Hong Kong’s pro-democracy civil disobedience movement appears to be losing some steam, as the numbers of protesters dwindle and the groups behind the demonstrations seek to negotiate a exit. But even if the protesters return to school and work, they can always return—and that means China’s leaders can’t rest easy.

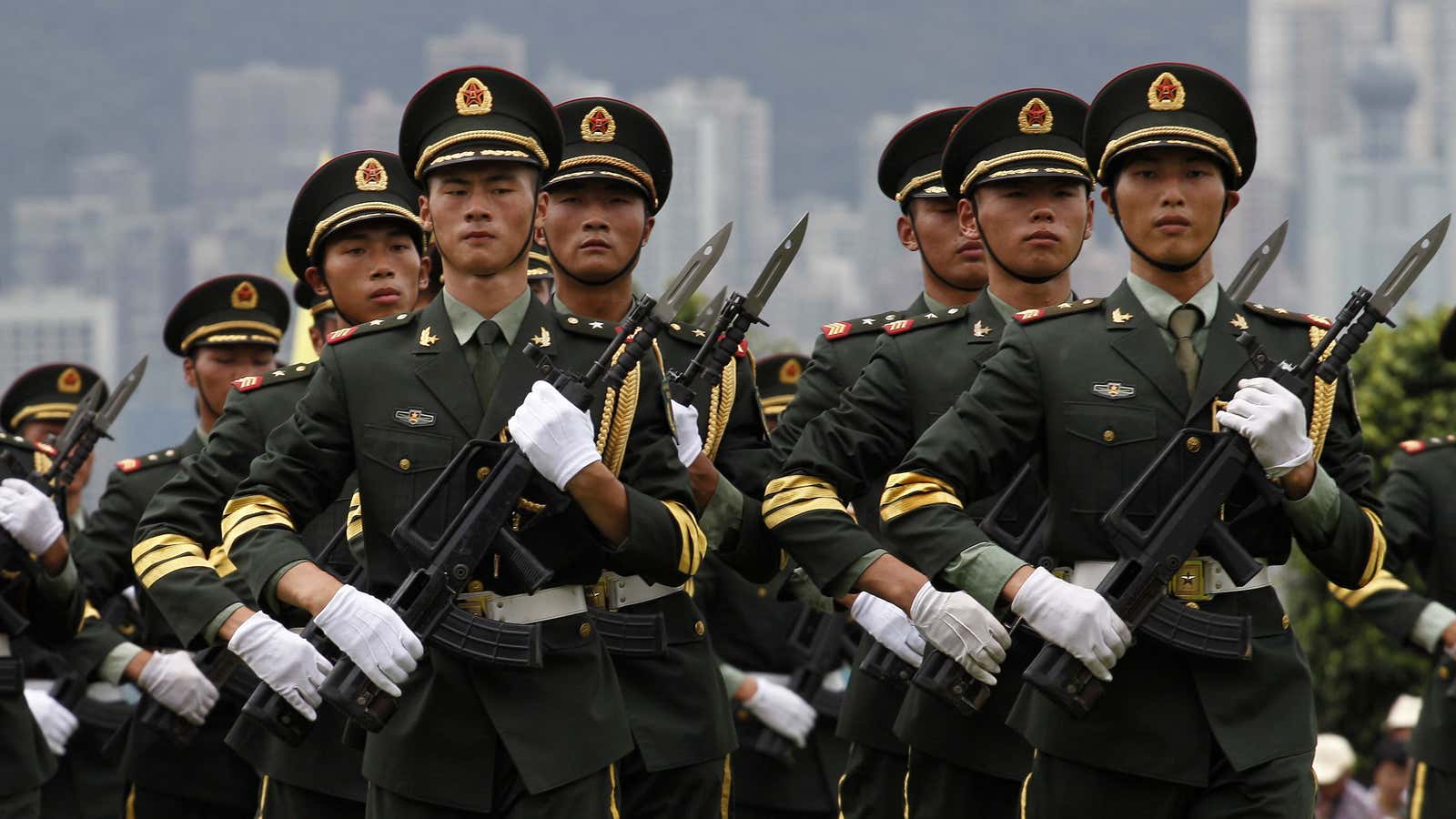

Though the Chinese Communist Party has control of the world’s second-largest economy and its largest standing army, those vast forces aren’t nearly as useful as they might seem for defeating a protracted protest movement.

