Music has been totally disrupted by Silicon Valley—yet it’s still run by the same two moguls

In music, as in life, making it big is often a matter of who you know. Talking of rising up his industry’s corporate ladder, Jay Z once rapped:

In music, as in life, making it big is often a matter of who you know. Talking of rising up his industry’s corporate ladder, Jay Z once rapped:

I’m getting courted by the bossesThe Edgars and Doug Morris-es-es

Jimmy I’s and Lyors-es

That last line referred to Lyor Cohen, who used to lead the massive Island Def Jam Music Group, and Jimmy Iovine, the former head of Interscope Records—two executives running powerful record labels that all but controlled the industry in the 1990s.

But music has since transformed. Almost entirely. In the early 2000s, Napster revolutionized things by making music free—unleashing a wave of digitalization and piracy—and the industry saw its traditional, label-controlled, CD-driven business model shatter. In 1999, the global music business was worth almost $30 billion; today, it’s valued at half that.

You’d think such massive changes would bring an upheaval in leadership. Yet who are the two names now helping to steer music into the future, at a time when newfangled streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music have finally become popular enough to cause an uptick in the industry’s decades-long downward spiral?

Lyor Cohen and Jimmy Iovine.

Cohen, who’s about to take over a crucial part of YouTube’s business, and Iovine, now Apple’s music guru, by all accounts should have crashed to the ground alongside the music industry’s antiquated business model—the way the executives who ran Nokia and Blackberry have been tossed aside by the smartphone revolution. But they did the opposite. So who are these two men, and how’d they pull off the near-impossible?

