The American mercenary behind Blackwater is helping China establish the new Silk Road

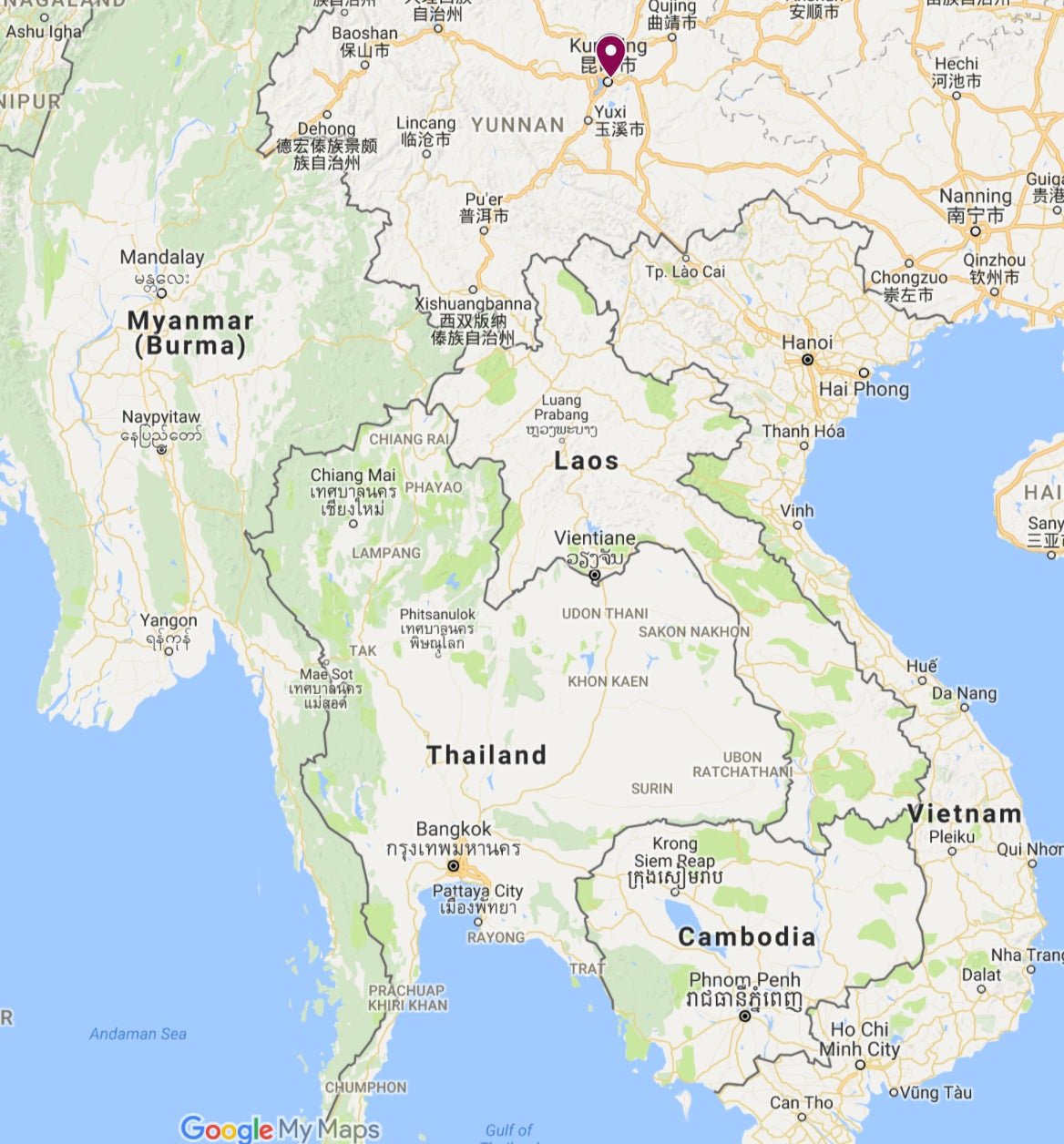

For years, China has groomed landlocked Yunnan province in its southwest to be the country’s strategic bridgehead into Southeast Asia, building highways and rail lines to its borders with Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar to one day weave them into a regional, and eventually, transcontinental transport network.

For years, China has groomed landlocked Yunnan province in its southwest to be the country’s strategic bridgehead into Southeast Asia, building highways and rail lines to its borders with Vietnam, Laos, and Myanmar to one day weave them into a regional, and eventually, transcontinental transport network.

