Greece, although it’s shown some signs of drawing foreign investment, is still in pretty awful shape. And it’s gotten even worse today; yields on government bonds jumped 80 basis points, after new concerns about the country’s political stability.

Greece’s ruling coalition just lost one of its partners, the Democratic Left, after a dispute about shuttering the country’s public broadcaster, ERT. Struggling to meet the terms of economic reforms, Greece’s government now threatens to upset its fragile political balance.

Not to mention that the IMF is now giving euro zone leaders an ultimatum, which the Financial Times reported yesterday (paywall): If they can’t come up with €3-4 billion ($4-6.6 billion) to meet a funding shortfall in Greece’s €172 billion plan by next month, then the fund will suspend its own aid payments.

But some of the burden for the missing cash could end up on Greece’s shoulders. With that in mind, “political instability is the last thing that Greece needs at present,” says Citi FX analyst Valentin Marinov.

Even beyond the headlines, however, Greece is in bad shape. Economic reforms handed down by the troika—the IMF, the European Central Bank, and representatives from European countries—have destroyed the country’s economy with the hopes of one day making it more competitive. One day far, far in the future.

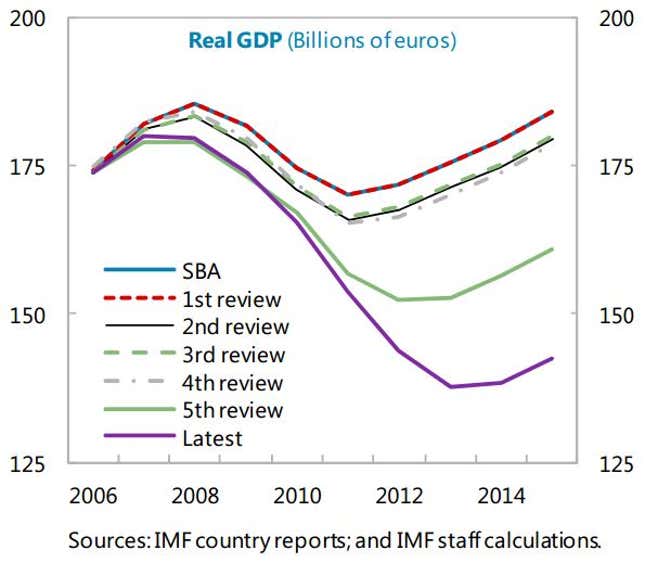

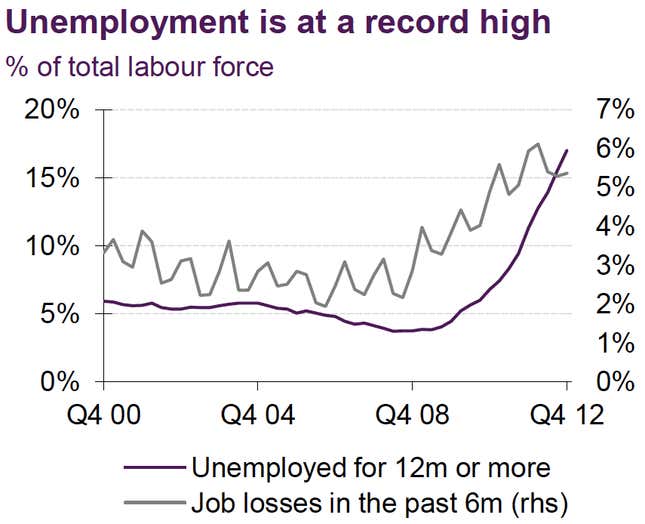

Greece’s recession has now lasted 5.5 years, something the troika never expected. In fact, the IMF’s projections show that euro zone policymakers have consistently underestimated the severity of the Greek crisis. More and more people are still losing their jobs.

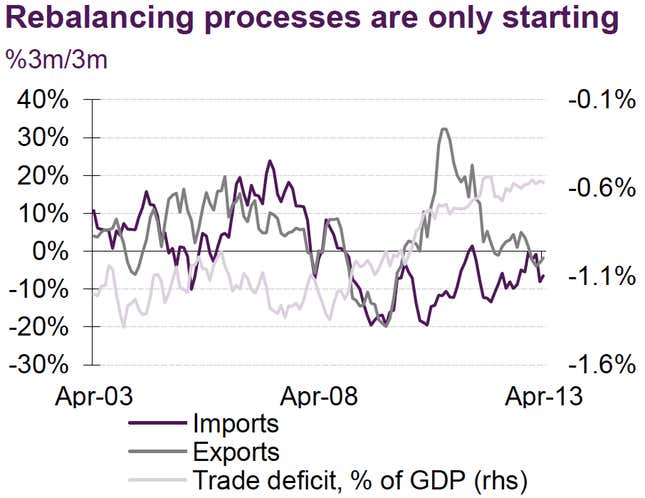

Wages and prices have only just begun to rebalance. Prices have only begun to fall in 2013—a process that isn’t proceeding smoothly—and lower wages haven’t helped the country produce more exports. That’s partly because the people who would buy those exports are neighbors to the North, most of whom are suffering from their own recessions.

Greece’s leadership is in a vulnerable position. Parliamentary elections had to be held twice in 2012 because leaders could not form a coalition, and the anti-establishment SYRIZA party. Today, the opposition, which would hold a referendum on the euro and renege on its commitments to the troika, trails the leading New Democracy party by a razor-thin margin.

Though the Democratic Left isn’t a big party (just 17 seats in a 300-member parliament), the departure weakens the governing coalition. “The political backdrop is now set to become more unstable, thereby increasing the risk of early elections in the medium term (Q4 onwards),” Teneo Intelligence analyst Wolfango Piccoli wrote in a client note today.

This makes it difficult to believe euro zone leaders’ forecasts of impending “grecovery.” In the last year, Greece has provided a great opportunity for investors willing to take on risk and speculate in fixed income. But the window of opportunity may be closing.