None of the raft of horrible China data that came out today was terribly surprising. The Chinese New Year holiday always distorts January and February activity. Plus, rising steel inventories of late have augured a manufacturing slowdown, as has fizzling growth in the property market.

But February’s sharp drops in investment, industrial output and retail sales are still alarming enough that the normally upbeat Ting Lu, an economist at Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, slashed his growth estimate for 2014 to 7.2%, down from 7.5%. “Markets have been quite negative on the Chinese economy in the past months, and will likely respond negatively to today’s weak data,” he wrote in a note earlier today.

More than Lu or markets, it’s China’s leaders who will need to brace themselves. Much lower growth is the inevitable cost of implementing crucial market reforms, as the government is well aware.

The unexpected slowdown happening now is a big test of the government’s resolve. If leaders buckle under the pressure to keep growth in 7% or even 6% range, they increase the risk of a financial crisis or a decade or so of “Japanese-style deflation.” They’ll also prevent China from “rebalancing” its economy so that household consumption drives growth instead of investment—a vital prerequisite for China to emerge as a source of global demand and, therefore, an engine of global growth.

Promisingly, there are signs that China’s leaders are cool with letting growth slow. Earlier today, Li Keqiang, China’s premier, said that the government would carry out market reforms—which are likely to curb growth—”without hesitation.”

“What we care more about is the livelihood of our people,” Li said. “The GDP growth we want brings real benefits to our people, helps raise the quality and efficiency of economic development and contributes to energy conservation and environmental protection.”

There’s reason for skepticism, though. After all, these are the folks who only last week set their GDP growth target for 2014 at 7.5%, even as they proclaimed their commitment to sweeping reforms that will make that extremely difficult to pull off.

Another reason for doubt comes from the central bank’s cheapening of the yuan of late. Not only has that helped make Chinese manufacturers more globally competitive, but it has also kept liquidity loose, as we explained yesterday.

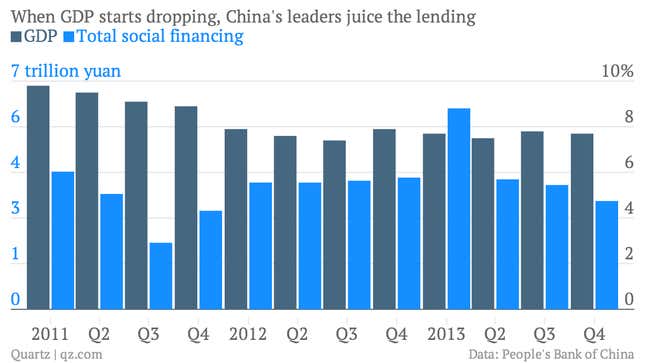

It’s hard to tell what’s happening with credit right now; while total social financing was unexpectedly high in January, it also came in unusually low in February. March financing data will be important to watch, considering China’s track record.

And that’s an important point. China has been threatened with a slowing economy before. But in the past, when growth has started to drop, the government has opened the lending valves.

Wei Yao, a economist at Société Générale, sees China’s new leaders—Li and president Xi Jinping—as “less pro-growth” than the previous administration. She worries, however, that the just-above-7% growth that now seems likely “is probably still more than what they can stomach.” Let’s hope she’s wrong. If it continues with that pattern, it will get harder and harder to implement those much-discussed reforms.