even eBay. In April, Recode reported that the company’s latest financing round values it at $1 billion, an unprecedented amount for a sneaker marketplace.

What makes StockX different than competitors isn’t just its size, but its ambition. The company bills itself as the world’s first “stock market of things.”

Prices on the site fluctuate constantly, based on the same model that underlies the stock market. Here’s how it works: Somebody who wants a shoe offers a bid. Somebody selling a shoe lists their ask. If the numbers meet, the transaction happens. A buyer can also purchase a shoe immediately for the lowest asking price, and a seller can sell immediately for the highest bid.

Like a stock exchange, StockX tracks prices and enables the trades, with the additional job of making sure every item it sells is genuine. Unlike eBay, StockX requires all sellers ship their goods to it for authentication before it ships them on to the buyers. If there are more buyers than sellers for a certain shoe, the price will trend up. If the reverse, the price will fall.

“This is Econ 101,” says Josh Luber, a sneakerhead, former IBM strategy consultant, and CEO of StockX. Luber launched the company in 2016 with Dan Gilbert, the billionaire founder of Quicken Loans and owner of the Cleveland Cavaliers basketball team, and Greg Schwartz, StockX’s COO, who worked with Gilbert at a venture investment firm. “All a stock market does is it basically quantifies supply and demand to create that true market price.”

Since the company launched with sneakers in 2016, it has kept branching out to other categories, including streetwear, watches, handbags, and soon collectibles. But sneakers are still its main trade.

When the company held an event it calls StockX Day in May, inviting about 300 people out of 9,000 applicants to come see its operations in Detroit, it was sneakers that most of the attendees were clearly interested in. (There were a few pairs of Mars Yards and Travis Scott Jordan 1s in the crowd.) It was a testament to StockX’s success, but also the value a pair of sneakers can hold today.

Sneakers are an asset class now

Cowen’s April research note carried a provocative title: “Sneakers as an alternative asset class.” In the note, the authors wrote: “We propose the idea that sneakers are now an emerging alternative asset class that 1) earns illiquidity premiums; 2) provides diversification—non-correlated with traditional asset classes; and 3) earns favorable risk reward characteristics.”

In short, sneakers are becoming an investment opportunity—one of the rare consumer goods whose value can actually increase over time.

Cowen’s point wasn’t that investors should run out and buy sneakers. It was that the secondary market—where resale companies such as StockX, GOAT, Stadium Goods, and Flight Club operate—is important for investors to pay attention to. In a video tied to the report, Cowen analyst John Kernan said “the resale market and the growing streetwear market, we think, presents a tremendous opportunity for many of these companies,” referring to the big sneaker players such as Nike, Adidas, and Puma. Resale also offers a valuable point of insight on the sneaker ecosystem—it can be a good indicator of a brand’s health, and how much people want what it’s selling.

In reality, it’s only a subset of sneakers that can provide a return. While brands such as Nike and Adidas do a lot of their sales on the sort of inexpensive casual shoes that sell in droves at chains such as Kohl’s, the resale market is based on more expensive, limited-release sneakers. Nike and its Jordan brand dominate the business, while Adidas, including its Yeezy line with rapper Kanye West, makes up most of the rest. Most shoes selling on StockX are reselling for between one and two times their retail price, according to a Cowen analysis, with only a subset earning higher premiums.

To get these shoes at stores or online when they are first released can be near impossible. When high-demand styles drop, most people walk away emptyhanded. Savvy resellers have developed bots that can quickly buy up the supply online, though brands and retailers have been working to combat them. The rush of traffic to a site can even crash it, producing lots of furious shoppers who can’t get through to purchase. For in-store releases, people may wait in line for several hours, even days.

It’s probably more than the average investor cares to undertake, but that limited supply is also what makes the shoes so valuable to resellers.

“When we say a ‘stock market of things,’ immediately everyone thinks about investments,” Luber says. “And rightfully so. That’s what people think about stock markets. In some regard that can be confusing or misleading, because it’s not about investments—or it’s not primarily about investments.”

StockX, he points out, is just a consumer goods marketplace, with a unique way of operating. Luber and Gilbert both got the idea for a marketplace with pricing based on a bid-ask model independently before they created StockX. At StockX Day, Gilbert joined Luber on stage and explained that the concept was something he had long wondered about. They’d even tested a bid-ask system for tickets at the Cavaliers. Gilbert, who has four sons and a daughter, noticed his sons always buying sneakers off eBay. “It just occurred to me and some others around us, how come there’s never been a ‘stock market of things?'” he said.

