Dear Wang Yi: Here are some Chinese people who would like to “have a say” about human rights

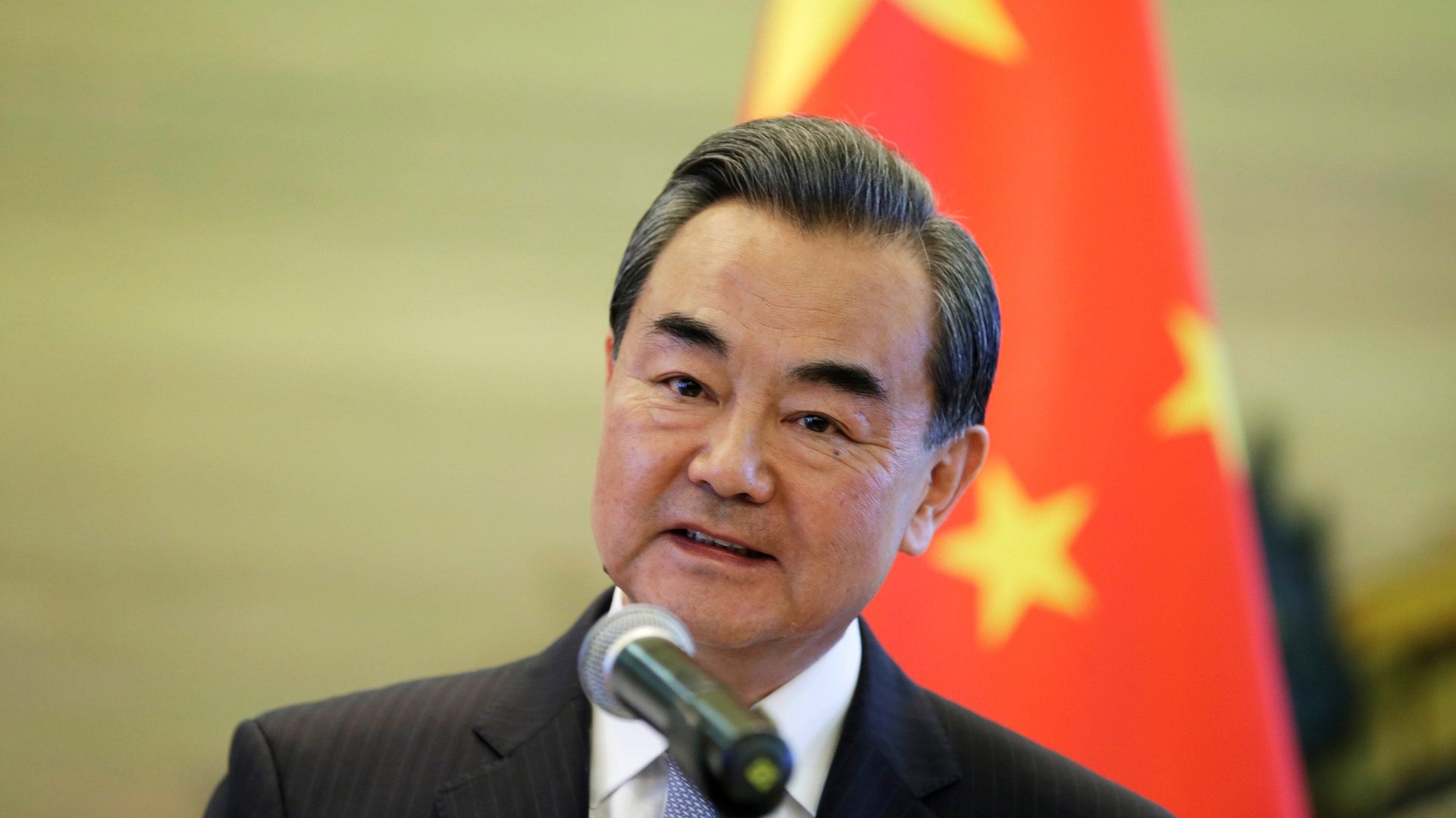

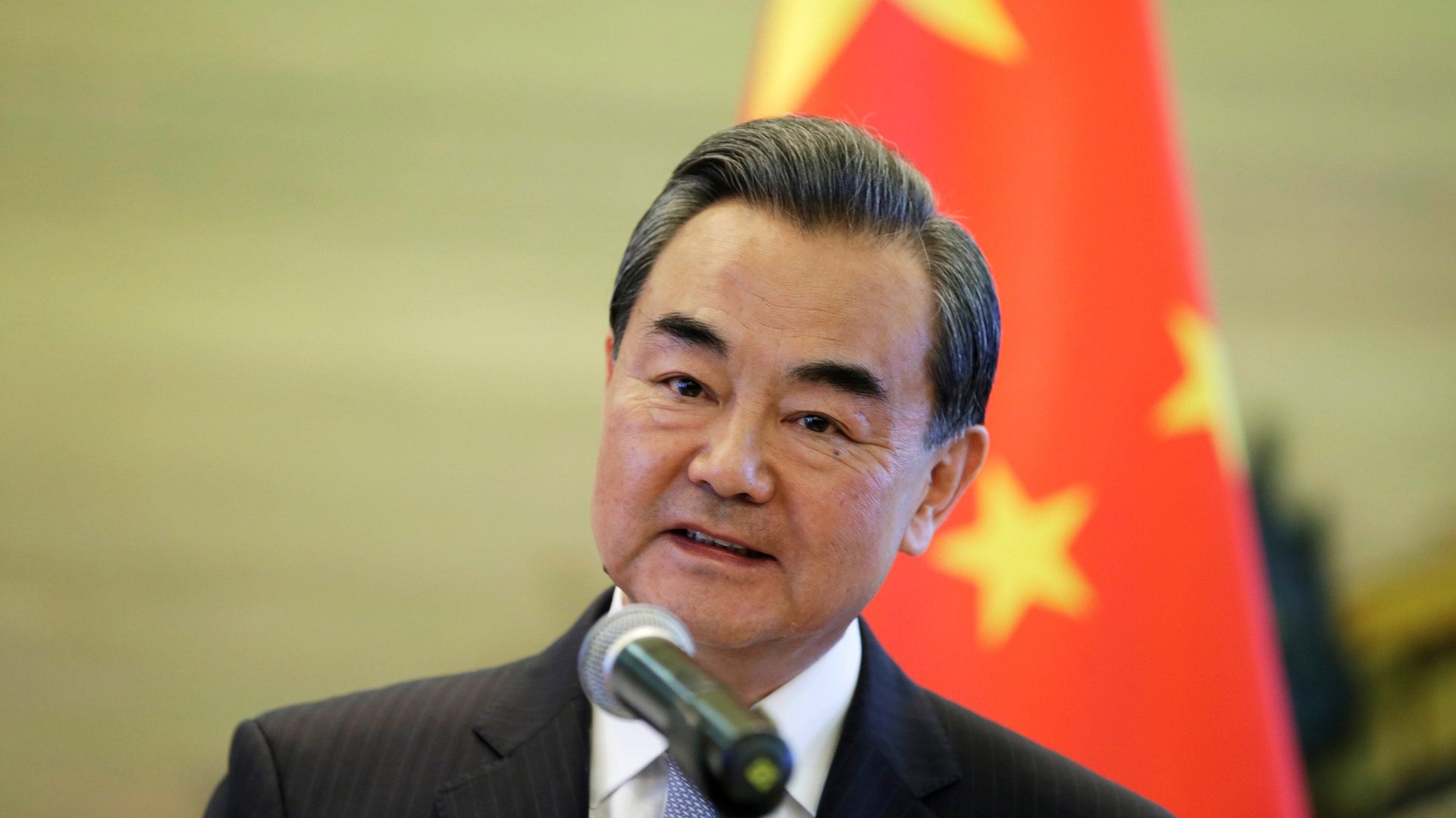

China’s foreign minister Wang Yi had a tense exchange with a Canadian journalist on Wednesday (June 1) during an official visit to Ottawa.

China’s foreign minister Wang Yi had a tense exchange with a Canadian journalist on Wednesday (June 1) during an official visit to Ottawa.

When a journalist from a pre-selected pool posed a question to Canada’s foreign minister Stephane Dion about China’s human rights record, and particularly the fate of Canadian Kevin Garratt, an aid worker China has charged with espionage, Wang exploded, the CBC reported:

“Your question is full of prejudice and against China and arrogance… I don’t know where that comes from. This is totally unacceptable.”

“Have you been to China?” he asked. The Chinese constitution has “written protection and promotion of human rights,” and China has pulled some 600 million people from poverty, he said, adding:

“Other people don’t know better than the Chinese people about the human rights condition in China and it is the Chinese people who are in the best situation, in the best position to have a say about China’s human rights situation.

Please don’t ask questions in such an irresponsible manner.”

A 2004 amendment to China’s constitution did, in fact, add the phrase “the State respects and preserves human rights” (the only mention of “human rights” in the constitution), and one of the original articles claims that citizens “enjoy freedom of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of procession and of demonstration.”

But the reality in China, and even for Chinese citizens outside the country, is much different. Speaking publicly about “human rights,” and particularly criticizing the ruling Communist Party’s approach to them, can get you a lengthy detention without trial, at the very least.

In the worst-case scenario, it can result in losing your job, being jailed for years, your family being constantly harassed by police, and even torture and physical abuse from local police. China’s highly censored journalists don’t ask officials questions about human rights during public press conference, pretty much ever. Which puts the onus on foreign journalists, governments, aid agencies, and others to keep asking.

