Across global Wall Street, the once-mighty bond-trading business is shrinking. Facing regulatory scrutiny, banks have jettisoned formerly profitable commodities trading businesses. And the beating heart of the banking business—investment banking—has been, basically, pronounced dead, by none other than Morgan Stanley’s chief executive James Gorman.

Except, that is, at Goldman Sachs.

In recent months, Goldman has effectively outlined a strategy that zigs, while the rest of the financial world zags. The bank, led by CEO and chairman Lloyd Blankfein, has:

- stated that it is staying put in commodities trading as others are exiting

- called out investment banking as one of the keys to its success

- committed to bond-trading business best known as fixed income currencies and commodities, or FICC (paywall).

Taken as a whole, Goldman’s refusal to part with key activities reflects Blankfein’s deep skepticism that the business of large financial institutions has been as fundamentally altered as some think. Goldman Sachs is willing to bet that some of those businesses will be back. If and when they do rebound, Blankfein clearly states, Goldman will be ready.

“I’ve just been doing this a long time. I’ve been doing this over 30 years,” the Goldman Sachs CEO told Quartz in an interview after the firm’s annual shareholder meeting in Dallas, Texas on May 16. “I think it’s a vanity to say something that has worked is not going to work from this moment forward.”

Indeed, these businesses never really stopped being profitable altogether. For example, Morgan Stanley recorded a year-over-year revenue increase in its FICC trading driven largely by its commodities trading. Yet Morgan is selling a large chunk of its commodities trading operation to Russian oil giant Rosneft. (Banks are opting to jettison commodities trading as regulators (paywall), principally the US Federal Reserve, are scrutinizing activities in that area.)

Banks including Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase, Barclays also have offloaded, or scaled back, their own commodities operations. Barclays‘s moves are a part of a larger downsizing of its investment-banking operations. These firms are shedding businesses like commodities and dialing down investment banking, where firms put their money at risk, mainly because they are more expensive to operate under toughened regulations requiring banks to put up more of their own money to support risky assets.

Blankfein instead focuses less on structural changes to the industry, and more of the short-term cyclical trends—such as the lack of market volatility that has been weighing on results. Volatility (the up-and-down daily movement of the values of equity and debt securities) has been fairly flat in recent quarters. Traditionally higher volatility suggests higher trading activity in stocks and bonds, which can mean higher revenues for firms.

“I think it would be a risk with our shareholder’s franchise if we had built big franchises over decades and let them go because the markets haven’t been volatile for the last few quarters,” Blankfein told Quartz.

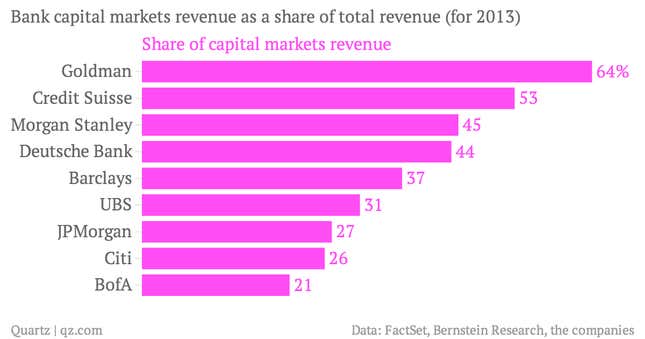

Goldman may have little choice in its decision to continue to maintain its investment banking and trading businesses. It doesn’t have a retail presence in the same ways as banks like JPMorgan Chase. And unlike Morgan Stanley it has opted not to dig deeper into wealth management. Those activities offer steadier, albeit potentially more modest, returns than the business of trading. Capital markets activity (trading of products like stocks and bonds) comprised 64% of Goldman’s total revenue in 2013. Other firms are far less dependent on capital markets to drive revenues.

“In the case of Goldman Sachs, the question is how do you survive the change of the economics of the business?” said Sanford Bernstein bank analyst Brad Hintz. “They are too large to shut their equities and fixed income down, it’s too large of a business for Goldman,” he noted.

Blankfein scoffed at the notion that the firm was stubbornly holding onto the flagging businesses that are facing serious changes. He noted that the company has been buoying its bottom line by cutting billions of dollars in costs through more use of technology. Goldman has also been staffing up in locations like Dallas, Texas and Salt Lake City, Utah, and Malaysia where the expense of operating and hiring top employees is cheaper.

Blankfein suggests that his willingness to hold onto some business lines other banks have done away with isn’t an all-or-nothing bet that Wall Street will return to the way things were before the crisis. Nor is he saying that volatility will definitely return to the markets very soon to beef up trading results. He frames the decision less as prediction, and more as contingency planning.

“We’re dealing with the world as it is,” Blankfein said. ”But I will tell you we’re also not throwing the baby out with the bathwater. And if things change, you’ll wonder how we were nimble.”