Thanks to the internet, they could build a marketplace for consumer goods with full price transparency, showing users what each item was selling for in real-time. Luber, in his spare time while at IBM, had built a site called Campless that scraped eBay for exactly that sort of data on sneaker sales. Gilbert and Schwartz reached out to him and convinced him to move from Philadelphia to Detroit.

Price transparency is only part of the equation though. The other piece they needed to work out was ensuring the authenticity of everything they sold.

How StockX authenticates sneakers

As with other valuable items, fakes are always a concern. Footwear accounts for more of the counterfeit items seized globally than any other product. According to statistics from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), of the $509 billion in fake goods captured in 2016—the most recent year with data available—22% was footwear. The OECD has previously identified Nike—not Louis Vuitton, Rolex, or Gucci—as the world’s most counterfeited brand. Compared to certain types of high-end goods and other products, a pair of sneakers is relatively easy to copy, easy to transport, and there’s a broad demand for the knock offs.

Not all the fakes are of rare Jordans or Yeezys. But there are enough that resellers have to be vigilant. StockX has four authentication centers: Three are in US cities, and one is in London. It also just announced a fifth center opening in the Netherlands.

On StockX Day, part of the event included a tour of its center in Detroit. Housed in a building stretching more than 20,000 square feet, the authentication floor looked like any warehouse floor, except piled high in spots with bright orange Nike boxes, black Jordan boxes, brown Yeezy boxes, and blue Adidas boxes. People were busy packing orders for shipment, and at well-lit stands, authenticators stood over streetwear and sneakers, inspecting every aspect of the merchandise. StockX’s sellers have to send their products to the company before the company ships them out to the buyer on the other end. To keep up, StockX employs more than 100 authenticators, and all undergo a 90-day training program to make sure they’re proficient at spotting problems.

It’s not just the shoe they look at. “The authentication process always begins with the box,” one of StockX’s sneaker experts told the tour group. They look at the color, the smoothness, the label, and check for any rips or tears. They verify that the labels on the outside list the correct size and style number. The details of the sale and the product are available on a computer screen at the station. If any problems appear, they contact the buyer.

On the shoes they examine the outsole, making certain there’s no wear. Fake shoes also have to use fake molds for their outsoles, so they’re a good indicator of a knock off. They verify the sizes, look at stitching and labels inside the shoes, and check for anything that even just feels off. That can include the way a shoe smells. If any issues arise, they contact the buyer.

StockX says just 0.1% of sneakers it has verified later turned out to be in error, whether because they were the wrong size, the box was damaged, the shoes had been worn, or because they were fake. A just-released pair of Air Jordan 1s made in collaboration with rapper Travis Scott was sitting at the authenticator’s station. At the time, they were reselling for about $900. When asked, nobody on the tour could tell if they were real or fake. It turned out they were fake. The giveaway was the box.

Luber says pretty much anything with a finite supply can theoretically work on StockX. But there’s a reason sneakers have done so well as a launching pad: They have a deeply passionate fanbase that wants to spend time researching, buying, and selling them, that will line up for days or spend $900 for the right pair. It’s not just about money. It’s about love.

The merger of resale and retail

Sneakerheads were once a niche subculture, but they’ve grown considerably as the internet has made it easier for people to swap information and buy and sell shoes. The rise of streetwear—a sneaker-centric style with roots in skate culture and hip-hop—has helped to fuel sneaker hype and demand.

Big companies now want a piece. Earlier this year, Foot Locker invested $100 million in the resale platform GOAT. At the end of 2018, Farfetch, an online luxury retailer, acquired resale platform Stadium Goods. Luxury conglomerate LVMH had bought a minority stake in the business earlier in the year.

Resale isn’t just growing in the US. It’s taking off in China as a passionate sneaker culture grows there. In May, SneakerCon, a popular sneaker convention, took place in Shanghai, marking its first time in mainland China. Some 20,000 people attended. For New York-based sneaker reseller Stadium Goods, the biggest shopping holiday of the year isn’t Black Friday, it’s Single’s Day in China.

