Volkswagen’s share price looks like it’s been driven off a cliff:

For good reason. After VW was caught trying to cheat US emissions tests, its brand has been sullied, its chief executive has resigned, and it faces possible criminal charges and up to $18 billion in fines. The company is in full-blown crisis management mode, and hired the same lawyers who defended BP after its Gulf of Mexico oil spill to help contain the fallout.

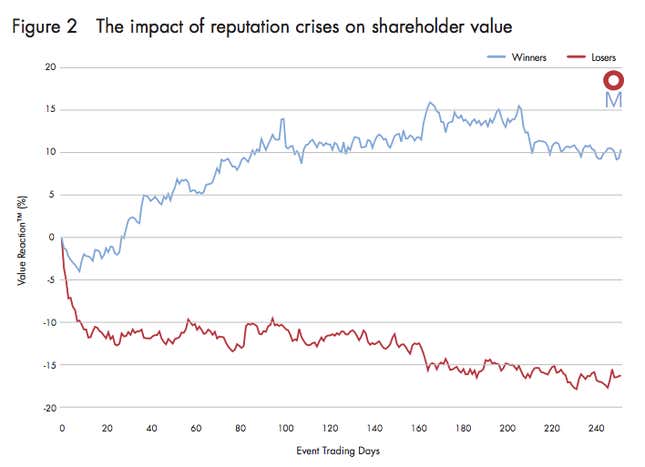

But all is not lost. Some companies don’t simply recover from a major crisis, but thrive. Research firm Oxford Metrica claims (pdf) that while crises like the one at VW are often extremely damaging initially, there is a significant minority of companies who emerge and grow more valuable in the long-term—more so than if they’d avoided disaster in the first place.

Drawing on a large database of historical “reputation events,” the research firm says that the average “losers” see their shares drop by 10% almost immediately and lose another 15% in value over the subsequent six months. By contrast, the “winners” surpass their pre-crisis valuation within a month, and gain another 15% within six months. Oxford Metrica strips out unrelated background market activity, isolating the share movements that it thinks are down to the effect of a crisis alone.

Deborah Pretty, principal at Oxford Metrica, tells Quartz that disasters can eventually add value to a company because they reveal new insights into how a company operates. Shareholders get a closer look at management and how they behave under pressure. If they like what they see, they boost the value of the company.

“The share price recovery is all about the future,” Pretty says. “The costs [of the crisis] will, at some point, all be historic, and the share price is about future performance, future cash flow. It’s a recovery story.”

Pretty points to Air France as an example of a “winner” due to its response following a Concorde crash in July 2000. Chief executive Jean-Cyril Spinetta attended memorial services and didn’t dispute compensation. “The loss of life clearly impressed itself upon him deeply and he responded accordingly,” says Pretty.

Spinetta’s behaviour was understandably better received than former BP boss Tony Hayward, who complained that he wanted his life back following the 2010 oil spill. While BP’s share price hasn’t recovered in the five years since, Air France generated value after the crash.

“I don’t think it’s inevitably bad for VW,” Pretty says. “I think it can be repaired.”

Maybe so, but the company will have to act fast, as Pretty says that the market tends to make a decision within the first two weeks of the crisis. Volkswagen also faces particularly strong obstacles because its crisis comes from deliberate actions, rather than an accident.

Leslie Gaines-Ross, chief reputation strategist at communications firm Weber Shandwick, is hopeful. “Volkswagen will recover and they’ll be better,” she tells Quartz. The author of CEO Capital: A Guide to Building CEO Reputation and Company Success says Volkswagen must now appoint a new boss and communicate clearly with the public and discouraged employees.

“In the end, it can be an opportunity because they get to fix systemic issues that have been boiling below the surface,” she says. “It will take a long time, but I think we’ll see that good will come of it.”