A legal tussle over a strategic African port sets up a challenge for China’s Belt and Road plan

It’s been exactly a year since the Dubai-based port operator DP World accused Djibouti of illegally seizing control of the Doraleh Container Terminal (DCT) it operated in the northeast African country. The move triggered denunciation from Emirati officials, kick-started a succession of legal battles that have spanned the globe, and brought into focus China’s deepening role in the Horn of Africa.

It’s been exactly a year since the Dubai-based port operator DP World accused Djibouti of illegally seizing control of the Doraleh Container Terminal (DCT) it operated in the northeast African country. The move triggered denunciation from Emirati officials, kick-started a succession of legal battles that have spanned the globe, and brought into focus China’s deepening role in the Horn of Africa.

It all started in 2004 when DP World signed a 30-year concession agreement with Djibouti to exclusively design, build and manage the geo-strategic terminal. But right from the commencement of operations in 2006, relations between the two sides became fractious, with officials in the tiny African state campaigning to renegotiate the terms of the deal. In 2012, Djibouti accused the global ports operator of paying bribes to secure the deal, and launched an arbitration case in London after out-of-court negotiations fell apart.

Then in 2013, Djibouti sold 23.5% of its 66.66% stake in the Doraleh Terminal to China Merchants Port Holdings (CMP), the Hong Kong-based subsidiary of the state-owned conglomerate China Merchants Group. This was a move that didn’t sit well with Dubai’s DP World, which still owned the remaining 33.34% of the terminal.

Djiboutian officials claim the concession agreement contravenes state sovereignty and national interests and makes DP World the key authority in a geo-strategic corridor. Even though Djibouti held the majority of the equity on the port, DP World, they say, held a majority of the voting rights on the board of directors.

Dubai, they also argued, was conducting a game plan that protected its own Jebel Ali port, and was preventing Djibouti from developing into a fully-fledged and versatile shipping hub. Its involvement in other ports along the Red Sea, namely in Berbera in Somaliland and Jeddah in Saudi Arabia, also meant it was developing competitors to the Doraleh terminal. The concession also gave DP World the rights to develop new ports, which is why China’s construction of the Doraleh Multipurpose Port that opened in mid-2017 escalated the situation further.

Following heated discussions between the two parties, Djibouti on Feb. 22, 2018 terminated the contract with DP World through a presidential decree and expropriated all assets at the port. In September, it nationalized the state port company’s stake in Doraleh, effectively taking Doraleh out of commercial hands and undermining the Dubai shipping company’s future in the Horn.

The fallout from these battles was first adjudicated in the UK last August, where a tribunal stated the contract with DP World remained “valid and binding.” That was followed by a decision from the High Court of England & Wales in September that granted an injunction prohibiting Djibouti from terminating the joint venture.

In November, DP World sued China Merchants in Hong Kong for bypassing its concession agreement with Djibouti and acquiring an indirect shareholding in the Doraleh terminal. Besides the multipurpose port, China Merchants has also built a free trade zone and has promised to revamp the Djibouti port into a global modern facility. DP World says it has the right to seek legal action, including damages for claims from third parties that violate its contractual rights.

Djiboutian authorities contend they have tried to resolve the issue amicably but remain obdurate in their decision to “break the monopoly” of DP World. “You cannot have or run the country as a company,” says Aboubaker Omar Hadi, the president of the Djibouti port authority. “We control our assets. We are a very small country. We are very jealous in keeping our assets.”

Djibouti’s geographic location is pivotal given its close proximity to key nations in both Africa and Asia, as well as being a crucial route for global shipping, especially those heading to the Suez Canal in Egypt.

During talks in January 2018, Aboubaker says he urged DP World’s chairman Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem “don’t break the deal.” Calling the Hong Kong case “complete nonsense” and “a waste of time and resources,” he said DP World shouldn’t fight them in court but come back to the negotiating table. “If they want to discuss, they are welcome.”