Apple’s true music genius

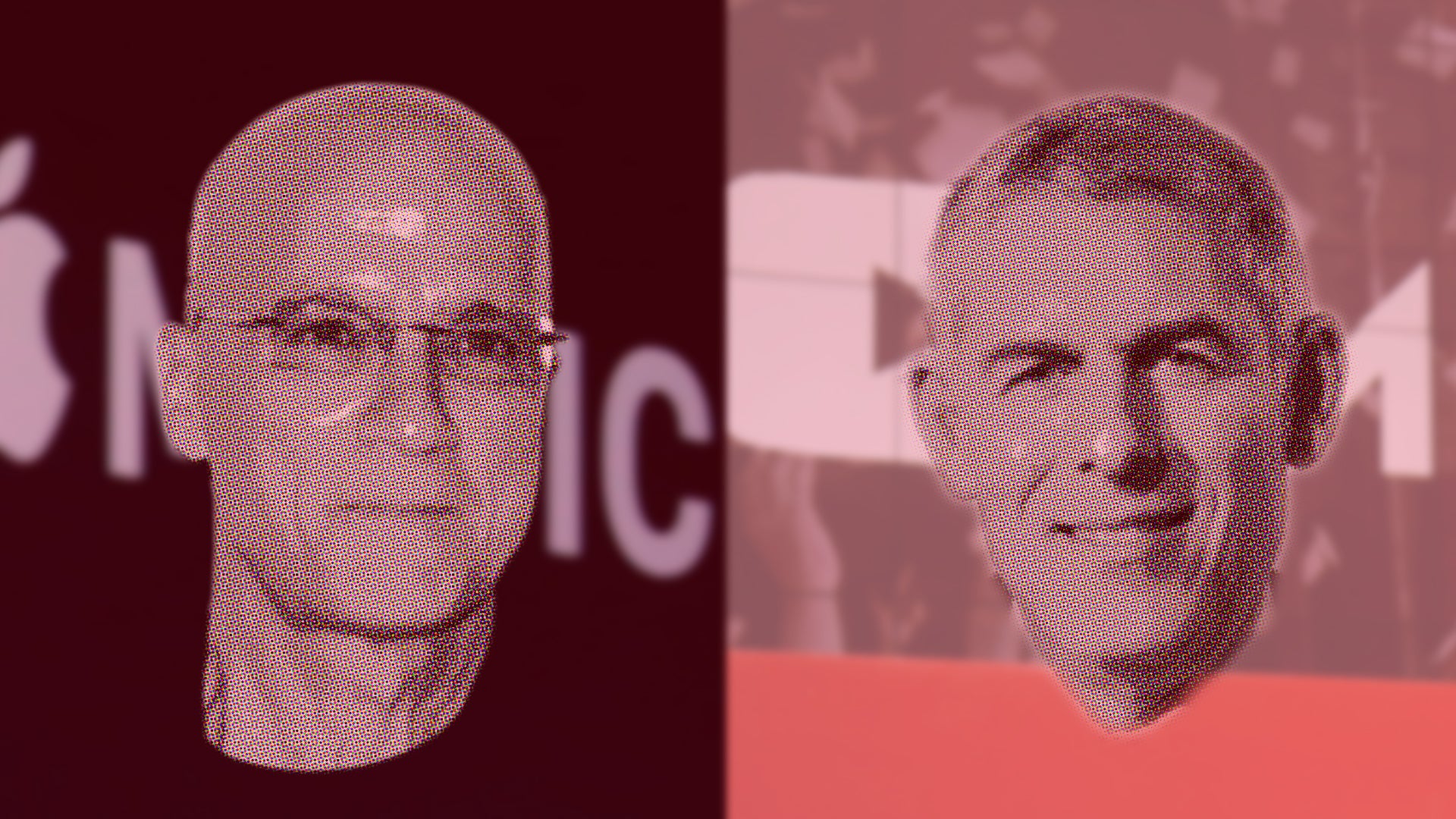

Jimmy Iovine’s name is instantly recognizable to most hardcore music fans—and not just for its oddly off-beat catchiness.

The record-producer-turned-executive began his career as a recording engineer back in the 1970s, occasionally getting to work with acts like Bruce Springsteen, Patti Smith, and John Lennon. He collected enough cred to eventually found the label Interscope Records in 1990, which was about to go under until it decided to release an album by a small-time producer named Dr. Dre. Soon, Interscope would have acts like Snoop Doggy Dogg and Tupac Shakur on its books.

Along the way, the words “Jimmy Iovine” became somewhat synonymous with the music industry itself. (In 2012, Macklemore and Ryan Lewis recorded a song about record labels and artist exploitation that was literally titled ”Jimmy Iovine.”)

But Iovine didn’t sit contently as the head of Interscope, watching the traditional industry’s profits crumble. In 2008, Iovine made his next big move—forming the designer headphones brand Beats with Dr. Dre, selling oversized headphones when minimal earphones were the trend.

Beats, by selling its products as trendy fashion statements, promptly took over nearly half of the entire headphone industry’s market share, and it also pushed into the online music space in 2013. Then, the company—headphones and nascent streaming service and all—was swallowed up by Apple in 2014 in its biggest-ever acquisition.

And that’s when Iovine took his most significant career leap.

Apple didn’t just snag a headphones business; the tech giant scored Iovine’s special knack for making smart bets in the business as a whole. For it was years prior—way before Beats was even put together—that Iovine had already started trying to convince Apple founder Steve Jobs to move into the relatively new field of all-you-can-eat music streaming, where players like Swedish service Spotify (but not many others) had nestled in. Said Iovine in a 2013 interview:

I was always trying to push Steve into subscription. And he wasn’t keen on it right away. [Beats co-founder] Luke Wood and I spent about three years trying to talk him into it.

Iovine’s hunch proved solid. Streaming is now the biggest revenue-driver in the US music industry, and globally, profits from digital platforms have officially overtaken physical ones for the first time. It was last summer that Apple finally took Iovine’s long-nagging advice, unveiling its own subscription streaming service Apple Music–headed, of course, by Iovine, who is now one of the company’s top executives.

He even stars in the ads:

Under the weathered mogul, the service has amassed a solid millions-strong subscriber base, a driver for the company’s future growth. It’s made exclusive artist deals, launched personalized listening features, experimented with video products, and may soon become a “hybrid” platform that “can help labels and artists and undiscovered artists” as well as serving listeners, according to vague hints from Iovine.

“We were too ambitious in the beginning—we probably put too much into it,” Iovine admitted recently in a BuzzFeed interview on Apple Music’s future. “But we’re getting there now, one foot in front of the other. And the stuff we’re creating, I don’t think anyone is gonna see coming.”

