A month after a million people took to its streets to protest a controversial extradition bill, Hong Kong keeps being rocked by political strife.

Protesters and riot police tussled again Sunday night (July 7) after a march in the Kowloon area that was aimed at trying to explain Hong Kong’s cause to mainland Chinese tourists. That was a week after demonstrators took over the Legislative Council on the anniversary of the handover from British to Chinese control on July 1, 1997, under an agreement that Hong Kong was to preserve its freedoms for at least 50 years. The government on June 15 announced it would indefinitely suspend the extradition bill, which would have allowed criminal suspects to be transferred to China and was seen as a major threat to the city’s autonomy.

As the protests kept intensifying, chief executive Carrie Lam finally announced today (July 9) that the bill “is dead.” Even while admitting that the government’s attempts to push it through were “a total failure”, she again stopped short of withdrawing it. The discontent is likely to continue, deepened by a revival of deep-seated frustrations over the city’s lack of true political representation.

Where can Hong Kong go from here? One moment in its own history might offer a parallel.

How Britain handled the aftermath of the 1967 unrest

While the city is not new to mass demonstrations—the 2014 occupation of downtown Hong Kong to press for greater democracy, known as the Umbrella Movement, lasted 79 days—the only time the city saw serious street unrest was more than 50 years ago.

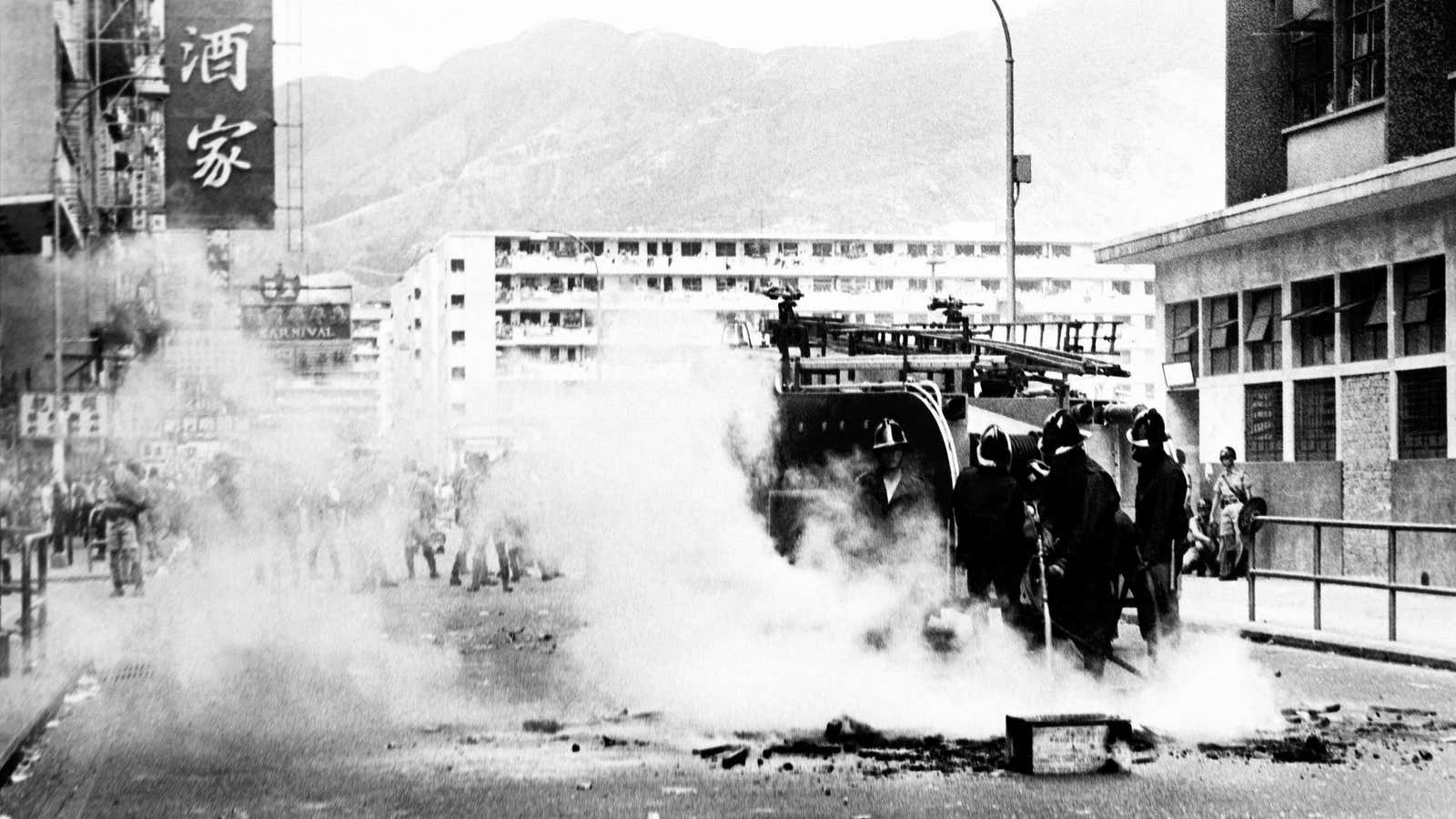

The 1967 riots fed on real local discontent, and were sparked by a labor dispute that year after workers were dismissed from a plastic-flower factory. But they were also a spillover of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution that had begun a year earlier—an internal party struggle aimed at stemming criticism of his failed economic policies dressed up as an attempt to purify Chinese communism of bourgeois influences. Mainland officials in Hong Kong and leftist students mobilized around the workers’ grievances. Soon these disparate forces snowballed into the biggest movement against the British colonial administration Hong Kong ever witnessed. A spate of bombings left 51 dead and hundreds injured, scarring the city and shaking the British administration.

The local branch of the Chinese news agency, Xinhua, coordinated many of the protest actions, and the old building of the Bank of China was covered in anti-British and pro Communist banners—until the central authorities in Beijing decided to rein in the rioters. The shock of those days, however, made the colonial authorities realize that Hong Kong was not as stable as they had thought, and they pursued significant changes to address grievances felt by many.

One reform was the opening of the District Council offices, which instituted a grassroots level of communication between government and people. Then, with the arrival of governor Murray MacLehose, Hong Kong saw other vital changes: among these, the use of Chinese (Cantonese) as one of the official languages; the creation of the Independent Commission Against Corruption; universal education and healthcare, and the beginning of a vast program of public housing. MacLehose also expanded public transport, with the opening of the Mass Transport Railway, or MTR, Hong Kong’s subway network. Many of the innovations brought after the 1967 riots are still in place today, and give Hong Kong part of its character.

Anna Wu Hung-yuk, a former Executive Council member, noted the importance of the District Councils, which she described as an effort to use administrative means to “tap the pulse of the public after the riots.”

“We need to go back to those major incidents and learn from the past,” she said. “Of course there are many differences, since this time the unrest is spontaneous, but it shows that Hong Kong society needs an honest broker, willing to negotiate the possibility of talks with the parties involved. The government must listen more.”

Looking for an “honest broker”

But it’s unclear who can be an “honest broker” given the level of distrust chief executive Lam now evokes, and the constant calls for her resignation despite a second apology for her missteps. An earlier invitation to some groups of students to come for private talks was rebuffed amid doubts this might be an effort to divide the movement. The public also mistrusts the local police watchdog body, seen as lacking teeth and independence—but Lam has remained steadfast in rejecting calls for an independent inquiry. Protesters also remain angry at police for labeling their actions that day a “riot,” which carries harsher punishment.

“This is a very tense situation, and I do not see any way out,” said Ma Ngok, a political scientist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. “…Lam has lost so much credibility, I don’t know if or how she can continue for the rest of her mandate.”

But Beijing has expressed its support for Lam—and if she steps down it could further reinvigorate the demand to allow universal suffrage in the selection of her successor, as an election would have to be held within six months to fill the position. Presently a committee of just 1,200 people chooses the city’s chief.

Given those constraints, perhaps the only way the government could extend an olive branch might be by shifting its stance on the police. It could follow in the steps of a British response to another set of riots, in 1981 in the London neighborhood of Brixton, home to many black citizens of Caribbean origin. Those erupted on April 11, 1981, after sustained confrontations with law enforcement, whom local residents accused of racism and violence. An investigation ordered by prime minister Margaret Thatcher and carried out by her home minister concluded that there was no “institutional racism” but put a large degree of responsibility for the unrest on the police, and was followed by changes to policing methods.

An independent process that assigns some blame and revises how police engage with Hong Kong’s people in future protests might be the closest thing possible to a good-faith gesture.

Hong Kong needs “a system where the protocols are clearer: what is the real definition of a riot? What is the protocol for using tear gas? It is essential, right now, to show to the public that accountability is taken seriously,” said Wu. “It is the only way forward.”

But like Ma, others too are doubtful that such efforts to show accountability will be forthcoming, given Lam’s unwavering support for the police so far. In any case, her ability to offer concessions to the protesters is circumscribed by what the central government will allow, political scientists say.

“So the question now is: does Beijing want to rule in a more heavy-handed way, or be more accommodating?” said Ma.

The latter seems unlikely, given Beijing’s tighter grip on the city since the 2014 protests. As just one example, Hong Kong prosecuted most of the leaders of those demonstrations. The mainland’s top office for Hong Kong affairs has already issued a statement saying it supports the criminal prosecution of protesters who stormed into the city’s legislature on July 1. And while support for the protesters remains high among the population, many in the city are bracing for a backlash, with arrests already underway.