HONG KONG—In the 2012 sci-fi novel, Hong Kong Shutdown, the city is in chaos. Transportation is wrecked, the government is paralyzed, the police have resorted to violence, and mainland Chinese officials have swooped in to address the problem—a virus that hit the city of seven million—by cutting off Hong Kong from the rest of the world.

“It reminds me of Hong Kong today,” Shephard Ng, 22, tells Quartz, as he plucks the novel from a stack of used books that has just been wheeled into the main protest site of Hong Kong’s “umbrella movement,” which has floored the city over the past week. In the face of a government-issued ultimatum to leave protest sites by Monday morning, when police are rumored to arrive, some protesters are instead setting up a small community library there, a symbol of their determination to achieve free elections.

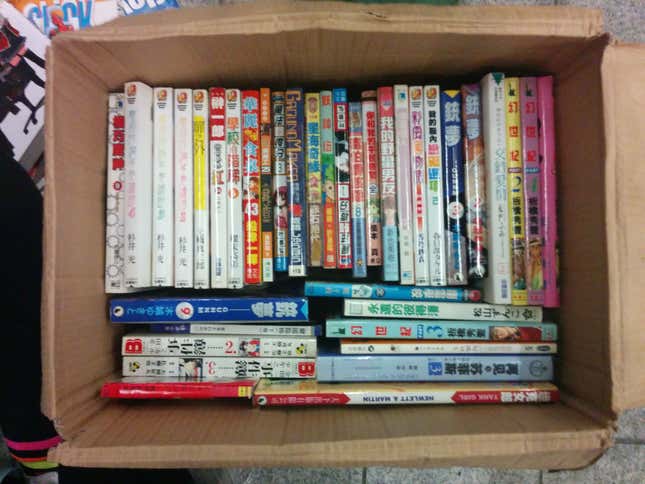

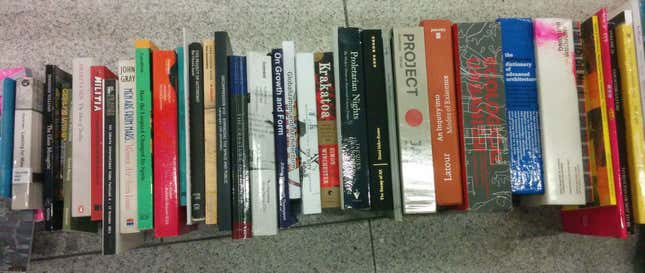

On a plaza in the Admiralty area of downtown, where thousands of demonstrators are sleeping on makeshift beds outside government offices and along a main thruway, the lending library boasts an English section, a Manga collection, and several shelves of books in Chinese. Titles range from How to Survive a Robot Uprising, and Dante Alighieri’s Inferno to On Democracy by Robert Dahl. The library is situated near the office of the city’s embattled chief executive, CY Leung, and a ”mobile democracy classroom” where demonstrators hash out the links between free elections and environmentalism.

“We hope we can fuel discussion. We want to let people know more about democracy,” says Soman Wong, a social worker in Hong Kong, who at one o’clock in the morning is stacking books on a small wooden shelf, anticipating government workers returning to their offices nearby. Asked how long she thinks the protesters will stay, she says, “Until the government changes” and then adds, “As long as we can.”

One student group involved, the Hong Kong Federation of Students, held preparatory talks with government representatives after protesters pulled back from some protest sites earlier in the evening, according to the group’s Facebook page. The government has now asked that protesters clear the main road in Admiralty as well as areas near government offices to let workers back in come morning.

Hong Kong’s pro-democracy demonstrators, many of them students who have now boycotted two weeks of classes, are at a turning point. The movement’s initial push for universal suffrage could be derailed by strategic disagreements among protesters, such as which sites to occupy and how to address pushback from authorities. Some student leaders began talks with government representatives late Sunday evening, while other protesters vowed to hold out for meaningful government concessions. “They can’t stop us now. Not even the leaders [of the protests],” says Chung, Pui-Man, 20, a student at Chinese University of Hong Kong, standing among the remaining hundreds of protesters along Harcourt Road, the main street in Admiralty.

The movement has also been threatened by attacks on protesters and scuffles with local residents angered by blocked traffic in major intersections and commercial districts. On Sunday evening, Admiralty was less crowded than it has been all week; secondary school teachers advised their students to stay at home out of fear of violence and at least one university head pleaded with protesters to evacuate.

Wong hopes the lending library—which also includes titles like Guard Hong Kong, a collection of letters between residents of Hong Kong and Tokyo about their cities and Proletarian Nights, on the workers movement in mid-19th century Paris—will reinvigorate the movement. One protester helping put together the library points to a copy of Noam Chomsky’s Media Control on the connection between government and media, and says, “This is just like Hong Kong’s TVB,” referring to a local pro-Beijing television station.

Other protesters like Chung, who plans to stay in Admiralty until the morning, are less bleary-eyed. ”Deep down, you wonder, will it work? Probably nothing is going to change. We just fight for something.”