Physical intimidation is counterproductive

Attempts to strong-arm the mostly peaceful protesters has only helped their cause so far. When police blasted protesters with tear gas and pepper spray on the evening of Sep. 28, popular outrage sent thousands of residents to the streets in support of the movement, notes Steve Tsang, a professor of contemporary Chinese studies at University of Nottingham. And when reputed organized crime figures and other pro-Beijingers roughed up the protesters in Mongkok last weekend, it only drew more demonstrators to their defense.

Hong Kong’s economy is hard to disrupt

Economic reprisals—like Beijing’s freezing of tourist visas for mainlanders, who tend to spend heavily in Hong Kong shops—might have some effect. Along with generalized business disruptions caused by the demonstrations, lower tourist spending could help fuel local businesses’ resentment against the demonstrators.

But the threat is not really that menacing. Since retail and tourism make up a teeny fraction of the economy, even a year-long occupation of downtown Hong Kong would drag down the territory’s GDP by just 1%, argues Richard Harris in the South China Morning Post (paywall). As for the blow the protests might deal to the financial sector, only about 15% of the Hang Seng stock index comprises companies sensitive to events in Hong Kong, says Harris.

The less the protesters disrupt the economy, the longer they can hold out—and the more media attention they win for their argument that true “universal suffrage” for chief executive elections isn’t possible when Beijing insists on screening the candidates. All the while, the global reputation of China’s leaders will suffer, as will its credibility with Taiwan—a democratic country claimed by China with which PRC leaders are trying to forge a closer relationship—and in restive regions, like Xinjiang, Tibet, and, increasingly, Macau.

The Tiananmen option would cause chaos

Even if unrest intensifies, deploying mainland troops would require the suspension of the very rule of law that makes Hong Kong a financial center of China.

Hong Kong law explicitly says that China’s military shall not interfere in Hong Kong, says Fu Hualing, law professor at the University of Hong Kong, in a recent blog post. There are two exceptions: Hong Kong’s chief executive can request military assistance from PLA troops garrisoned in Hong Kong for defense purposes; and China’s central government can also send in troops from the mainland—but only if there is turmoil that endangers either national unity or security and is beyond the control of the Hong Kong government.

Either way, deploying troops in Hong Kong would be “a disaster that neither Beijing nor Hong Kong wish to see,” Fu writes.

The economic consequences wouldn’t just devastate Hong Kong’s economy; they could also send investors in mainland China running for the exits, says Andrew Scobell, senior political scientist at Rand Corporation.

“Hong Kong can continue to function [with the current level of protests]. The economy can continue to chug along,” he says. “But if things escalate, if things get out of control, if Hong Kong or the Beijing authorities feel the need to crack down… then that’s when you see the specter of an outflow of capital.”

Right now, the Chinese financial system is increasingly hooked on money flowing into Hong Kong from abroad. If that flow stops, it could easily cause the sort of panic that happened in June 2013, when banks stopped lending to each other and credit froze up. For a country where non-financial corporate debt now stands at 150% of GDP, that would be disastrous.

Beijing is a lot less intractable than it lets on

The Chinese government has backed down before in its efforts to rein in Hong Kong freedoms, notes Scott Harold, also a Rand political scientist.

“It’s worth remembering that in 2003, the Hong Kong government tried to push through a very restrictive public security law… and when the masses came to the street that law was pulled back and shelved indefinitely,” says Harold.

Something similar happened in 2012: when the government tried to institute mandatory “patriotic” education, it inspired a popular backlash that created Scholarism, the student movement leading the protests today. The government also ended up allowing the village of Wukan, in Guangdong Province, to run free and fair elections for party representatives after the villagers staged an uprising in late 2011.

But that’s not the image China’s leaders like to project, says Harold.

“The notion that China cannot compromise is in fact a part of China’s bargaining leverage,” he says. “They seek to portray themselves as incapable of compromising to convince others that they will have to compromise.”