These men may revolutionize how you shop. There’s a reason they’re all Chinese

Imagine Donald Trump, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, and Google’s Larry Page unveiling a new, $814 million e-commerce platform to rival Jeff Bezos’ Amazon. Then imagine it involves customers buying goods on their smartphones but collecting them in person, that same day, from Walmart.

Imagine Donald Trump, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, and Google’s Larry Page unveiling a new, $814 million e-commerce platform to rival Jeff Bezos’ Amazon. Then imagine it involves customers buying goods on their smartphones but collecting them in person, that same day, from Walmart.

That’s pretty much what happened in Shenzhen on Aug. 29, except that the moguls involved were Chinese: Wang Jianlin, chairman of the real estate development giant Dalian Wanda Group; Pony Ma, head of social network giant Tencent; and Robin Li, chief of search engine Baidu. Their new, as-yet-unnamed joint venture focuses on ”online-to-offline”—a.k.a. O2O—retail.

In the age of Amazon.com, the idea of buying things online and picking them up at stores may not seem very exciting. But clearing the way for this type of channel-hopping has allowed a handful of big US retail chains to battle Amazon on its own turf. By letting people pick up goods in a matter of hours after buying them, O2O combines the benefits of online browsing with something closer to instant gratification than the two-day wait for Amazon’s Prime delivery service.

Synching up mobile apps with offline shops could, in theory, bring all your nearby merchants and restaurants into an interactive, “omnichannel” marketplace, connecting people in multiple ways to the goods and services around them.

Wanda’s Wang calls O2O ”the biggest cake in e-commerce.” And because of the different ways the retail market has developed in the West and in China, there’s good reason to think that it won’t be a Western e-commerce giant like Amazon, nor Western superstores chains like Walmart that get the biggest piece of this cake, but their Chinese e-commerce rivals.

Why China is different

In the US it’s been brick-and-mortar chains that have led the way in O2O. Retailers including Macy’s, Best Buy, and Walmart now let customers buy online and pick up their purchases later that day in the store or at a drive-through windows. This is proving a good way to win back sales from Amazon, and also limits the impact of “showrooming” (browsing in a store and then looking for the same goods at lower prices online).

These retailers also are innovating aggressively. Many now accept in-store mobile payment. In July, Target launched In a Snap, a mobile app that lets users learn about and bookmark products they photograph on their smartphones. Walmart, which rang up $9 billion in online sales in 2013, has lately been on a tech startup shopping spree, and most recently acquired Stylr, a location-based mobile app that helps shoppers find clothing items they have their eye on in nearby stores. Earlier acquisitions by Walmart Labs include Adchemy, which specializes in product search, and Yumprint, a recipe-discovery tech company. Meanwhile, home-improvement chain Lowe’s recently rolled out Holoroom, which lets customers use their iPads to remodel a room in 3-D:

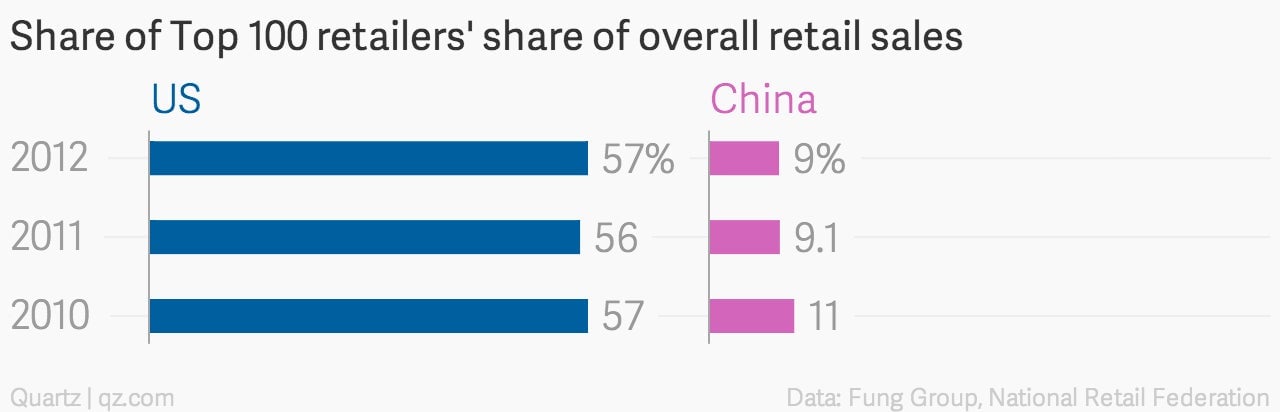

In China, by contrast, the O2O leaders are the biggest tech firms—Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu. One likely reason is that China doesn’t really have that many big brick-and-mortar chains, especially at the national level. The market is much more fragmented:

