Uber is looking for its Sheryl Sandberg

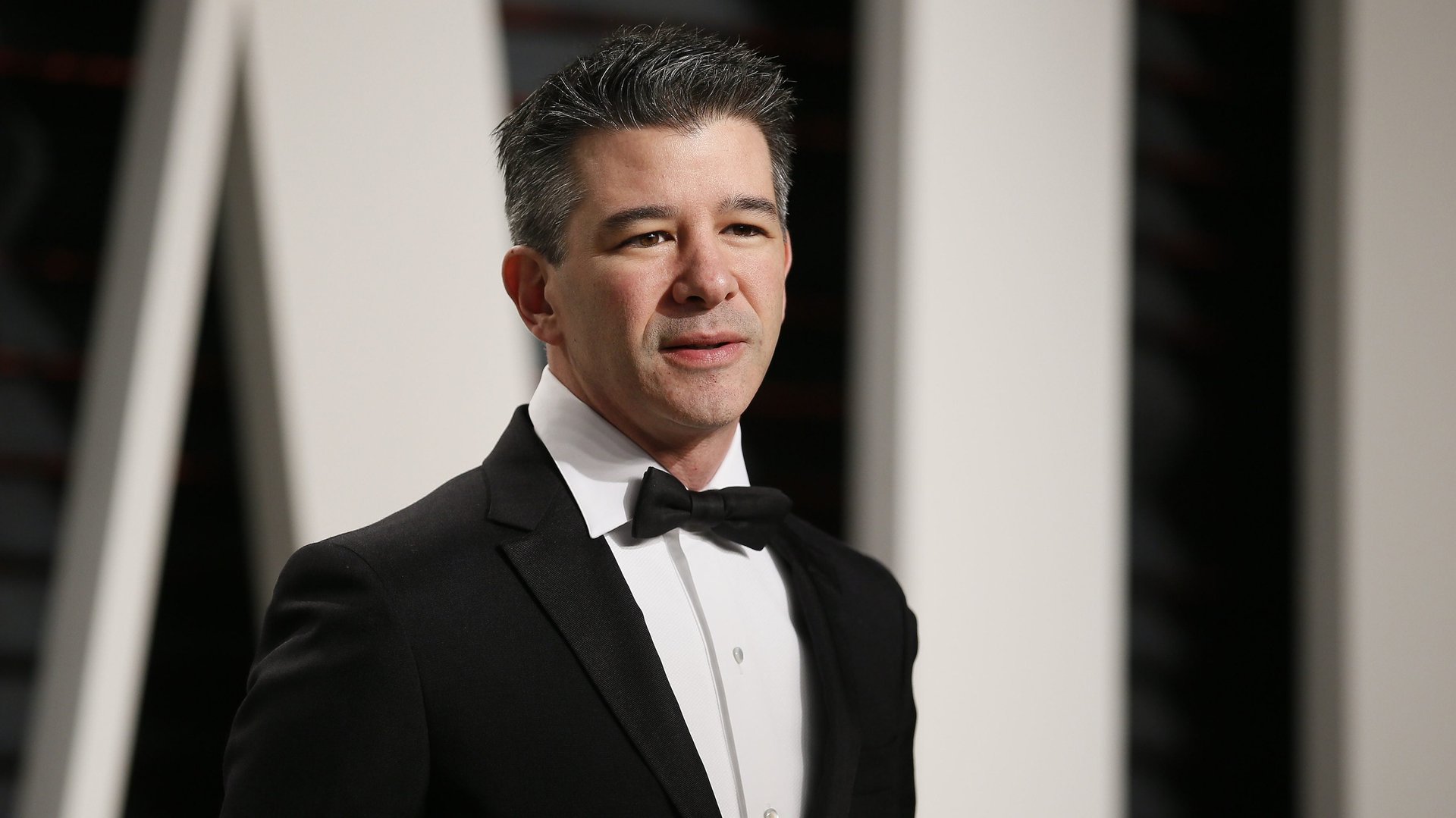

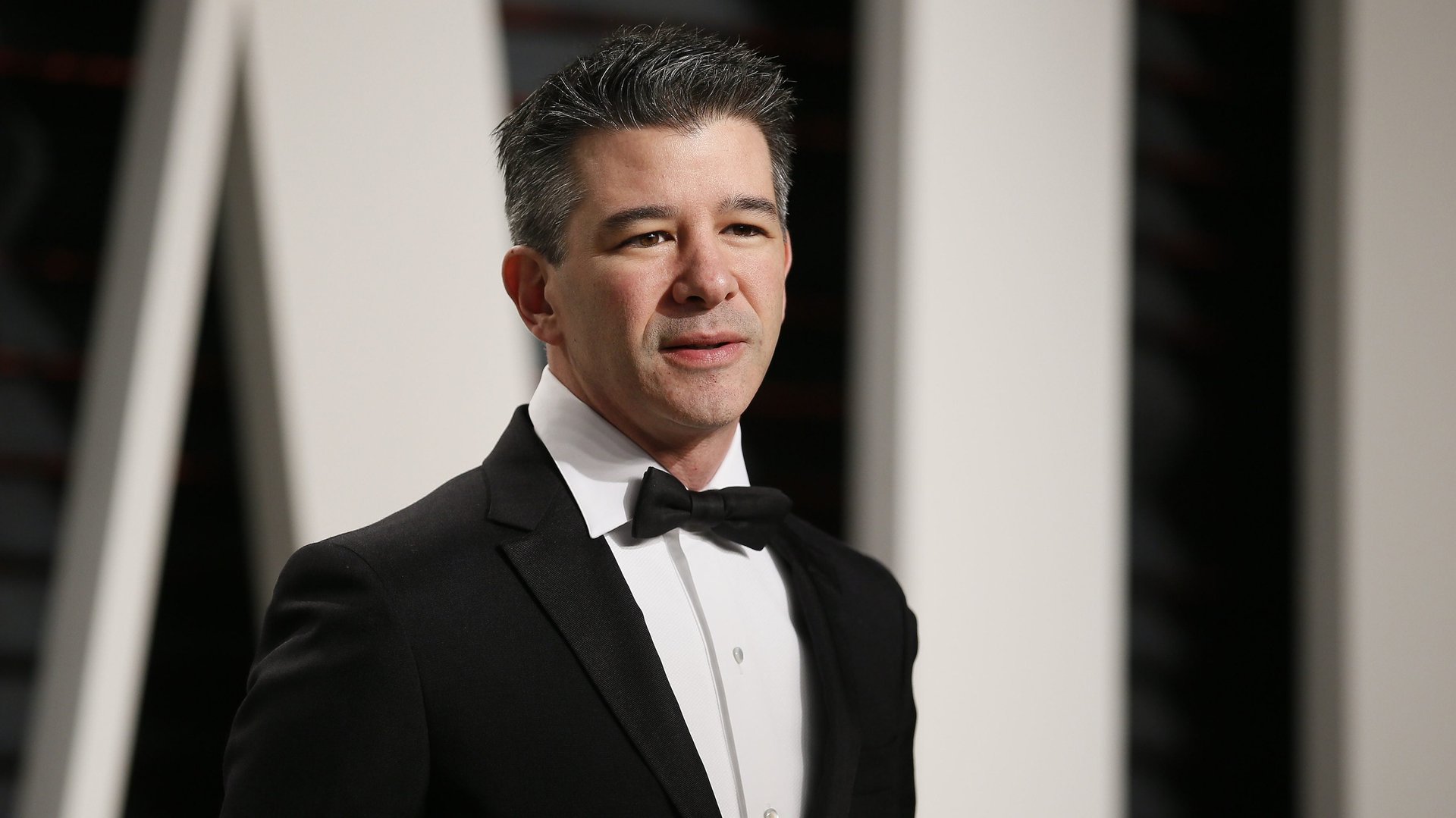

“I must fundamentally change as a leader and grow up,” Uber CEO Travis Kalanick told the world on Feb. 28, after dash-cam footage showed him berating one of the company’s own drivers. ”This is the first time I’ve been willing to admit that I need leadership help and I intend to get it.”

“I must fundamentally change as a leader and grow up,” Uber CEO Travis Kalanick told the world on Feb. 28, after dash-cam footage showed him berating one of the company’s own drivers. ”This is the first time I’ve been willing to admit that I need leadership help and I intend to get it.”

On March 7, Kalanick shared a bit more, telling staff that Uber is “actively looking” for a chief operating officer—“a peer who can partner with me to write the next chapter in our journey.”

It’s not unlike what Facebook did in 2008, when it brought in Sheryl Sandberg from Google to work with company founder Mark Zuckerberg. That decision, made four years before Facebook went public, proved wildly successful for Facebook. But the move doesn’t always pan out. Snapchat co-founder and CEO Evan Spiegel has burned through several more experienced managers, including Emily White, a well-regarded Silicon Valley exec who left her post as COO in March 2015.

Uber’s new COO will have his or her work cut out, and not just in terms of handling Kalanick.

