China’s years of stimulating its economy have left it more indebted, polluted and overbuilt than ever. Fixing those problems—and preventing them from getting even worse—means letting the Chinese economy slow and unemployment rise, perhaps dramatically. Are China’s leaders willing to accept that tradeoff to clean up the economy?

It sure sounds that way when president Xi Jinping encourages his people to “adapt to the new normal” of slower growth. But while this might seem like a pledge to stop stimulating the economy, the government has continued to goose growth, launching a slew of piecemeal measures that signal a reluctance to let growth fall below 7% in 2014.

Even without a big coordinated stimulus package, these are “starting to amount to something quite significant,” said Zhang Zhiwei, an economist at Nomura, in a recent note.

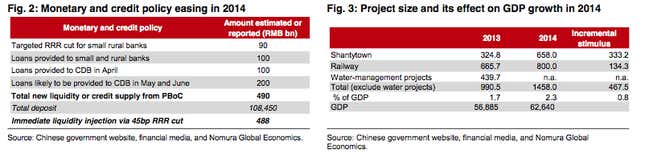

First off is the fact that premier Li Keqiang just told local officials to step up spending, apparently reversing his calls for them to eliminate wasteful factories. On top of that, Nomura points out that the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), China’s central bank, is set to inject about 400 billion yuan ($64 billion) into the economy by buying bonds to fund recently announced infrastructure projects, including building more railways and the renovation of “shantytowns,” as China’s urban slums are often called. Much of that will eventually go to the state-run China Development Bank, the “policy bank” that finances government infrastructure projects.

Since this new money flows from the central bank, it’s not part of China’s fiscal budget. The extra spending on shantytown renovation and railway build-out will boost GDP growth by 0.8 percentage points. That’s a big difference for a country that’s already struggling to meet it’s 7.5% GDP growth target for 2014.

What’s even more remarkable, though, is that the PBoC is essentially doing what the US’s Federal Reserve did with quantitative easing: printing money to buy government-agency bonds. Stephen Green of Standard Chartered calls this “more radical” than a cut (registration required) in the reserve requirement ratio (RRR)—the percentage of funds banks have to provision against loan losses—that many analysts have expected. Such a move effectively allows these banks to pump more credit into the system. (That said, while the PBoC hasn’t cut the RRR for major urban commercial banks, it did so for rural banks in mid-April.)

The question remains: If the government’s stimulating, why is it saying it’s not?

China’s leaders are worried about blowing the property bubble up even more than it already is, which risks heaping even more dangerous debt onto the financial system, says Nomura. Conventional credit loosening—e.g. interest rate cuts—risks doing that since it would broadcast to banks and borrowers that it’s okay to start lending like crazy again.

By quietly stimulating the economy in a way that it can control, the government may be able to offset the drop in growth that falling property investment will cause.