For Ethiopian Airlines, Mar. 10, 2019, will forever be a day to remember.

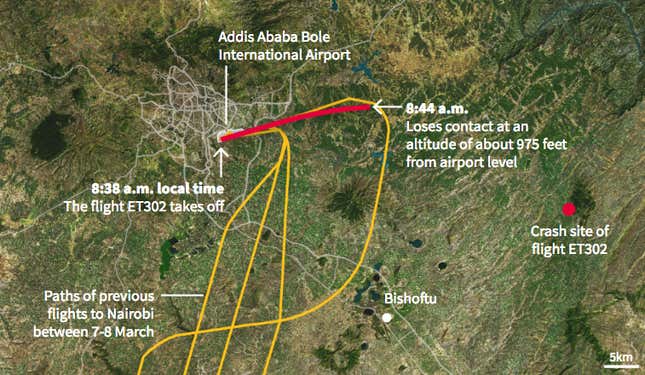

After its Nairobi-bound flight ET 302 took off from the capital Addis Ababa at 8.38am, the pilot reported problems and was cleared to return to Bole international airport. But the Boeing 737 Max 8 aircraft lost contact and plunged into a field in Bishoftu town minutes afterward, killing 157 people from three dozen nations. The crash was the deadliest in the state carrier’s history since it began operating in 1946.

For Africa’s largest airline, the crash has brought undue attention to its regional and global operations, its future aspirations, the impending plans to open itself up for private investment, as well as its decades-long relationship with the US aircraft manufacturer Boeing. The accident also posits a new and modern challenge for Ethiopian, which in its 70-year history has survived through political turbulence, a transition from a socialist to a market-based economic system, and intense global aviation competition impelled by technological advances and mergers.

“This is a setback and you cannot deny it, you cannot sugarcoat it,” argues aviation industry analyst Henry Harteveldt. Besides the “emotional impact” on the management and employees, what remains to be seen, he says, is how long this tragedy and the ongoing investigation into what actually happened could slow down Ethiopian Airlines’ (ET) short-term ambitions—whether by a year, two or even more.

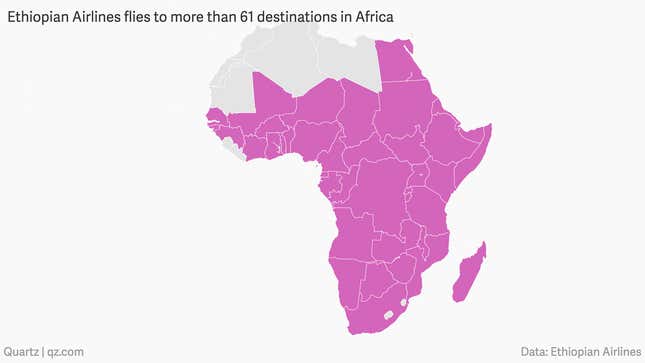

Over the past decades, Ethiopian has transformed from a domestic airline into a global carrier servicing 119 international destinations on five continents. With an operating fleet of 111, the company carries almost 11 million passengers annually and recorded $3.3 billion in revenues in the 2017/18 fiscal year.

It’s also implementing a strategic plan dubbed Vision 2025 aimed at positioning itself as Africa’s airline of choice. Its hub in Addis, which recently tripled in size, has already overtaken Dubai as the world’s gateway into Africa.

As more African nations move to liberalize air travel, Ethiopian has helped launch or revive their defunct sovereign airlines like Zambia’s or set up crucial transit and cargo hubs like in Togo and Malawi. To boost its technical and management services, last year Ethiopian announced it would set up a graduate business school to help young Africans gain organizational and industrial skills.

A huge part of the state-controlled enterprise’s ambition involves training pilots, cabin crew, and maintenance technicians at its aviation academy founded in 1956. Yet as impeccable and groundbreaking as the aviation school is, the crash is now raising questions over how regularly and extensively Ethiopian trains its pilots.

The ET 302 flight was captained by Yared Getachew, a 29-year-old with over 8,000 hours of flying, along with 25-year-old first officer Ahmednur Mohammed with 350 flying hours. But as investigations unfold, and similarities are drawn with the October Lion Air crash in Indonesia, a New York Times report questioned if any of the pilots were trained on the Boeing 737 Max 8 simulator, which the airline reportedly only just installed in January.

The system in question is the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS), a feature incorporated to direct the nose of the plane downwards if it is in danger of stalling. When the plane was first introduced, both Boeing and the US Federal Aviation Administration agreed pilots who had flown a related earlier 737 model didn’t need additional simulator training, nor instructions specifically about MCAS.

Ethiopian Airlines on Thursday (Mar. 21) said its pilots had completed the original training noting, “The B-737 Max full flight simulator is not designed to simulate the MCAS system problems.”

Boeing also announced it had developed a software patch and pilot training program to address issues with the Boeing 737 MAX. A US Senate committee is also set to hold a hearing with Boeing and other manufacturers on safety next week.

However, because the crashed occurred within an Ethiopian aircraft, Harteveldt says concerns will be raised on whether the pilots did everything they should have, and “what, if any, responsibility rests with Ethiopian and what responsibility would rest with Boeing.”

Era of privatization

As a flagship state company, Ethiopian Airlines is also one of the key government enterprises up for liberalization as part of wider reforms to revitalize the economy and reduce poverty. The airline holds a focal point in the Horn of Africa nation’s economy, promoting tourism, boosting the horticulture and floriculture industries through exports, and creating employment for tens of thousands of people.

Because it is state-backed, Ethiopian Airlines at this crucial juncture is “in a better position in terms of addressing the financial consequences” emitting from both the crash and the grounding of the 737 Max 8 passenger jets, says Chrystal Zhang, senior lecturer in aviation at the Swinburne University of Technology in Australia.

And even though crashes do have an impact on reputation, Zhang says the airline’s safety record, its rapid growth and high performance, their swift response to the crisis, along with Boeing’s faulty system designs means the crash won’t “damage the confidence of those investors who would be interested in this privatization initiative.”

To cushion itself, Ethiopian could “optimally redeploy its fleet to make up for the grounding of the 737 MAXs,” says Zemedeneh Negatu, an Ethiopian-American investor and aviation expert who acts as a transaction advisor to more than 15 airlines across Africa.

The airline’s 111-plane fleet is currently less than five years of age, with 63 more on order. As part of its global ambitions, Ethiopian hopes to increase its fleet to 200 and raise its revenue targets to $10 billion by 2025.

Assuring customers and partners

But beyond communicating with passengers and regulators and remaining forthright with the media, Zhang says Ethiopian Airlines should make assuring their employees a “priority.” Harteveldt agrees, saying there needs to be transparency with the staff on all levels around the recovery process and the timelines of the investigation.

“This is not something where they can initiate a price cut to get customers to come back or change delivery of airplanes,” Harteveldt said. “This is far more serious and far more substantial of a business challenge.”

Zemedeneh, who used to gaze at Ethiopian Airlines planes as a young boy in Addis Ababa, said the airline could also capitalize on the “confidence and loyalty” imparted by customers and aviation experts over its track record in the past week.

“This is a rare, unanimous respect given to [an] airline from an emerging market, especially in Africa.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox