This June, it’s exactly 50 years since the Beatles dropped Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—a seminal album that shaped its time. As Rolling Stone magazine writer Langdon Winner put it:

The closest Western civilization has ever to unity since the Congress of Vienna in 1815 was the week the Sgt. Pepper album was released. In every city in Europe and America, the radio stations played [it], and everybody listened.

For a brief while, the irreparable fragmented consciousness of the West was unified, at least in the minds of the young.

Even with all the other musical icons around in the mid-1960s—The Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan would top many rock fans’ lists, The Beach Boys for pure pop, and Otis Redding and The Supremes for soul—it isn’t hyperbole to say that the Beatles all but ruled the cultural landscape of those years. Sgt. Pepper seemed to strum out the restless iconoclasm of an entire generation, with tracks like “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” managing to both illustrate and define the collective mood of people all over.

Because heading to a local record shop to snatch up the latest hits on vinyl LP was the only way for listeners to buy music in that time, album sales could be tracked, in orderly fashion, and the Beatles’ dominance of the age can be seen right in the charts. It’s clear in the numbers—the Beatles hold a plethora of singles records, and the band still ranks as the best-selling artist ever.

A couple of decades later, though, that tidy system of sales-tracking has gone haywire. For example, who was the biggest artist of 2016? Well, don’t ask Adele, who won album of the year at the 59th Grammy Awards in Los Angeles this year—as conclusive a title as any—and protested it.

“I can’t possibly accept this award,” the British pop star declared on the Grammy stage in February, theatrically snapping the gold statue in her hands in half. She went on: “My artist, of my life, is Beyoncé.” Meanwhile, Beyoncé herself took home the Grammy for best urban contemporary album, a wacky category that lacks any real definition but seems to serve as a consolation prize for artists who don’t place in the big leagues. (Adele, after Kanye-ing herself, did end up accepting the award.)

Music criticism like Winner’s is subjective, governed by personal tastes. But if the academy can’t settle the question of which artists are the biggest of their time, then surely, the charts can? Yet there, too, things are muddied. Thanks to a total fragmentation of music-listening methods, music charts—once the reliable last word on the talent or at least popularity of an artist—also don’t have the answer. First came online platforms like Napster and iTunes in the 2000s, introducing individual songs for digital download; music “sales” scattered even further once buffet-style streaming services like Spotify, Soundcloud, and Apple Music arrived.

Now, being the artist of the year is really anybody’s—and everybody’s—game.

If we look at America’s top albums of 2016 as tracked by Nielsen Music, the data analytics company that performs multi-metric US entertainment consumption tracking, we see the boggling problem in action.

* 1,500 track streams are counted as one unit.

** 10 track sales are counted as one unit.

Per total “units” sold and streamed, the biggest artist of 2016 was actually Drake. But note that most of what made him so big were streams.

Nielsen used to only consider pure album sales towards an artist’s ranking, but it redefined the formula in recent years to take newer platforms like streaming into account. Now, one physical or digital album sale is tallied the same way as 10 individual track sales or 1,500 song streams—a somewhat arbitrary equivalence that has led many people to realize that the system can be gamed. Case in point: Devotees of pop star Harry Styles recently circulated tips on how to boost the singer’s rank in the charts, such as downloading a VPN from other countries to count song streams toward his US rank, and Future, a prolific rapper, became the first artist to knock his own album out of the #1 spot with another new album. Because of the helter-skelter way music sales get tallied, Future’s accomplishment was at once absurd, impressive, and meaningless.

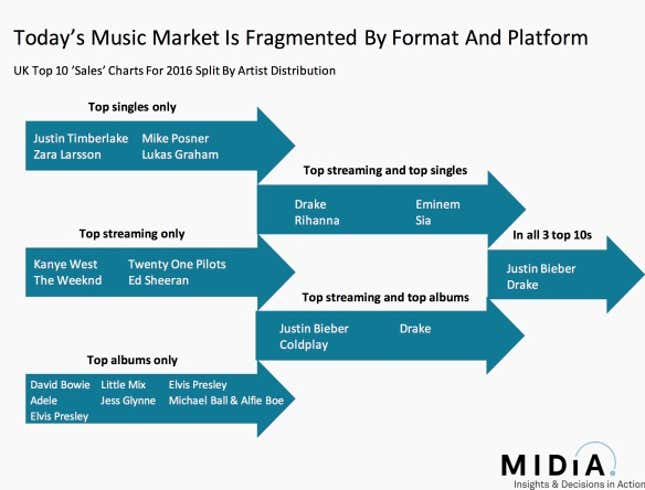

“One size stopped fitting all long ago,” says music industry analyst Mark Mulligan. “Now there are clearly two broad groups of music audiences which must be addressed in entirely different ways, across different channels and with different tactics.” Mulligan means the divide between the streaming generation and people who grew up having to buy physical music, many of whom are still unaccustomed to the new model of leasing giant catalogs of songs for a set monthly fee.

Going by actual sales, Adele holds the designation of biggest artist of the year. Yet if we look primarily at how many times people buy artists’ singles or individual tracks, Beyoncé and Rihanna are actually much more popular.

At the beginning of 2017, on-demand streaming services surpassed digital music sales for the first time in history, growing 76% in the US. Dominating streaming charts are the fast-growing genres of hip hop and R&B. It was Drake, Rihanna, Kanye West, and The Weeknd who produced the most-streamed songs of last year, regularly plopping fresh tracks onto the likes of Spotify, Apple Music, and other subscription services. This skewing of genre makes sense: The bulk of streaming’s audience tends to be young and tech-savvy, and research shows that every generation of music listeners has a different sound; it would seem that a mash-up of hip-hop/R&B/rap is shaping up to be the dominant genre of today’s young adults.

It also means different generations—and their preferred sounds—are living on entirely divergent platforms, rarely overlapping, and making it ludicrous to try and declare a single biggest artist, or even five, of the age. Adele—said to jive the most with older, “diaper-changing, lunch-packing” women—governs an entirely different audience to Drake and his young streaming-generation fans, or Rihanna and her fervent clan of social media lovers.

Even if the data makes it so, a mother buying one Adele CD cannot be genuinely compared to her daughter streaming Jay Z’s songs 1,500 times on an iPhone. Then there’s the question of how to count people who are ordering special-release vinyl LPs or freeloading music off of YouTube. Add in the critics’ picky musings (Kendrick Lamar is king, say the current majority), and you’ve got total cacophony—a reflection on just how little sense the charts make anymore. For let’s not forget who the winner of 2016 in terms of the physical-only album sales. Justin Bieber? Ed Sheeran?

No. Mozart.

As the northern hemisphere starts to warm up and more people press play on new pop tracks, entertainment publications love to speculate on the ”song of summer.” Replace “summer” with “year,” “decade,” et cetera, and you’ll find hundreds of the same story. It is an utterly misleading one.

The collective audience of the glorious Sgt. Pepper time has now been forever scattered, with music fans shooting off to various listening methods in every direction; even radio is less reflective of an artist’s rank than of his or her marketing potential. The next time somebody tries to claim this or that musician is the biggest of the time, all you can possibly do is take their word for it.