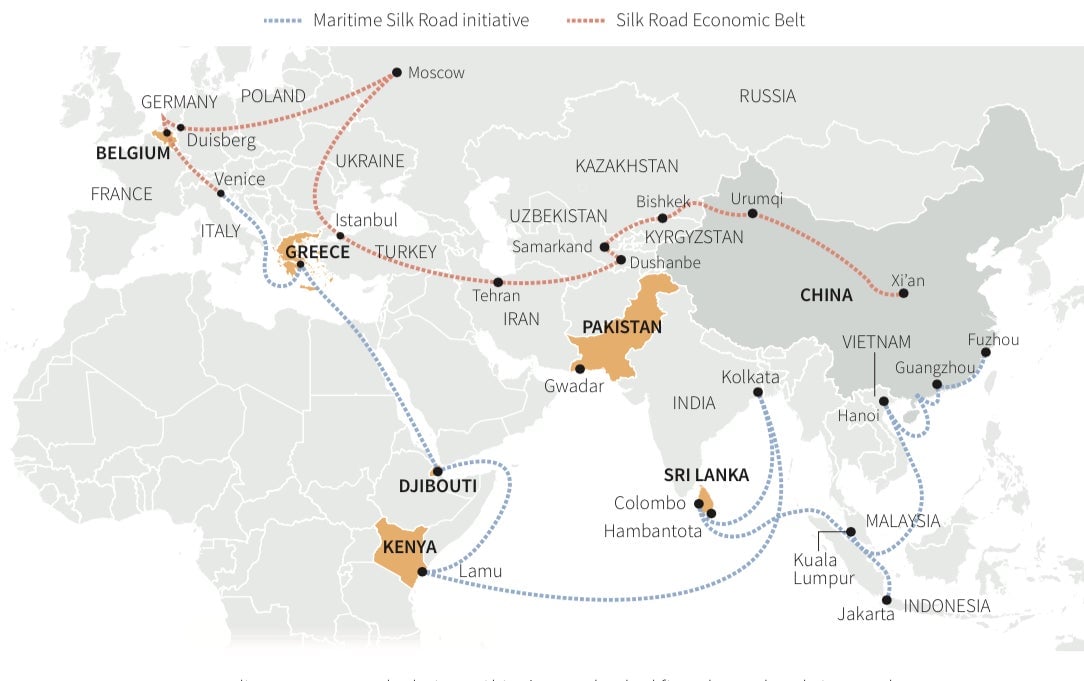

As China pushes ahead with president Xi Jinping’s ambitious $1 trillion One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative—which reimagines a historic trade network as an overland Silk Road Economic “Belt” and a Maritime Silk “Road”—protecting Chinese business executives and other personnel and their rapidly growing investments in the region is more important than ever.

Enter Erik Prince.

Prince, a former US Navy Seal, is best known for founding the armed security services firm formerly known as Blackwater, whose employees were found guilty for the killing of 17 unarmed Iraqis in Baghdad in 2007. After selling Blackwater in 2010 and relocating to Abu Dhabi—where he reportedly set up a mercenary force (paywall) for the government—Prince has turned his sights on China.

He is now chairman of Frontier Services Group (FSG), which announced in December that it is setting up a “forward operating base” in Yunnan to provide logistics and unarmed security training services to facilitate OBOR-related projects in Southeast Asia. Just as he positioned himself to profit from George W. Bush’s military adventurism in Iraq more than a decade ago, he is poised to benefit from this decade’s dominant theme: a global realignment around China’s economy.

Yunnan is a natural link between China and its Southeast Asian neighbors. Located on the fringe of imperial China until its absorption by the Ming Dynasty in the late 14th century, the mountainous province, roughly the size of California, was historically home to kingdoms and trade networks that extended deep into these countries’ present territories. Many of Yunnan’s two-dozen ethnic groups, such as the Jingpo, Dai, Wa, and Miao, can be found in the highlands of its neighbors, and it is the source of the headwaters of Southeast Asia’s most important rivers, the Mekong and Salween.

Powerful partners

Prince’s Washington connections, cultivated via his time in the military and his wealthy, well-connected family—he is the brother of US education secretary Betsy DeVos—were helpful to Blackwater in securing an estimated $2 billion in contracts, primarily in Iraq and Afghanistan. Similarly, through FSG, he is tightly connected to China’s state-owned conglomerate CITIC Group, which owns 20% of the company and was ranked 156th on Fortune’s Global 500 list last year. CITIC has major subsidiaries involved in banking, securities, construction, real estate, technology, and more. Prince has denied that he’s gone from being Washington’s favorite mercenary to a Chinese gun-for-hire.

“We’re not serving Chinese foreign policy goals,” Prince told the Financial Times (paywall) in a March interview. “We’re helping increase trade.” FSG told Quartz. Prince was unavailable to comment for this piece.

CITIC has a major presence on FSG’s board of directors too. Both FSG chairman Hu Qinggang and deputy chairman Luo Ning have close ties to CITIC Group—Hu was previously its financial director and Luo is currently an assistant president at CITIC Group and sits on the boards of several of its subsidiaries. CITIC is also one of the biggest players in the OBOR initiative; less than two years ago, the group said it would invest more than $100 billion in OBOR-related projects.