The company is trying to regroup from a recent, explosive account of sexual harassment alleged by a former engineer, reports of an unrestrained and Machiavellian culture, and turnover in its executive ranks. In the last two weeks alone, Uber has fired its SVP of engineering over undisclosed sexual harassment allegations from his time at Google) and bid farewell to Ed Baker, its VP of product and growth.

Those are just the most recent troubles. Uber has broken laws, attacked politicians, offended cities, invaded user privacy, and nurtured decidedly hostile relationships with many of its drivers. (Jeff Jones, a former marketing executive at Target who joined Uber last summer as president of ride-sharing, has so far failed to smooth things over with the driver community.)

Kalanick, for his part, may have stopped saying “hashtag winning” and “Boob-er” in public, but the video of him confronting an Uber driver suggests he remains prone to outbursts in private.

Kalanick has likely been reluctant to seek leadership help because doing so could dilute his near-total control of Uber. He and two of his closest alies—Uber co-founder Garrett Camp and former CEO Ryan Graves—have a majority of shareholder voting power, tech news site The Information reported this weekend. That means they effectively control his fate as CEO.

Within the company, meanwhile, Kalanick’s influence is everywhere: in Uber’s zero-sum meritocracy, its disdain for authority, and willingness to shirk the law. Employees don’t question it. As one told The Information a year ago when asked if Uber had a no. 2, “Yes. It’s Travis.”