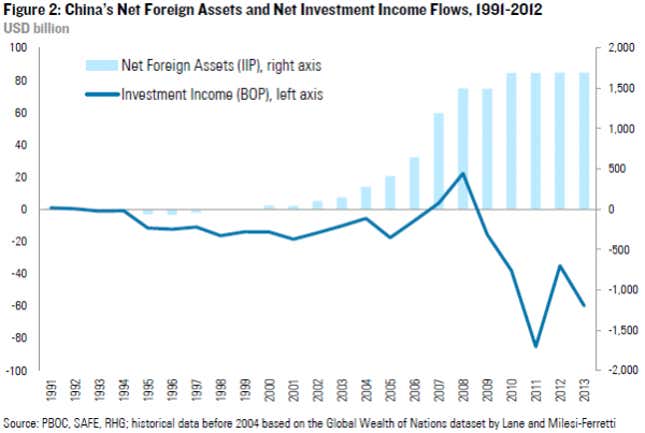

After Japan, China is the world’s largest investor. It also might be the one that gets the lowest returns. Last year, China’s global assets—both the government’s and those of private investors—rose to $5.9 trillion, a 14% increase on 2012. That’s $1.97 trillion more than foreigners invested in China. However, these investments yielded a paltry $168 billion in net investment income that year, as Rhodium Group’s Thilo Hanemann flags.

That’s a roughly a 2.8% annual dividend on one of the world’s largest chunks of invested capital. Investors in China have gotten juicier returns, raking in an annual 6%-8% in investment income. And that’s why China ends up paying out more in investment income than it takes in—shelling out $60 billion more to foreigners than it reaped on its own overseas assets.

Why are China’s investment returns so, well, meh? China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), holds than two-thirds of the country’s foreign assets. The trouble is that low-yielding US government debt is pretty much the only market big and liquid enough in which it makes to invest such a large sum.

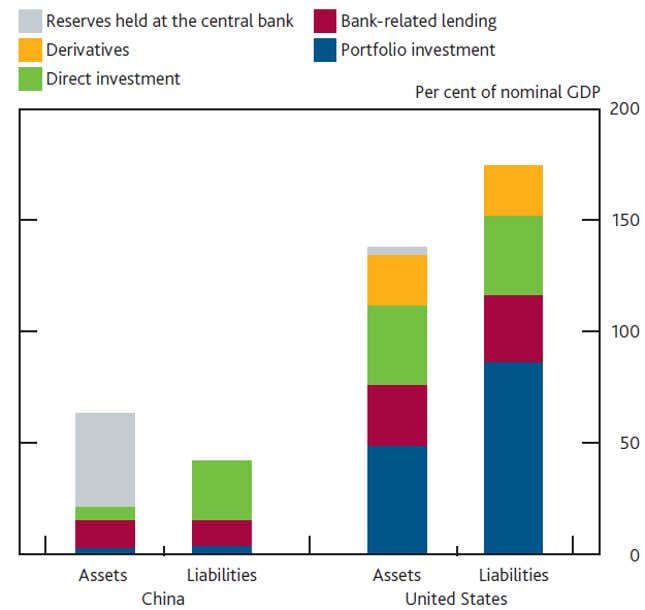

In this, China is unusual; most other countries’ central banks invest far less than companies and households. For example, China’s outbound portfolio investment—i.e. stocks, bonds and other securities—is just 3% of its nominal GDP, compared with the US’s 47% (pdf, p.306). As for foreign direct investment (FDI), inbound and outbound investment in the US make up roughly the same proportion of its GDP—a little more than 30%. But while inbound FDI equals about a quarter of China’s GDP, outbound investment is less than 10%:

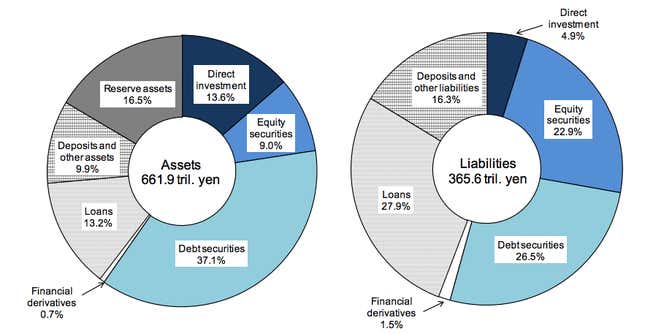

Japan is much more similar to China in economic structure, and yet it too has a much more diverse array of inbound and outbound investment. For example, Japanese companies and households held a little more than $3 trillion in foreign securities (pdf, p.6), as of the end of 2012—more than 50% of Japan’s GDP.

Investing in foreign companies or stocks at least has the potential to yield more than US Treasurys. So why does the PBOC hog all China’s foreign currency and sink it in low-yielding bonds?

That’s the price of centrally planning your economy. China’s ”closed capital account” means the PBOC tightly controls who can move money in and out of the country, making it very hard for households and smaller, non-state companies to invest their money outside of China.

And by controlling capital flows, the PBOC helps Chinese exporters, keeping the yuan cheaper than it should be (here’s more on how that works). Basically, every time China exports more than it imports, or attracts foreign direct investment, the PBOC forks over extra yuan for dollars. This allows the government to rig the banking system to hit GDP targets and fund its own policy objectives, with state-owned banks loaning to state-owned enterprises. And the central bank does that cheaply by keeping the deposit rates excruciatingly low, both forcing households and private companies to subsidize loans to state companies, and making them save more than they otherwise would.

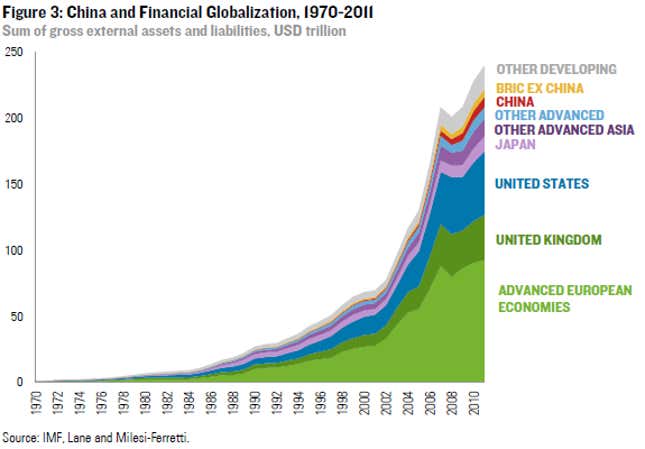

This closed system is why China generates only 3% of cross-border assets and liabilities, despite accounting for 12% of the world’s GDP. As you can see in the chart below, that’s tiny relative to other leading economies.

Rhodium’s Hanemann notes that the government’s already tinkering with loosening FDI rules—a promising step in allowing freer capital flows. But the increase that results will be small potatoes compared to what will happen when China finally opens up its capital account, as its leaders have vowed to do in the course of the next decade. When that finally changes, watch that red swath get way, way bigger.