And that’s thanks, in no small part, to the Chinese government. China’s logistics system is governed by nine separate ministries and commissions, which prevents the central government from regulating cross-provincial transport across China’s 31 provinces. Instead, local governments manage their transportation systems as provincial fiefdoms, often using local license rules and tolls to raise revenue. Thanks to high transaction costs (pdf, p.28), no trucking firm has yet established a nationwide network. The state mail service, China Post, having long enjoyed both a monopoly on domestic delivery service and much more profitable side businesses (for instance, community banking (pdf, p.11) and hotels) has had few incentives to guarantee speedy or even reliable delivery outside China’s biggest cities. Sending a package from Shanghai to Beijing can cost more (paywall) than shipping it to America.

Before the internet era, this rats nest of a logistics system wiped out any returns to scale that would have come from managing store inventory for a national chain, or even a large regional one. As a result, no domestic national-scale retailers ever emerged (the notable exceptions being big-box electronics companies Gome and Suning, as well as supermarket chains). Even China’s biggest department stores only operate in a few regions (pdf, p.13).

This didn’t just keep the retail market fragmented; it also kept it unusually small. As of 2008, China had only 549,000 retail enterprises, compared with the US’s 1.1 million. That averages out to about 416 stores per one million people in China; every million Americans that year had 3,620 retail outfits to buy from. For any customers outside the very biggest cities, product selection was dismal.

