As branches close, tiny US community banks are sticking around

The number of bank branches in the US is on the decline. Thanks to community banks, however, places with relatively small populations have been able to buck the trend and hold onto their local bank.

The number of bank branches in the US is on the decline. Thanks to community banks, however, places with relatively small populations have been able to buck the trend and hold onto their local bank.

Only 3% of the banks in counties which had just one branch in June 2010 had closed up shop as of June 2019, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) data compiled by Quartz. In contrast, counties with 20 or more full-service branches in 2010 have lost more than 10% of their banks. In short, lenders are probably pruning branch networks in places where there’s the most competition, or where greater overlap makes multiple storefronts redundant.

Banks are closing physical branches as more personal finance activity moves online. A growing number of consumers would rather open an account or check their balances on their phones than visit a traditional teller. Community banks in rural areas must also contend with shrinking populations. Venture capital has flowed into next-generation fintech firms (Quartz member exclusive) that offer slick apps and no branches.

But not everyone is ready, or wants, to do all of their banking on a smartphone. The elderly and some vulnerable groups aren’t always comfortable using mobile phone apps, and bank branches can help preserve their ability to live independently. The poor and lower-income consumers are also more likely to rely on cash, which requires offline bank infrastructure.

Many people still prefer face-to-face conversations with bankers when loans and larger sums of money are on the line. Research in the UK has shown that small businesses are more likely to seek the financing they need to grow if there’s a bank branch nearby.

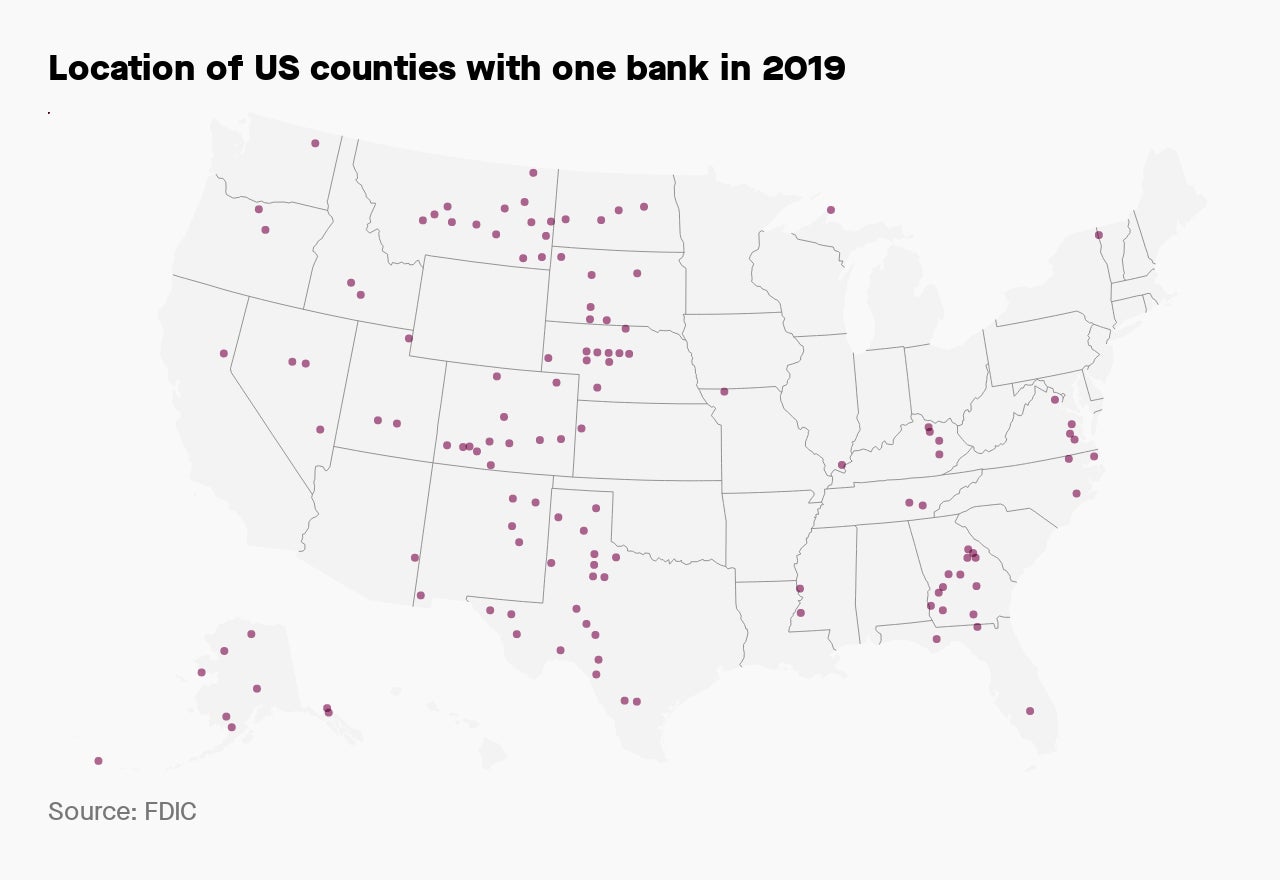

American community banks appear to be well anchored in the places that need them most. All 174 US counties with only one bank branch are served by banks with less than $2 billion in assets, suggesting that the vast majority are community banks.

These small lenders are sometimes started by businesspeople who live there, or may be handed down within a family, which means they aren’t subject to the whims of a parent company headquartered many miles away. They are also likely to be well known in their area and to have deep local relationships, according to the FDIC. Their name recognition and history can mean they essentially have a lock on the local market.

Take Spur Security Bank, a lender located about 70 miles from Lubbock, Texas, that received its banking charter in 1909. Elaine Key has worked there for 38 years and says it has always been the only bank in the county, as far as she knows. She said the company’s deep roots in the community help it make better credit decisions.

Key said the number of customers using the bank is stable, though it’s declining slightly along with the county’s shrinking rural population. Spur, where the bank is located, is in Dickens county, where the population has declined about 35% since 1980, to around 2,200 people.

“The majority of our customers are very loyal,” she said in a telephone interview. “As time has gone by, it’s easy to bank anywhere. Technology has made that possible. Our customers like to be able to come in and they like to be able to call and talk to a person.”

Community banking on the whole appears healthy, according to the FDIC, with loan and asset growth that can exceed larger, national lenders. Things could get bumpier in the future, however. Small-business lending platforms like Kabbage and Square Capital are gunning for some of the same customers served by community banks. These platforms’ credit algorithms can process applications almost immediately, and borrowers can get their money just about as quickly. Some research has signaled that credit algorithms can also be more color-blind and less discriminatory than traditional loan officers.

For now, however, US community banks appear to be weathering changes in the digital economy just fine.