Here’s how things turned out when some Chinese citizens tried to “have a say,” as Wang put it, about human rights in China:

- More than 150 human rights lawyers were detained last summer in a nationwide crackdown on the people who advise regular citizens of their constitutional rights. Many were tortured, forced to make “confessions,” and harassed, Amnesty International found.

- Parents of the students killed in the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 have been trying since then for “truth, accountability, and compensation” from the government, which has never acknowledged that the incident, in which hundreds and maybe thousands died, even occurred. Instead, members of a Tiananmen parents group have been harassed, detained, spied upon, threatened, and lied about, they said in a letter this week.

- Workers’ rights activists trying to help migrant factory workers collect the salaries and benefit they are owed have been locked up, sometimes without access to lawyers or family, and smeared in the press. When the family of one complained publicly and tried to use the legal system to defend him, they were harassed by police.

- Five women who planned a protest against sexual harassment were detained without being given lawyers or family visits until the situation attracted international attention.

- Two former Chinese nationals (one who was no longer a citizen at the time) were abducted from Thailand, reportedly by Chinese authorities, upset with what they had written about the state of the country and the party.

- A lawyer who defended more than 100 churches whose crosses were demolished by China’s government was detained for months in a so-called “black jail” in a secret location.

- A senior journalist in her seventies was detained for months for allegedly leaking “state secrets” to international media, before she was granted medical parole, after making a televised “confession” that she later recanted.

- Hundreds of Chinese investors, who may be out billions of dollars in one of China’s biggest financial scams, have been harassed, physically intimidated, and arrested for protesting to get their money back. Now they’re jumping the Great Firewall to seek international attention.

Despite the government-backed abuse and trampling of their constitutional rights, every day people in China try to “have a say” about human rights. It’s just something that Wang and other officials from Beijing don’t want to hear.