CITIC did not respond to a request for comment.

Incorporated in Bermuda and listed in Hong Kong, FSG first began working with Chinese corporate clients in Africa—another OBOR destination—where Chinese investment has ballooned in the past decade.

The fact that FSG is being allowed to set up a “base” in Yunnan suggests a strong degree of trust in the company from the highest levels of Chinese leadership. What’s more, the company is also planning on expanding into the highly militarized region of Xinjiang afterward to facilitate OBOR projects in Central Asia.

Resource-rich Xinjiang, which is majority Muslim, has been on the receiving end of increasingly repressive Chinese rule in recent years, including months of blocked or limited internet service, and more recently, a ban on beards and veils. Beijing says such measures are necessary to counter growing Islamic extremism in the vast region, while critics contend that Beijing is fueling extremism through its repression.

Location, location, location

Continental Southeast Asia has natural resources, low labor costs, and growing consumer markets, but it also has something that China lacks: access to the Indian Ocean. By building up Yunnan’s connectivity to this region, it effectively creates a backdoor for goods leaving and entering China’s west, saving time and money.

“A top priority for OBOR is to establish linkages to ports in Myanmar and Thailand that significantly cut costs of shipping goods to Europe and Africa,” said Brian Eyler, director of the Southeast Asia program at the Washington DC-based think tank Stimson Center, who lived in Yunnan for five years and has been researching its relationship with neighboring countries for more than a decade.

The Indian Ocean also offers strategic value as a corridor that bypasses the Malacca Strait, which China fears could be closed off by the US during a conflict.

An oil pipeline connecting the Myanmar coast with a new refinery in Yunnan’s capital, Kunming, went into operation last week, after Xi met with Myanmar president Htin Kyaw in Beijing. The pipeline allows crude oil from the Middle East and Africa to flow directly into China’s energy-thirsty southwest provinces. A parallel gas pipeline has been operating since 2013, and last year delivered 5% of China’s imported natural gas.

How big a role FSG will play in China’s OBOR plans for Southeast Asia is still unclear, but its partner CITIC is already heavily involved in the region. CITIC leads two consortia developing a deep sea port and a special economic zone in Myanmar, at the western end of the pipelines. The twin pipelines show how OBOR-related projects can reshape the region, but they also highlight the risks in China’s growing investments in its Southeast Asian neighbors.

One bumpy road

Anti-Chinese sentiment in Southeast Asia is one potential flashpoint. In Myanmar, the aforementioned pipelines, as well as the stalled $3.6 billion Myitsone dam project and a controversial copper mine allegedly linked to human rights abuses—all Chinese projects inked with the junta that once ruled the country—are deeply unpopular. The pipelines and proposed dam are especially unwelcome to many Myanmar people because they almost exclusively benefit China.

Nor are protests over environmentally destructive Chinese-built infrastructure projects, and Chinese investment more broadly, confined to Myanmar. Local populations from Vientiane to Phnom Penh (paywall) to Bangkok increasingly worry that their countries are becoming Chinese vassal states.

The 2011 suspension of the Myitsone dam project by Myanmar’s then-president Thein Sein may have been a turning point for China’s leadership. Beijing, which previously only cared about government-to-government relations, started building schools and hospitals. China also reshuffled Yunnan’s political leadership in the following years, with those who supported policies and projects that left a poor environmental or social record in neighboring countries sidelined, said Eyler. “The new leadership seeks to implement protocols to promote higher degrees of inclusiveness and more sustainable environmental approaches,” he added.

However, he noted, the results of these new approaches have yet to be seen, and reining in the diffuse set of Chinese investors and interests working in mainland Southeast Asia is no easy task.

Risky business

Within this context, it is understandable that security would be a growing concern for Beijing. FSG’s first move in Yunnan will be to open a Kunming office this year, with the possibility of additional facilities elsewhere in the province, according to a company spokesman.

The company intends to “provide an operations facility where we can integrate ground and air logistics together with a training facility,” the spokesman said, adding that all services will be unarmed and that “details of the training services are still under discussion.”

FSG will not hire or train any active duty military personnel, but also “does not discriminate based on a potential applicant’s background,” he said.

Setting up in Yunnan could leave FSG and Prince well-positioned to benefit from China’s numerous big deals in neighboring countries—more of which may be unveiled at next month’s two-day OBOR forum in Beijing. Announced by president Xi at the most recent World Economic Forum in Davos, the gathering is likely to be viewed as yet another globalist feather in Xi’s cap, while the Trump administration confounds Europe, bombs the Middle East, and sends tremors of uncertainty down East Asia’s political fault lines.

It remains to be seen if Prince will replicate Blackwater’s financial success with FSG in China, but the main ingredients of connections, money, and policy appear to be in place, as does demand. As Eyler sees it, “Yunnan continues to be a critical conduit for outbound Chinese investment and power projection to the region.”