Can Farfetch own online luxury?

If you spend any time shopping for high-end fashion online, you may have already bought something from Farfetch, which bills itself as the world’s largest digital marketplace for luxury. The site carries clothes from a huge library of labels—more than 3,500, it says—including big names like Gucci, Prada, and Saint Laurent, and niche designers like Budapest-based Nanushka.

If you spend any time shopping for high-end fashion online, you may have already bought something from Farfetch, which bills itself as the world’s largest digital marketplace for luxury. The site carries clothes from a huge library of labels—more than 3,500, it says—including big names like Gucci, Prada, and Saint Laurent, and niche designers like Budapest-based Nanushka.

Vast as that marketplace is, it represents just one piece of Farfetch’s ambition. As founder and CEO José Neves put it to analysts during an earnings call in February, the company’s goal is to be “an operating system and digital enabler for the entire global luxury industry.”

What is Farfetch?

Neves, a Portuguese entrepreneur, launched Farfetch in 2008 as a way for small fashion boutiques around the world to put their wares online without having to build and maintain e-commerce sites of their own. Farfetch’s value prop was that it would do the work for them: A little boutique in Antwerp might buy items from a designer brand, and then Farfetch would photograph the clothes and list them on its marketplace. When a sale happened, the store shipped directly to the customer and Farfetch collected a commission, avoiding the risks of carrying inventory itself. The concept worked, nabbing Farfetch a $1 billion valuation by 2015.

Since then, the company has set its sights on ever-grander goals: not just selling more goods to global shoppers, but adding businesses to its portfolio, providing more services to fashion companies, and working directly with major brands. Farfetch now offers what it calls Farfetch Platform Solutions (FPS), a suite of products that enable companies to run their own brand websites, iOS apps, and even stores on WeChat, China’s huge messaging network, using Farfetch’s infrastructure. It provides in-store technology, too, including tracking what a shopper picks up.

“The brands have for generations really focused on bringing customers into either their own fabulous boutiques, the multi-brand retailers and boutiques that exist within the industry, or the department stores,” says Elliot Jordan, Farfetch’s CFO. “They’ve never really adopted a view of being able to sell products online, or being able to connect the industry together through some sort of platform technology to be able to meet the needs of a tech-savvy customer.”

Currently FPS accounts for less than 10% of merchandise sales through Farfetch, according to Jordan, but he believes it will grow substantially in the years ahead. Companies using FPS or Farfetch’s in-store products already include Chanel, Burberry, Zegna, and Harrods department store. More than 570 brands, including the aforementioned Gucci and Prada, now sell directly on Farfetch via an e-concession model where they—not other retailers—list and control the items for sale.

Meanwhile, over the past several years Farfetch acquired Browns, a well-known London boutique; Stadium Goods, a sneaker resale marketplace; and New Guards Group, a specialist in launching and developing new fashion brands (hence Farfetch’s interest), which is also the exclusive license holder for popular streetwear labels like Off-White and Ambush.

These varied pursuits and, until just recently, Farfetch’s lack of profitability, have sometimes flummoxed investors since the company’s IPO in 2018. But Farfetch continues to grow and lure partners into its corner. Last year, it announced a deal with Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce giant, and Richemont, the Swiss luxury group, to put Farfetch’s fashion on Alibaba’s Tmall and “accelerate the digitization of the global luxury industry.” As part of the deal, Artémis, the holding company controlled by François-Henri Pinault, CEO of the luxury group Kering, increased its investment in Farfetch.

Jordan describes it as a group focused on stitching together all the different touchpoints consumers encounter across luxury, both online and off, into one seamless experience.

