Riots, a missing plane, and a coup are wrecking Southeast Asia’s tourism sector

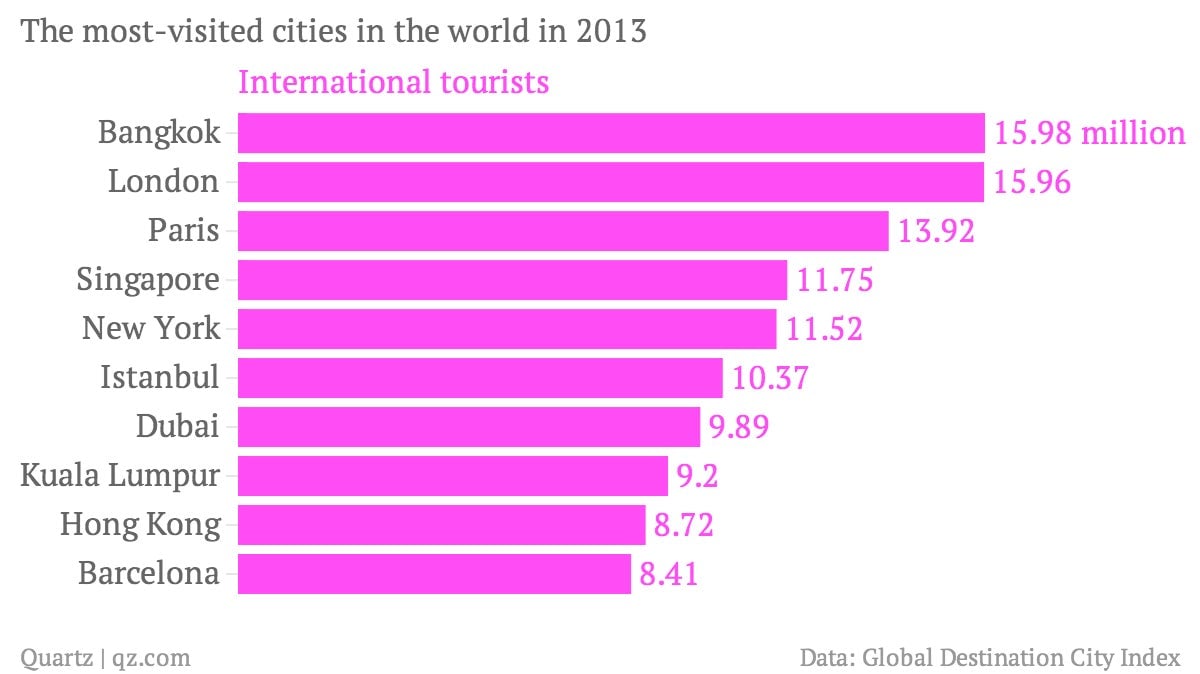

The past few years have been booming for tourism in southeast Asia. Newly affluent tourists from China, India and the rest of Asia, the growth of low-cost airlines and Middle Eastern carriers in the region, and improving infrastructure and tourism facilities have brought record-breaking numbers of tourists to Thailand, doubled the number of international visitors to Vietnam and in total pumped nearly $300 billion into the region in 2013.

The past few years have been booming for tourism in southeast Asia. Newly affluent tourists from China, India and the rest of Asia, the growth of low-cost airlines and Middle Eastern carriers in the region, and improving infrastructure and tourism facilities have brought record-breaking numbers of tourists to Thailand, doubled the number of international visitors to Vietnam and in total pumped nearly $300 billion into the region in 2013.

But now an unforeseen combination of political upheaval in Thailand, a transportation tragedy in Malaysia and Vietnam’s violent protests against mainland Chinese that make up the bulk of the region’s visitors are dampening the region’s tourism boom.