Murky affair

On a basic level, the fight over Doraleh pits two state-backed conglomerates against each other. Jointly they have operations in over three dozen nations across six continents. But on a higher level, the case in Hong Kong presents one of the first legal challenges to China’s globe-spanning, trillion-dollar Belt and Road initiative. In recent years, Beijing has shored up maritime investment along the Indo-Pacific regions, building ports to extend its market reach and its geo-strategic sea power.

The fact that the case will be thrashed out in Beijing’s own backyard is also likely a blow, especially as China-led projects face scrutiny in nations like Kenya and Ghana or get canceled like those in Pakistan, Myanmar, Nepal, and Malaysia.

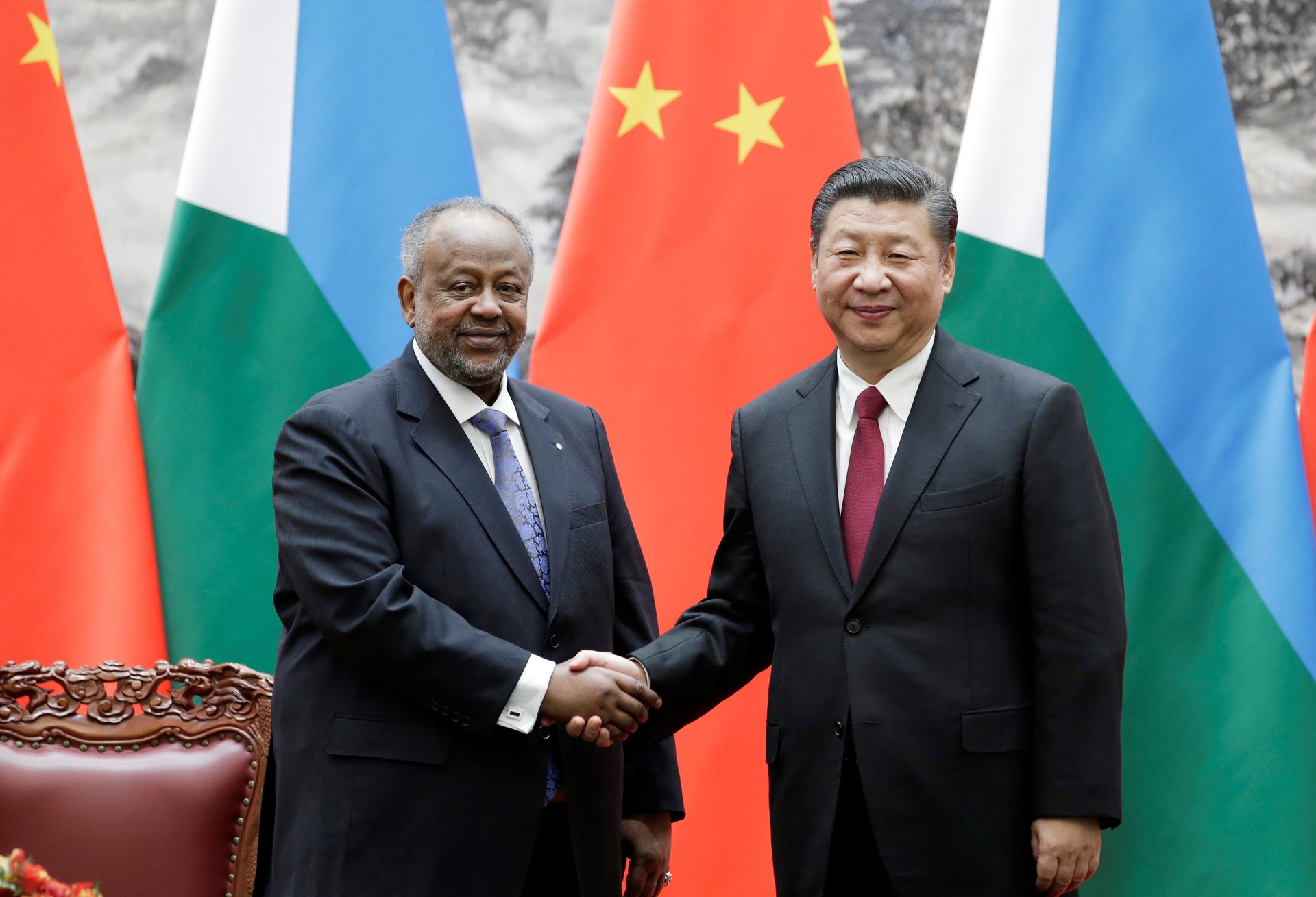

China’s deepening reach in Djibouti also comes amid increasing questions over the economic viability and the geopolitical intentions of its investments. Besides building its first overseas military base in Djibouti, China has financed a railway line linking the capital Djibouti to Addis Ababa, built a 63-mile long pipeline to supply safe drinking water, offered to mediate the Djibouti-Eritrea border row, and has participated in anti-piracy patrols in the region.

Chinese financiers also hold 77% of Djibouti’s debt, raising concerns on whether new and future projects could generate sufficient revenues to meet debt service requirements.

“It’s a worrying situation,” says Daher Ahmed Farah, who heads the Djiboutian opposition party Movement for Democratic Renewal and Development. Struggling to pay its debt to Chinese firms, Sri Lanka in 2017 handed over its major Hambantota port to China Merchants, the same firm developing Djibouti’s ports. If a similar scenario unfolds, it could prove ominous for the micro-state with barely a million people, Daher explains. “This is where we don’t want to end up.”

Internal struggle

Given the legal wrangle, DP World finds itself “on the wrong side of a quarrel among Djibouti elites,” says Jordan Link, research manager at the China-Africa Research Initiative at the John Hopkins University.

For years, Djibouti has sued Abdourahman Boreh, a former confidante of president Ismail Omar Guelleh largely considered the architect of the concession agreement with DP World. Yet the cases have been dismissed by London courts, with Boreh alleging he was targeted for refusing to back a constitutional amendment that would guarantee president Guelleh extend his time in office.

