The EU and the US announced new sanctions against Russia today, with Europe banning a laundry list of activities and exports—no more pulsed electron accelerators or live Marburg viruses allowed—which the US matched by expanding its sanctions across several sectors of industry.

Short of Russian president Vladimir Putin halting his support for Ukrainian separatists, how can we tell if these measures are actually working? The US Treasury secretary, Jack Lew, offered a simple formula in a statement today: “We have seen sanctions bring the Russian economy to a standstill through a large and broad-based deterioration of Russian financial assets; capital flight that already exceeds all of last year; and a significant increase in Russian borrowing costs.”

In other words, they’re working already, and we should see the effects intensify. Let’s go to the charts.

Deterioration of financial assets?

What this basically means is, “Russians’ investments are worth less,” and a useful proxy is an index of Russia’s top stocks. It has suffered this year, both after the initial round of sanctions following Russia’s Crimean annexation (March) and once again as fighting increased in Ukraine and the MH17 disaster escalated the conflict (July). But it also appears that, at least in the short term, Russian equity markets are reacting more to the perception of escalating conflicts than the direct effects of sanctions. That, however, doesn’t mean Russian companies won’t begin to feel their bite, especially if financing costs rise.

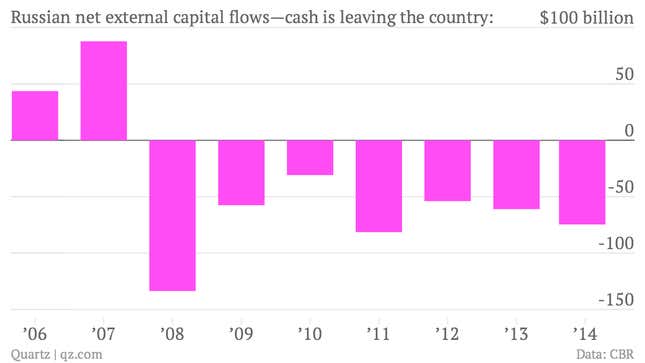

Capital flight?

Russia’s had a real problem with capital flight in recent years, as its wealthiest citizens and corporations have moved assets to tax havens and wealthy economies to avoid instability and political interference in Russia. (The erstwhile shareholders of Yukos, the oil company that the Kremlin seized and broke up in the mid-2000s, just won a $50 billion compensation claim in the Hague.) That left Putin plaintively asking oligarchs to bring back their cash, please. No dice: Capital flight has increased this year, already exceeding each of the last two years in preliminary data for the first two quarters of 2014. Is that the fault of the sanctions? In part—few investors want their money to be trapped if a new iron economic curtain is raised.

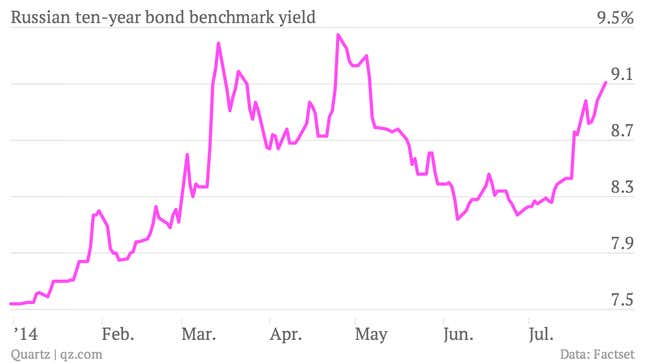

Increase in Russian borrowing costs?

You got it. Since the beginning of the year, the benchmark yield for a Russian 10-year bond has risen 157 basis points to 9.11%. Once again, you see it rise as the Ukrainian crisis escalates and recede as it calms. This is a big increase in the basic cost of doing business for the Russian government. Right now, other states are experiencing record-low borrowing costs—even debt-troubled countries like Spain and Italy have 10-year bond yields around 2.54%.