Here’s what you need to know about China’s currency devaluation

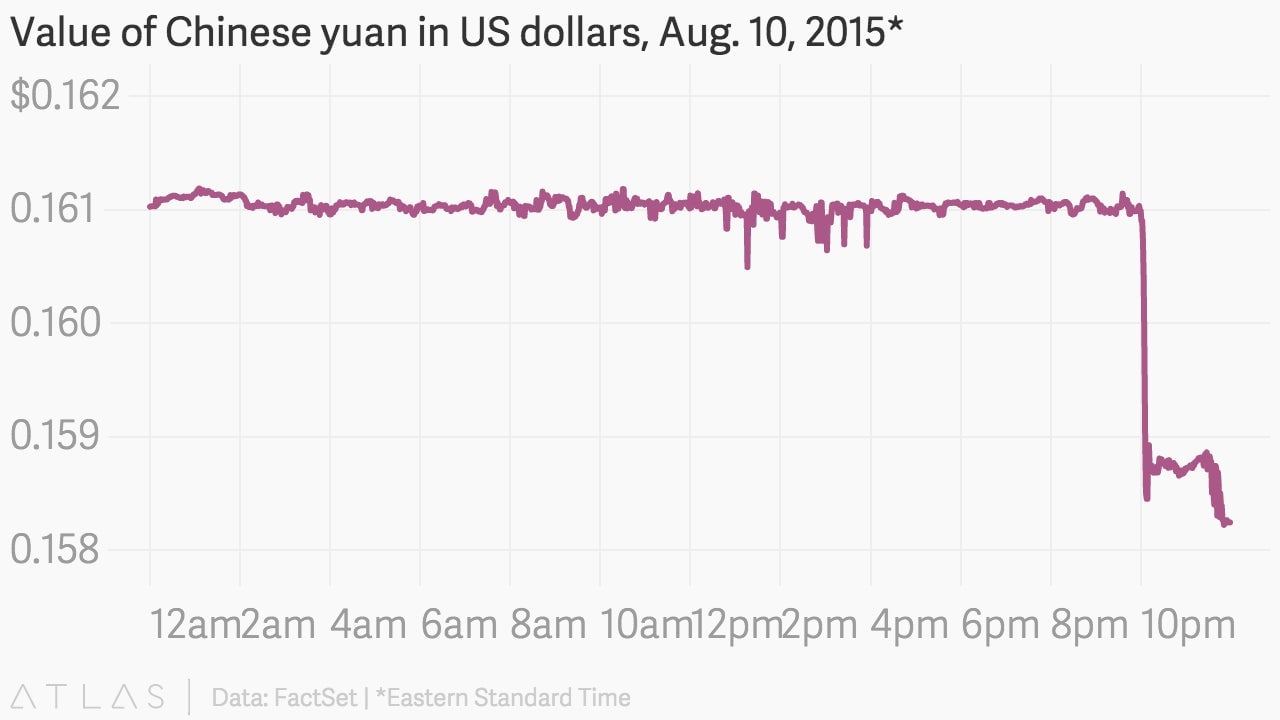

China surprised global markets Monday (August 10) with its decision to devalue its currency, the renminbi, by nearly 2%. That might not seem like much of a move, but China is the world’s second largest economy and controls its currency pretty tightly. Any policy move like this is big news in the world economy. Here’s what you should know:

China surprised global markets Monday (August 10) with its decision to devalue its currency, the renminbi, by nearly 2%. That might not seem like much of a move, but China is the world’s second largest economy and controls its currency pretty tightly. Any policy move like this is big news in the world economy. Here’s what you should know:

Why did China do it?

In a statement, People’s Bank of China officials offered up a few hints, chalking up the move to financial reform: “For the purpose of enhancing the market-orientation and benchmark status of central parity, the PBC has decided to improve quotation of the central parity of RMB against US dollar.”

In a Q&A posted to the PBOC website, officials were a bit clearer, adding that the policy change is meant to give more control over its currency to markets. So why would China want to do that? Because the International Monetary Fund is considering adding the renminbi to its basket of global reserve currencies, which is more a matter of status for China than practical benefit. For that to happen, the yuan needs to be considered fairly valued. Assuming that the Chinese government keeps its word to allow markets to play a bigger part in determining exchange rates, this is a positive move in that direction.

How did markets react?

They freaked out a bit. Commodities took a hit because China is one of the world’s largest consumers of raw materials, from iron ore to cotton to milk. Plus, European stock markets from Germany to Norway took a nosedive on the news. That’s because China has been a growing market for European exports, and the devaluation would make any imports more expensive to the Chinese.

Some worry that the move might be signaling other issues. Jorge Mariscal, emerging markets chief investment officer UBS Wealth Management, suggested that a relatively sudden Chinese devaluation might mean the country’s economy is slowing even more than the government has been letting on, which is spooking traders. “They’re asking themselves: What do the Chinese see that we don’t?” he told Quartz.

What does this mean for me?

It depends:

- If you’re running a Chinese business that imports goods, your costs just increased.

- If you sell a lot of goods in China, you could see a slip in demand because the Chinese have less purchasing power. That could be especially problematic for a luxury goods business.

- If you’re running a business outside China that sources goods in China, your costs just decreased.

- If you’re a Federal Reserve official waiting for inflation to return so you can raise interest rates, the prior development will make that job a little harder.

- If you’re a finance minister in a country whose exports compete with China’s, traders are going to put your currency under pressure because your economy might take a hit.