Among the many notable details about Verizon’s $4.4-billion bid to acquire AOL, one doesn’t have anything to do with mobile video, online ads, or other technological concerns. Take a look at the financial advisors on both sides of the deal: LionTree Advisors and Guggenheim Partners for Verizon, and Allen & Company for AOL.

It’s a boutique advisor shutout—not a single “bulge bracket” bank got a piece of the action. When AOL and Time Warner merged in 2000, the list of advisers included heavy hitters like Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch.

This is just the latest sign of boutique banks muscling in on the big boys’ turf. Zaoui & Co, founded in 2013 by two brothers who made their names doing deals at Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, have advised on several high-profile deals this year, including Nokia’s bid for Alcatel-Lucent. Robey Warshaw, founded last year with only nine staff members by former Morgan Stanley and UBS bankers, played a big role in Shell’s bid for BG last month. Former Morgan Stanley stalwart Paul Taubman set out on his own in 2012, and within a year his PJT Capital had advised on deals worth $175 billion as a one-man band.

The list goes on. Boutique advisory firms took home around 30% of global M&A fees last year, according to Thomson Reuters Deals Intelligence. (A boutique is defined as a firm that derives at least 70% of its income from dealmaking fees.) Boutiques’ share of fees has nearly tripled since 2000.

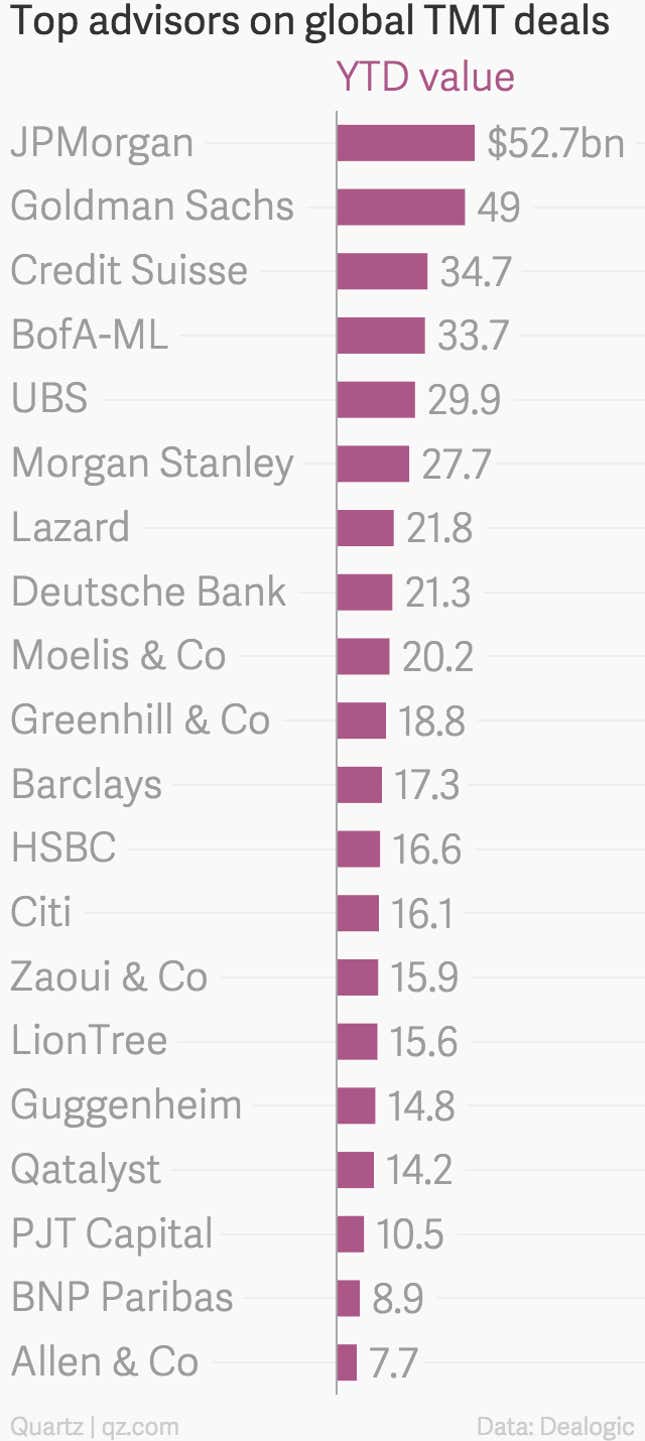

The boutiques, mostly run by rainmakers who cut their teeth at bulge bracket banks, will never be able to scale like their biggest rivals, but they are finding plenty of profitable niches to mine—including the technology, media, and telecom industries (see chart at right). LionTree Advisors, which after its founding in 2012 has rapidly established itself as a media dealmaker, advising on Liberty Global’s takeover of Virgin Media and others before Verizon-AOL came along. The impetus for the Verizon-AOL deal came from a meeting between the CEOs last year at Allen & Company’s annual conference for media moguls.

Small is beautiful

For companies, the appeal of employing boutiques comes—somewhat ironically—from tapping the networks that their advisors typically established while working for bulge bracket banks. But free from the pressure, friction, and distraction that comes with working at a big bank, boutique advisors claim that they are free to focus more senior-level, personal attention on clients.

A drawback of their size is that they cannot muster in-house resources to provide significant financing to get transactions done, limiting them mainly to advising on all-share or all-cash deals (like Verizon-AOL). But the benefit of a smaller number of advisors and modest infrastructure—many boutique’s staff “could comfortably fit in a minibus,” as Bloomberg memorably put it—is larger payouts for each partner when a deal gets done, which focuses the mind. “If we do one deal a year, that’s fantastic,” a boutique partner told Bloomberg.

And those deals are adding up, which is bad news for the bulge bracket. Advisory fees represent a relatively stable, profitable line of business without the volatility or capital intensity of trading operations. As M&A animal spirits are stoked, big banks will rue the fees they lose to the boutiques. Whereas once they crowded into just about every high-profile deal, they now must share the spoils with the small fry—or sometimes come away with nothing at all.