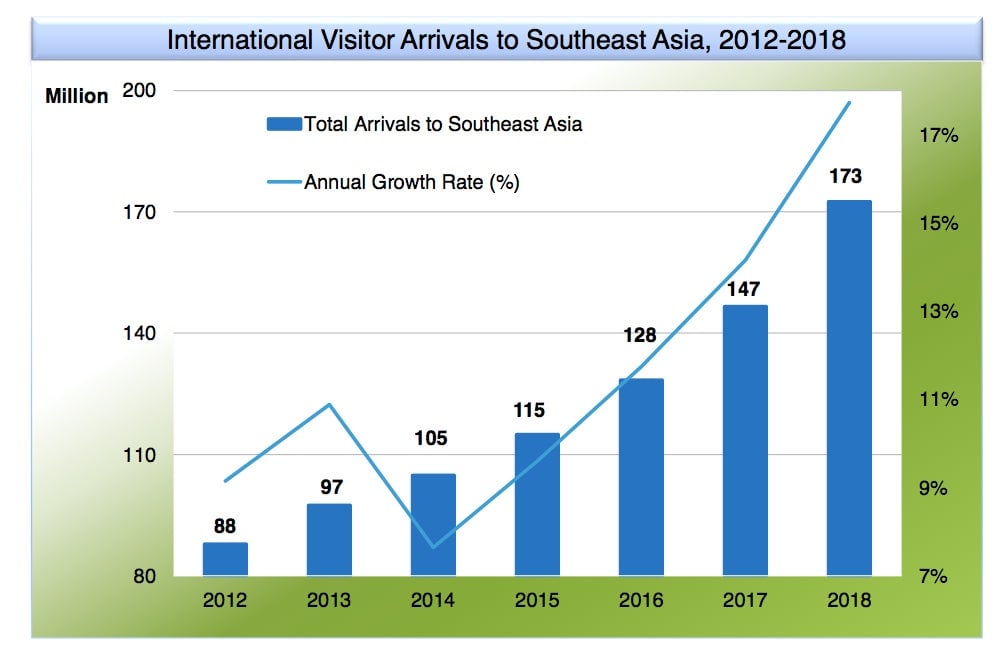

International visitors to Southeast Asia increased nearly 20% between 2008 and 2014, according to the Pacific Asia Travel Association:

In Thailand, months of political unrest was capped today with the military declaring martial law, creating more uncertainly for the tourism industry. “The Thai tourism industry should remain strong—if there’s no violence,” Nomura analyst Wassachon Udomsilpa told Quartz. The political incidents that had the biggest impact on tourism in recent years were violent clashes between protestors and police in Bangkok in 2008 and 2010, he said.

Any drop in tourism could severely impact rosy projections for international hotel chains, airlines, and regional GDP.

Earlier this year, analysts predicted the spillover effects from Thailand’s political unrest would help nearby tourism destinations, particularly Malaysia. But the Malaysia Airline passenger jet that disappeared in March, and the messy aftermath of the search for the plane, has deterred Chinese tourists. The still-unresolved kidnapping of a Chinese tourist in a Malaysian dive resort weeks after the plane went missing hasn’t helped matters—Malaysia had lost 105 million ringgit ($32 million) because of trip cancellations by the end of April.

And last week’s riots in Vietnam, where Chinese tourists were the leading international visitors to the country last year, have already sparked a wave of cancellations.

The combined impact on the region’s economy could be massive. The influx of tourists, heavily from China, has helped grow tourism and trade to 12.3% of South East Asia’s GDP in 2013, or $294 billi0n, the World Travel & Tourism Council estimates:

What’s even more important, though, is the tourism industry’s contribution to total employment, a key factor in political stability in the region. Travel and tourism created more than 28.6 million jobs in 2013, directly and indirectly, the World Travel & Tourism Council estimates. Based on bullish projections of more than 5% growth a year total spending from tourism, that number is expected to rise to 37.8 million by 2024:

It is hard to predict right now whether the combination of riots and coups, tragic accidents, and kidnappings will have a long-term impact. Analysts, including those at Nomura, say they remain confident about tourism in the region.

But the outlook still seems less optimistic than just a few months ago, when investor Marc Faber predicted in Barron’s that “Tourism in Asia will grow, unless there is a war.” Right now, while there’s no war, the region’s tourism hotspots are facing nearly everything else.