Luber says China now accounts for about 10% of StockX’s business, without the company having any presence on the ground there. “We don’t have local language, we don’t have local payment methods,” he explains. “But they’re finding a way to be able to buy, because demand is so great.”

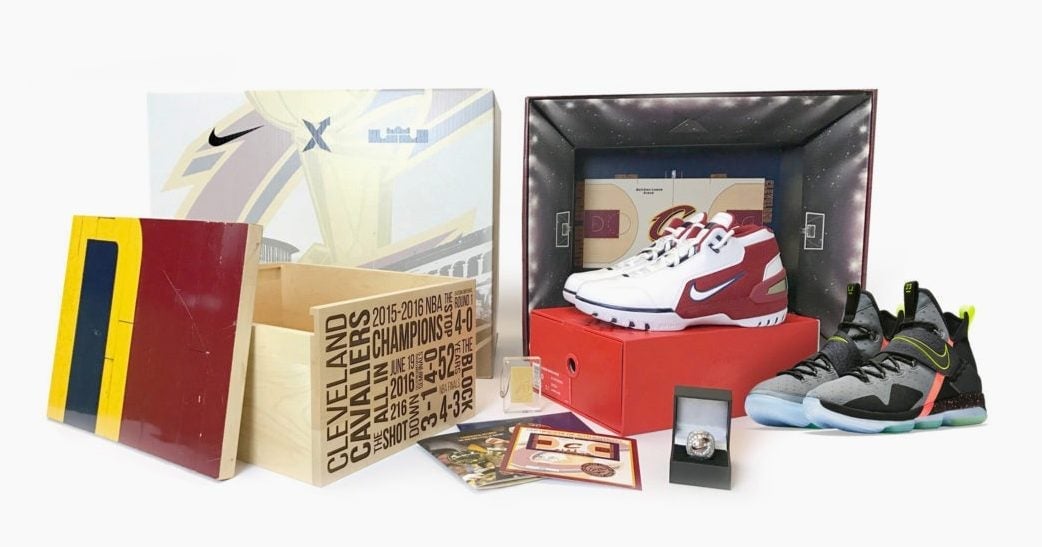

The next step, in his mind, is for the primary and secondary markets to start overlapping. StockX has already started down that path. In January 2017, Nike released a limited number of a new version of its LeBron 14, part of its signature line with NBA star LeBron James, directly on StockX before doing a wider release later. The shoes came in a wooden box made from the court the Cleveland Cavaliers—James’s team at the time—won the NBA championship on.

StockX has done more releases since. In January of this year, it held what it calls the first-ever e-commerce IPO, or initial product offering, for a slide sandal made with musician and jeweler Ben Baller.

Unlike in normal retail, the products launched in an IPO don’t have a fixed price tag. StockX wants the market to set the price, so it uses what’s called a blind Dutch auction: Customers place bids for the item in the size and color they want. The top bids matching the number of items StockX has in the size and color are winners, so if StockX has 20 pairs of the item in black and size 10, then the top 20 bids win. But the price everyone pays is the lowest winning bid. It’s called a clearing price, and ensures everyone is paying the same amount. It also means 19 of those 20 bidders will pay less than they actually bid.

“That’s really the future of this,” Luber says. He envisions more direct releases straight through StockX, and prices set not by the brands, but by the customers. People can even resell products before they’ve taken possession of them, like commodities traders.

It’s not clear how much of a role sneaker brands will want to play in that vision. Despite Nike releasing the LeBron shoe through StockX, the company has said it currently has no plans to work more closely with the resale market. “We’re fully aware that we’re a huge part of creating that market,” Andy Campion, Nike’s CFO, said on a company earnings call in March. “Right now we’re looking at it, but we have no plans in terms of partnerships or business strategy in that particular area.”

Brands may worry that the more people start buying on the secondary market, the fewer people who will buy straight from them or their retail partners. At StockX Day, Gilbert said in his experience with products such as mortgages, the opposite is true. “When a buyer of something knows that he can turn around and sell it into a liquid market, in the secondary market, they’re more apt to buy it in the first place,” he pointed out. He and Luber suggested that brands may eventually warm up to StockX the way sports warmed up to ticket resale and StubHub. In 2016, StubHub even started selling primary tickets—not just resale—for the Philadelphia 76ers basketball team.

In the meantime StockX and the resale market are growing fast, as demand for what they’re supplying only increases.