The claim isn’t necessarily as pompous as it sounds; the success of Iovine’s own abruptly swerving career, no one saw coming either.

YouTube’s new hope

Lyor Cohen, 6 ft 5 in, is a veritable giant in more ways than one.

Like Iovine, Cohen is an oft-whispered-about figure in the music industry—and also like Iovine, he started off small, only to later become an icon (or “lion,” as he’s been described by at least a handful of people in the business).

Initially working as concert promoter and road manager, then taking on a role within an artist management company, Cohen weaved his way to fame in the 1980s when he helped sign rising stars like Will Smith and A Tribe Called Quest. In brief, here are some of the knockout achievements that quickly followed:

- brokering a music deal with Adidas, which led to the birth of hip-hop sneaker culture

- putting together the massive 14-label Island Def Jam Music Group

- serving as CEO of Warner Music Group, one of the three biggest record companies in the world

- inventing the “360” record deal, where labels get a slice of all an artist’s revenues such as concerts and T-shirts

- founding 300 Entertainment, an independent, boutique, data-focused company aiming to incubate new musicians

That last venture proved the most prescient. Over the past decade, as record labels stumbled, plump tech giants like Apple and Amazon—first with inventions like iTunes, and now with streaming—have slowly slid into their place, as most recently evidenced by Frank Ocean’s flagrant defiance of Universal Music in favor of a streaming deal this fall.

Cohen—a man notorious for walking around constantly barking the question, ”Is this the cutting edge? Or is this the cutting edge?”—recognized the trend early on, and started 300 in 2012 as a mash-up of a tech company and a traditional label. There, he lured onboard acts like Young Thug and Fetty Wap, and catapulted them to fame. The company also planned an unprecedented data partnership with Twitter, aiming to use analytic tools for artist discovery.

Cohen even joined Snapchat to promote a Young Thug album—recently posting a story more fitting of his star-studded artists than of an aging entertainment mogul.

Says Cohen, who was aptly described by Complex this fall as a “no-bullshit businessman who will burn one bridge while erecting three more”:

I want people to put themselves at risk. If we’re having a meeting and you’re not saying anything, then you’re sandbagging and you’re pimping all of my effort. If you don’t have any ideas, that means you’re not willing to put yourself at risk. It takes a thousand dumb ideas to come up with one great one.

Speaking of risk: at the end of September, Cohen decided to ditch his beloved 300 and become head of music at YouTube.

Weird move? Seems like it, at first. The Google-owned video platform is reviled by (what’s left of) the traditional music business that Cohen used to run. Record labels accuses the site of all but intentionally stealing money from artists. But YouTube has big plans for music, having just launched its streaming subscription service YouTube Red. Cohen’s hire—which surely didn’t come cheap—suggests the platform is willing to go all in.

On Cohen’s end, there’s also immense faith in that plan. In an explanation to 300’s employees for his departure, he noted how technology and new formats of music-listening ”have completely changed the established distribution channel,” and expressed excitement at the untapped potential in that area. His initiatives at YouTube will no doubt be watched closely by figures both inside and outside the music industry.

Today’s music business is a completely unrecognizable beast from what it was a decade ago—yet Iovine and Cohen have clung to the top with a tenacity that no other industry undergoing such a shake-up has ever seen.

From the start, Iovine and Cohen built their careers on the risky, fledgling music genre of hip-hop. Both embraced the advent of digital music—a concept that many other label executives, in panic, decided to blindly ignore—and championed the idea of on-demand entertainment. Both are now working with one foot in the old music business, the other firmly planted in Silicon Valley.

Recounting the swerving course of his professional career at a commencement address in 2013, Iovine told the University of Southern California’s graduating class: “Fear, at times, makes us protect and defend what we think we already know. But sometimes in life you need to learn a new lesson.” New lessons are exactly the music business—perhaps also the entertainment industry at large—is all about these days.

And Iovine and Cohen’s former record label buddies seem to be catching onto the trend. The brain drain of label executives to tech-based music companies in recent months has been massive: All three of the world’s major labels (Sony, Universal, Warner) have seen big players leave for Spotify and its peers.

Even Napster, which is still around, got a new CEO this summer—and he’s a former executive from Universal.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Iovine left Interscope to form Beats in 2008.