Since coming to power in 1999, Guelleh has been re-elected four times and has solidified his rule over the former French colony. The 72-year-old has also made the country an attractive spot for foreign powers to set up their navy and military bases including those from France, China, and the United States.

And with the war in Yemen, the geostrategic importance of the Red Sea corridor has become even more prominent says Elizabeth Dickinson, senior analyst for the Arabian Peninsula with the International Crisis Group. Given the rise of the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels around the Bab al-Mandeb Strait, the United Arab Emirates in 2015 sought a naval and air base from which to strike against them. After Abu Dhabi tried using DP World’s infrastructure as a launching pad, relations with Djibouti soured, according to a 2018 report from ICG.

This pushed the Emiratis, and their Saudi allies, to seek out a military base in Assab, Eritrea—stirring up tension between Asmara and Djibouti, who already had a restive past.

The “disregard to local dynamics,” Dickinson argues, “can only serve the cause of instability” in the Horn of Africa.

Broken relations

It’s not yet clear how the ruling in Hong Kong might differ from those in the UK, how the Djiboutian government might respond, or if a decision favoring DP World would be implemented in Djibouti. But as challenges involving commercial interests and state sovereignty unfold along the Maritime Silk Road, it might boost Beijing’s plans to establish special courts dedicated to settling the disputes.

If DP World wins in Hong Kong, Link says “this will, of course, hurt the reputation of China Merchant’s Port, a growing rival of DP World.”

Dickinson says there are enough opportunities for multiple ports to prosper in the Horn, which is underserved for container ship capacity. And while the Djibouti port remains a class above the rest, for now, she says she doesn’t see the upcoming court case as changing the already-strained UAE-Djibouti relations. “What has been lost is already gone, and that is trust.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox