In the more sober corridors of the Chinese bureaucracy, the watchword of 2013 was “deleveraging.” Slashing debt was one of the three big themes premier Li Keqiang emphasized throughout the year, inviting Barclays Capital to christen his policies “Likonomics.” Zhou Xiaochuan, head of the central bank, also beat that drum, calling for the market to “discover and correct” excessive lending.

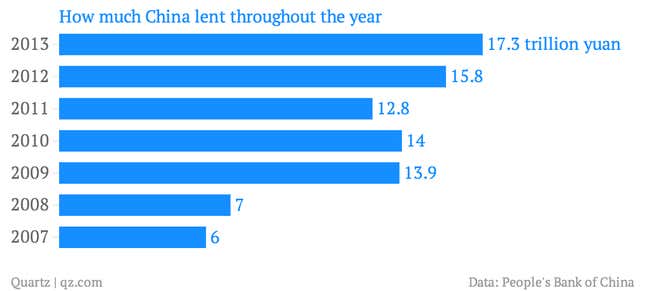

Well, that didn’t happen. Here’s a look at how 2013’s aggregate credit (link in Chinese) compares historically:

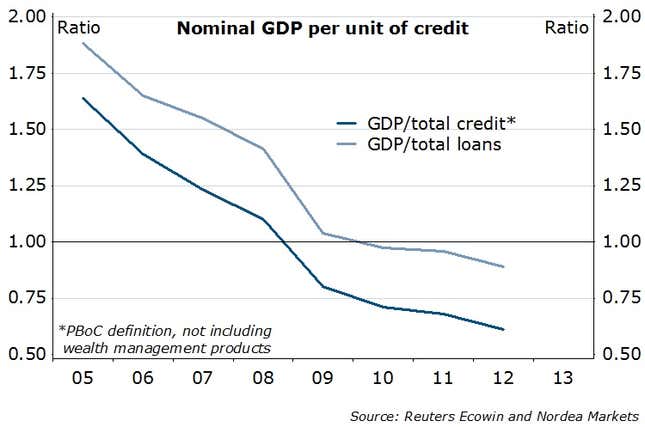

Even as total credit in China’s financial system hit a record high, return on that lending—meaning the value generated by those loans—”has declined to a very low level,” says Amy Yuan Zhuang of Nordea Bank.

There are a couple of reasons this is important. For one, it’s a reminder that even though the Chinese government is saying the right things about resolving its debt woes, something is preventing its leader from making that happen. What that something is—political clout? Vested interests?—is anyone’s guess. But it doesn’t bode well for reform.

A big reason lending surged in 2013 came down to shadow lending, the off-balance-sheet credit that typically goes to support businesses or local governments that wouldn’t otherwise qualify for loans. In 2012, shadow lending accounted for just 23% of total aggregate financing; last year, it surged to 30% (paywall). This type of lending is dangerous because it’s highly risky and it’s not clear whether banks, the government or retail investors will have to suffer any losses when loans go bad.

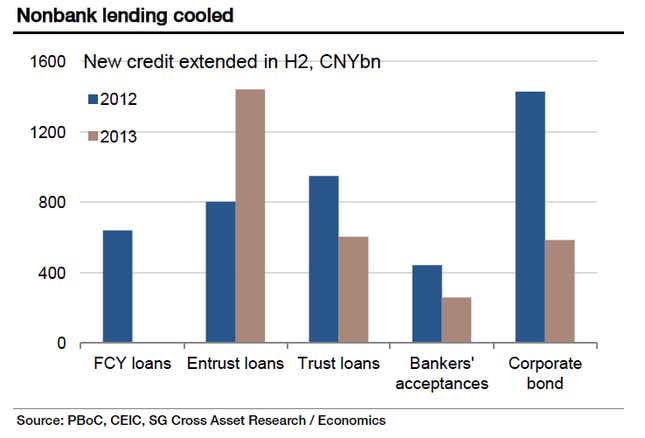

As you can see, some shadow lending—namely, trust loans and bankers’ acceptances—slowed somewhat in H2 2013. But entrusted loans, another shady credit instrument, sure didn’t. (Entrusted loans are loans between companies that use banks as an intermediary; trust loans refer to loans issued by trust companies, usually financed by wealth management products.)

And these are just the credit instruments that the government knows about. Banks and loan sharks have engineered plenty more financial “innovations” to take their place, which the government doesn’t yet track.

Still, reining in lending has had one crucial effect: It’s made many debt-saddled businesses increasingly hard-up for cash. That’s why any time liquidity stops flowing, lending rates spike, as they did in December and June of last year.

Even after these seizures subside, though, rates have stayed higher than before June 2013. That’s making China’s real businesses—the types far more likely to be eligible to issue corporate bonds—unable to get the credit they need. As Société Générale said in a note today, net corporate bond issuance hit a multi-year low of 24.2 billion yuan in December, making it “by far the biggest victim of tight liquidity conditions and relatively high market interest rates.” That’s a grim sign given that real businesses are the ones that drive real economic growth, which is what China needs now if it’s to avoid a debt crisis.