Farfetch revenue and other figures

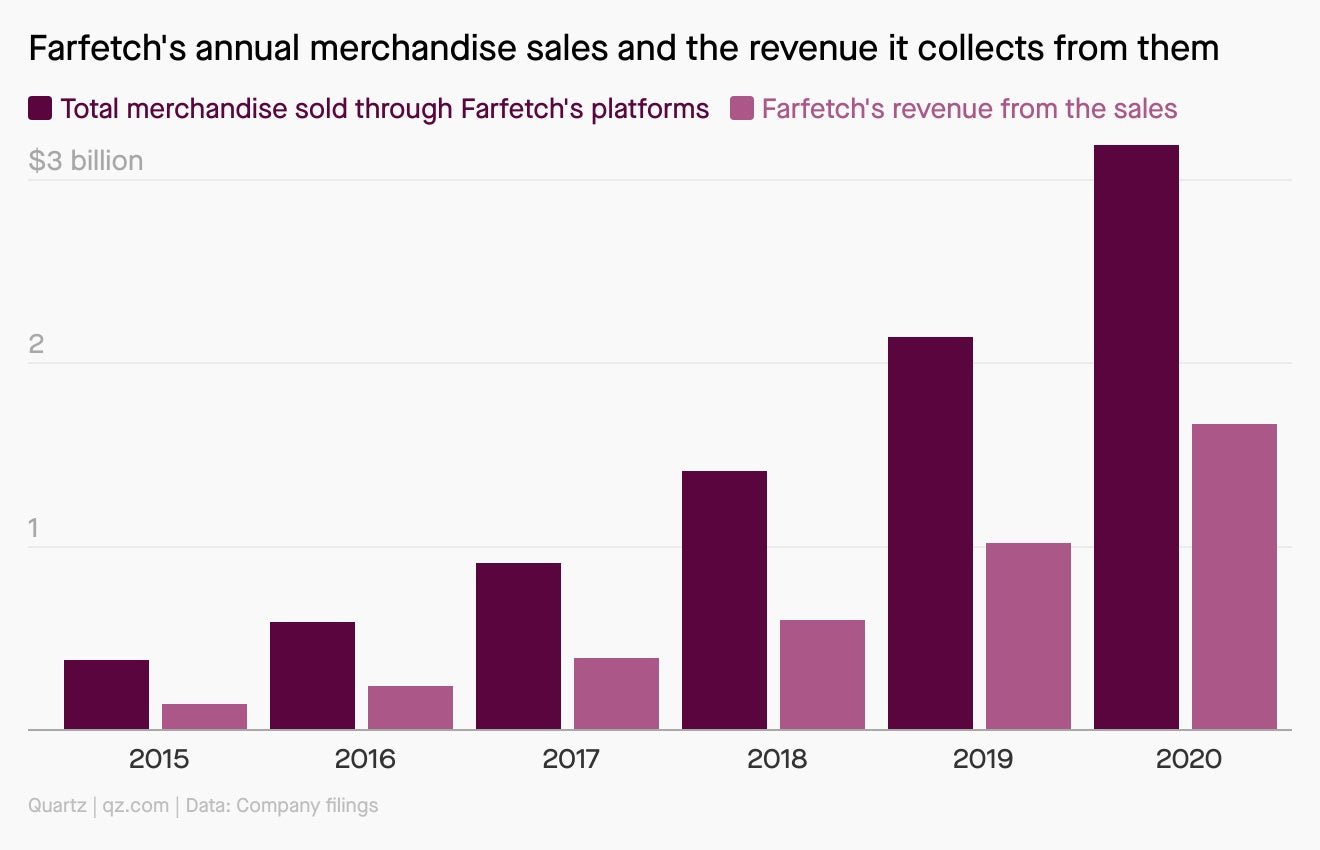

$3.2 billion: Total value of merchandise sold on Farfetch’s platforms in 2020.

$1.7 billion: Farfetch’s revenue from those sales.

$3.3 billion: Farfetch’s loss after tax in 2020.

3.3 million: Customers who made a purchase on one of Farfetch’s platforms in the 12 months through March 31.

$618: Value of the average customer order on Farfetch in the first quarter of 2021.

190: Countries and territories Farfetch serves.

$11.30: Farfetch’s share price on Jan. 3, 2020.

$49.76: Farfetch’s closing price on July 7, 2021.

Farfetch’s sales keep gaining altitude

Farfetch merchandise sales—and the company’s revenue from those sales—have been climbing since its IPO in 2018. Even the pandemic buoyed Farfetch, as it drove more luxury sales online.

Farfetch’s competitors

Farfetch has a number of competitors in digital luxury, including more traditional retailers such as the Yoox Net-a-Porter Group. But one major challenge the company faces comes from the increasing control major fashion brands are exerting over their own sales.

While luxury has historically relied heavily on a wholesale model, more companies are focusing on selling directly to shoppers through their stores and e-commerce sites—what insider types call “brand.com.” This way they get to control their entire relationship with the customer and don’t hand power to any one gatekeeper—plus the margins are better. Shoppers, meanwhile, connect directly with the brand and don’t have to worry about issues like fakes.

The multi-brand retail model isn’t set to disappear anytime soon though. Boston Consulting Group estimates multi-brand platforms will grow their share of luxury sales from about 6% in 2019 to approximately 14% by 2023. Brand.com, meanwhile, will account for 11% of luxury sales by 2023, up from 5% in 2019, it said.

Farfetch, meanwhile, is hedging its bets by letting brands sell directly on its platform. Jordan says the arrangement allows Farfetch to offer a much deeper selection of products from those brands, too. A retailer might only buy a handful of styles from any one brand, so it only has that handful to list on Farfetch. But the brand itself has the ability to make every style it has available if it chooses.

How Farfetch revenue breaks down

Most of Farfetch’s revenue still comes from the commissions and fees it collects from sellers on its marketplace, but that’s just one way it makes money at this point. Here’s a look at its business in 2020:

Luxury fashion’s digital future

Though luxury fashion was slow to embrace e-commerce, shoppers moving online left luxury sellers with little choice but to follow. The pandemic accelerated that shift. By 2025, online sales of personal luxury goods are projected to reach as high as €115 billion ($136 billion), up from €33 billion in 2019, according to a report by Bain & Company, a management consultancy, in association with Altagamma, an organization of Italian luxury companies. That means nearly a third of personal luxury sales will take place digitally, according to the projection.

Does Farfetch sell fakes?

Farfetch expects the products on its marketplace come from licensed retailers or sometimes the brands themselves, but in regulatory filings it has acknowledged the risks of counterfeit goods creeping onto its site. “While we have invested heavily in our authentication processes and we reject any merchandise we believe to be counterfeit, we cannot be certain that we will identify every counterfeit item delivered or returned to us,” it said in a recent filing (pdf) with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. It’s a challenge any company running a marketplace has to contend with.

Keep learning:

- Why is everyone betting on Farfetch (Business of Fashion)

- Is the New Guards Group the New Guard of Fashion? (New York Times)

- How Farfetch prospered in a pandemic year (Financial Times)

- José Neves on Building Farfetch (YouTube)

- Farfetch’s August 2018 S-1 filing, ahead of its IPO (SEC.gov)