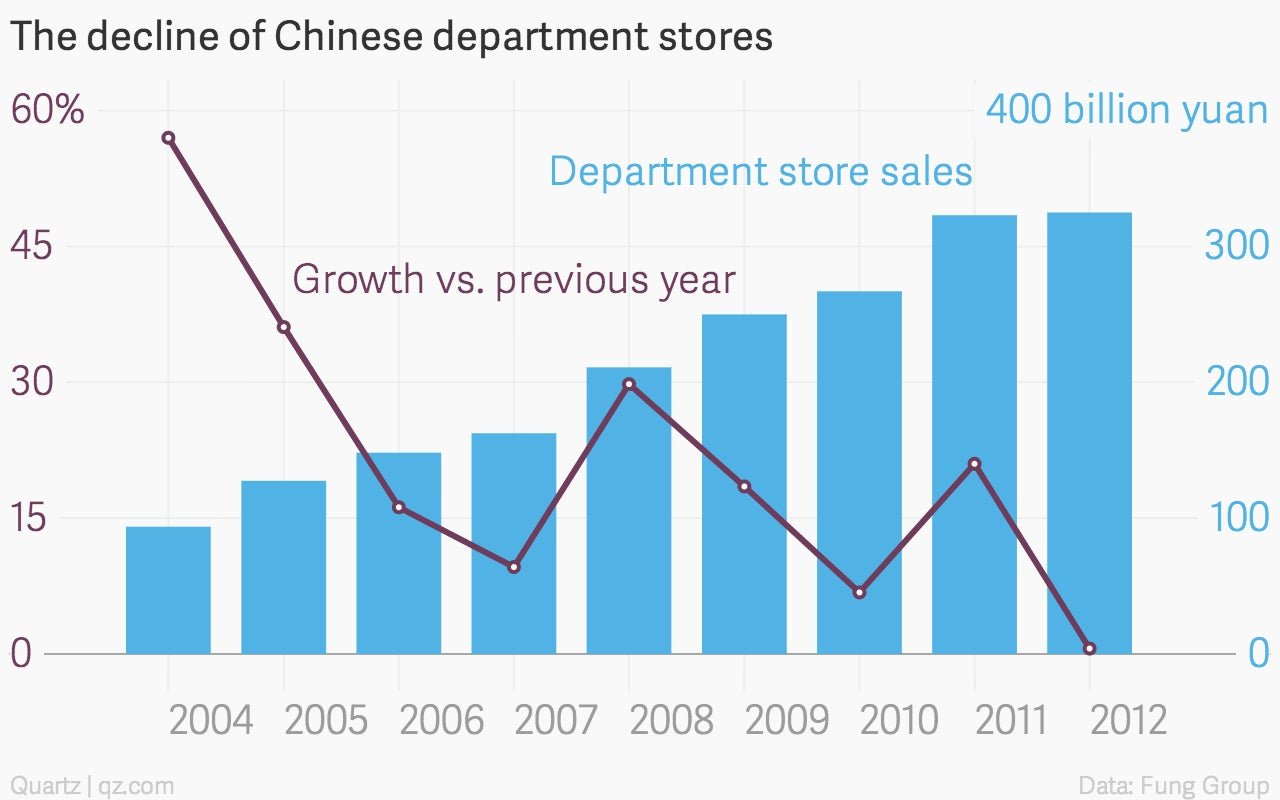

Online shopping revolutionized that. In apparel, for instance, the problem that Western e-tailers have—that customers are reluctant to buy clothes online that might not fit—simply doesn’t exist in China. People simply order clothes and try them on while the courier waits, returning anything that doesn’t work—a phenomenon called “mobile fitting room” (pdf, p.5). The result is that in those Chinese department stores that do exist, growth has come to a standstill:

Of course, the same lack of reliable shipping services that plagued China’s brick-and-mortar stores is a problem for e-commerce firms like Alibaba too. Alibaba got around this by encouraging customers to accept packages at their workplaces and partnering with small, private courier firms, which it endorsed to sellers on its site. Quality control remained a problem, however, and, since those couriers’ coverage was patchy in many regions, many packages were still shipped via China Post.

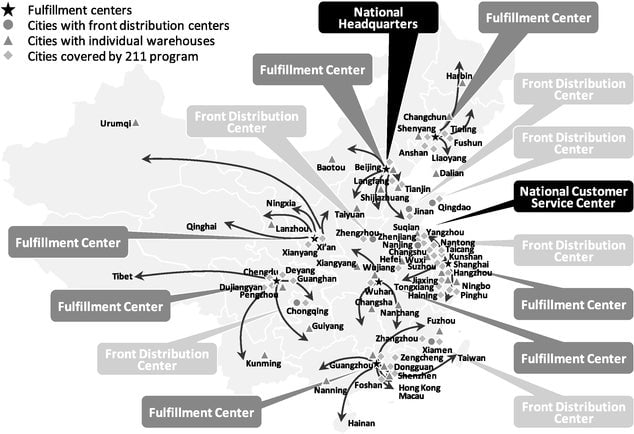

Nonetheless, Alibaba’s success was self-perpetuating. Once e-commerce started dominating the retail market, it attracted more buyers, which attracted more sellers, and so on. For retail chains, the cheapest way to reach the biggest customer base was to sell through Alibaba’s TMall or JD.com (of which Tencent owns 15%)—both of which now offer in-house delivery services for items sold on their platforms. A map of JD.com’s distribution network gives you a sense of its reach.

