If you want to know how to make money on mobile apps in China, you should probably look at how Hollywood makes money on its films in that country. The parallels are uncanny: In movies, it’s action films that do best; in apps—or more specifically games—it’s the same. Simplicity, a conspicuous absence of plot, and lots of violence and/or explosions are, it seems, the DNA of popular entertainment.

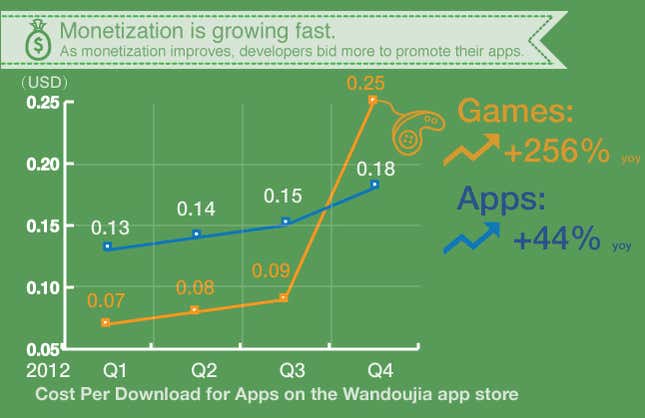

Check out this chart from Chinese app store Wandoujia.

As in the US, apps are dominated by social media and utilities, and companies from outside China represent just 1 in 10 of the most downloaded apps (i.e., Google Maps). But games are a completely different story, with 7 of 10 game apps coming from outside China, and primarily US development studios.

The Sinofication of blockbusters

Clearly, games travel in a way that other apps do not. But it’s not just that they have an inherently universal appeal. All of these games have been localized to the Chinese market, with translated text and menus, at the least. And those who know this market are urging developers to go even further, localizing themes, characters and even game-play to suit Chinese tastes.

The same thing is already evident in Hollywood blockbusters, which are adding Asian characters and changing plot points, like shifting the future world capital in the Sci-Fi movie Looper from Paris to Shanghai for its Chinese release. Foreign game studios that are ahead of these trends are reaping big rewards in China already. As early as 2011, Shainiel Deo, head of Australia-based Halfbrick Studios (makers of Fruit Ninja) said China was the company’s “number one market.”

Developers who watch the China market are projecting that 2013 will see 10x year-over-year growth in revenue from games, for a couple of linked reasons. One is that developers simply didn’t make that much money on games in China in 2012. But that’s a consequence of the hundreds of different Android app stores in China having difficult-to-use payment mechanisms that hardly resemble the one-click purchasing possible in Apple’s app store and Google’s Play store. (Google’s Android smartphone software—rather than Apple’s iOS—runs on over 90% of Chinese smartphones sold.)

In 2013, two things are happening: The first is that at least 76 million Chinese will be added to the ranks of those who have Android smartphones, swelling them from 224 million to 300 million. More importantly, those hundreds of fragmented app stores with their challenging payment mechanisms will consolidate to tens of app stores, and more or less all of them capable of one-click purchasing via what’s called carrier billing.

Carrier billing—buy something on your phone, and it simply appears on your mobile connectivity bill from your telecom service provider—is the same thing driving the revolution in mobile banking throughout Asia and emerging markets. As Apple discovered when it leveraged all the credit card numbers it had acquired through iTunes, when you give users the ability to spend money with just a button-tap, they will spend like crazy.

Here come the censors?

Even the future of apps in China is likely to resemble the film industry. For one thing, the Chinese government currently restricts the number of Hollywood blockbusters allowed into the country every year—the current cap is 34—and the content of movies is also vetted by censors. As apps become a bigger business—globally, the video game industry is already making more money than Hollywood—it seems unlikely that the authorities in China will continue to ignore them. Especially if the consolidation of app stores and carrier billing gives them a central locus of control.

The authorities are already paying attention to mobile devices on a macro level, as evidenced by the state media’s PR war on Apple and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology releasing a report stating that China is already too reliant on Android.

One thing that’s distinctly different between apps and movies is that in China, many games cannot become blockbusters unless their developers pay to get them a high position in an app store in the first place. This is called shuabang, and it makes it less likely that independent games, whose developers may not have the same marketing budget as big studios, will succeed.

According to Wandoujia, source of the earlier graphic in this piece, for games at least, shuabang is more important than ever—and much more important for games than for non-game apps.

So given all the similarities between the global game app industry and other forms of entertainment like movies, is the future of games government restrictions on foreign titles and the Sinofication of blockbusters? Given the undeniable size of the Chinese market—and the rate at which it’s growing—it’s certainly a possibility.