O2O: East vs. West

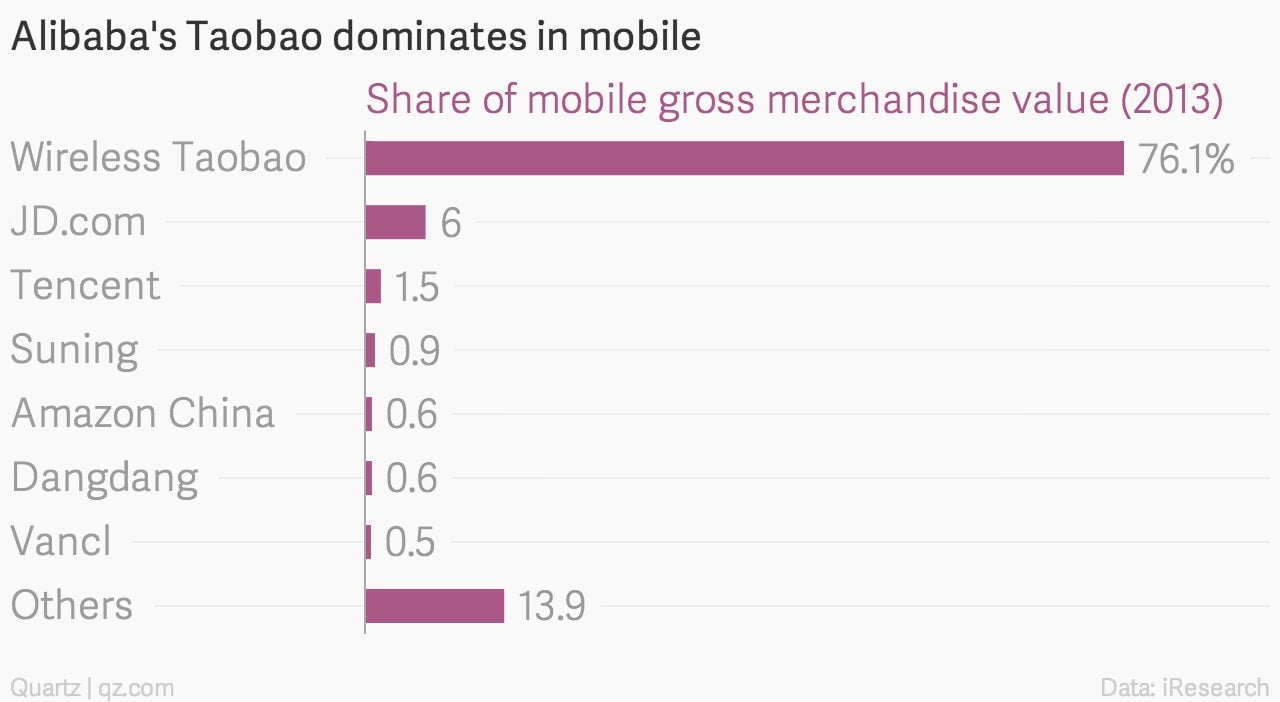

As a result, it’s been e-commerce firms that have led the way in retail innovation in China. Here’s a look at some of Alibaba’s and Tencent’s recent investments:

The new joint venture between Tencent, Baidu, and Wanda kicks all this O2O shift into a higher gear. Wanda is China’s biggest property owner; it claims huge swaths of the country’s choicest urban real estate, including a leading department store chain, hundreds of movie theaters, and acre upon acre of commercial plazas. Its tie-up with Baidu and Tencent, two digital powerhouses, pits them directly against Alibaba Group, which has been furiously developing its own O2O capabilities and will have even more capital to do so after its IPO on the New York Stock Exchange later this fall.

There are a few immediate opportunities for these firms to go after. For instance, they could expand into the realm of goods that don’t survive delivery very well—perhaps because they’re too big, too delicate, too expensive, perishable, or require in-store setup. To name one example, Alibaba’s Taobao Marketplace just teamed up with China’s biggest auto dealer to build a used-car sales platform that will offer a reliable history of the car you’re buying, as well as test-drives, financing and after-sales service.

A bigger money-spinner, though, is mobile payments and services. Both Alipay, the Alibaba-affiliated payment platform, and Tenpay—which is offered through Weixin (a.k.a. WeChat), Tencent’s blockbuster social media app—now have the bank-account information of millions of customers, many of whom are using their apps to pay for things like movie tickets and taxi rides. Enabling the apps at brick-and-mortar retailers would potentially let Alibaba and Tencent—or its new joint venture—tap into even bigger new streams of commission revenue.

The power of local

In the long run, though, the opportunity to link mobile users to local services might be even more exciting. Baidu’s Robin Li explained it this way: “One day you are walking in [one of Wanda’s shopping plazas] and spot a girl with a nice dress. You just take a picture of her, and then you will know immediately which store in the Wanda plaza is selling the dress.”

Tencent, for example, is rolling out features on Weixin that not only let users pay for restaurant meals, hotels, or pharmacy prescriptions with their phones, but also enhance those services. For instance, users can page waiters or open their hotel rooms through the app.

Meanwhile, Baidu just invested in a Finnish startup whose technology could let businesses guide customers through their store, alerting them to discounts along the way. Earlier this year it launched Baidu Connect, a smartphone platform on which consumers can browse services in a given area, book appointments, and pre-pay. This comes partly in response to consumer demand; Baidu says that between July 2013 and July 2014, user queries for services—as opposed to information—rose 133%. And the company’s answer to Google Glass—called BaiduEye—uses image recognition to search a huge database of clothing and accessories sold both online and offline.

Gu Jiawei, Baidu’s designer, told Bloomberg, “For us, the shopping mall is the most attractive scenario. Consumers can see what a product is and get online comments.”

But the “cake” Wanda’s Wang mentioned is much more than just the China market. When a company like, say, Walmart is leading the O2O charge, the goal is ultimately to sell as much Walmart stuff as possible, which puts a ceiling on the innovation it will pursue. For the Tencent-Baidu-Wanda venture or for Alibaba, there’s no limitation: If it can be sold offline, it can be sold online and via smartphone apps.

The emergence of this new joint venture, right as Alibaba prepares its IPO, means that the race is officially on. And that competition makes it more likely that if a company figures out how to bring all these O2O functions together in a way that revolutionizes shopping, chances are good that it’ll be from China.