Beijing wants to deploy international media outlets to allay fears about its trillion-dollar global trade and infrastructure initiative.

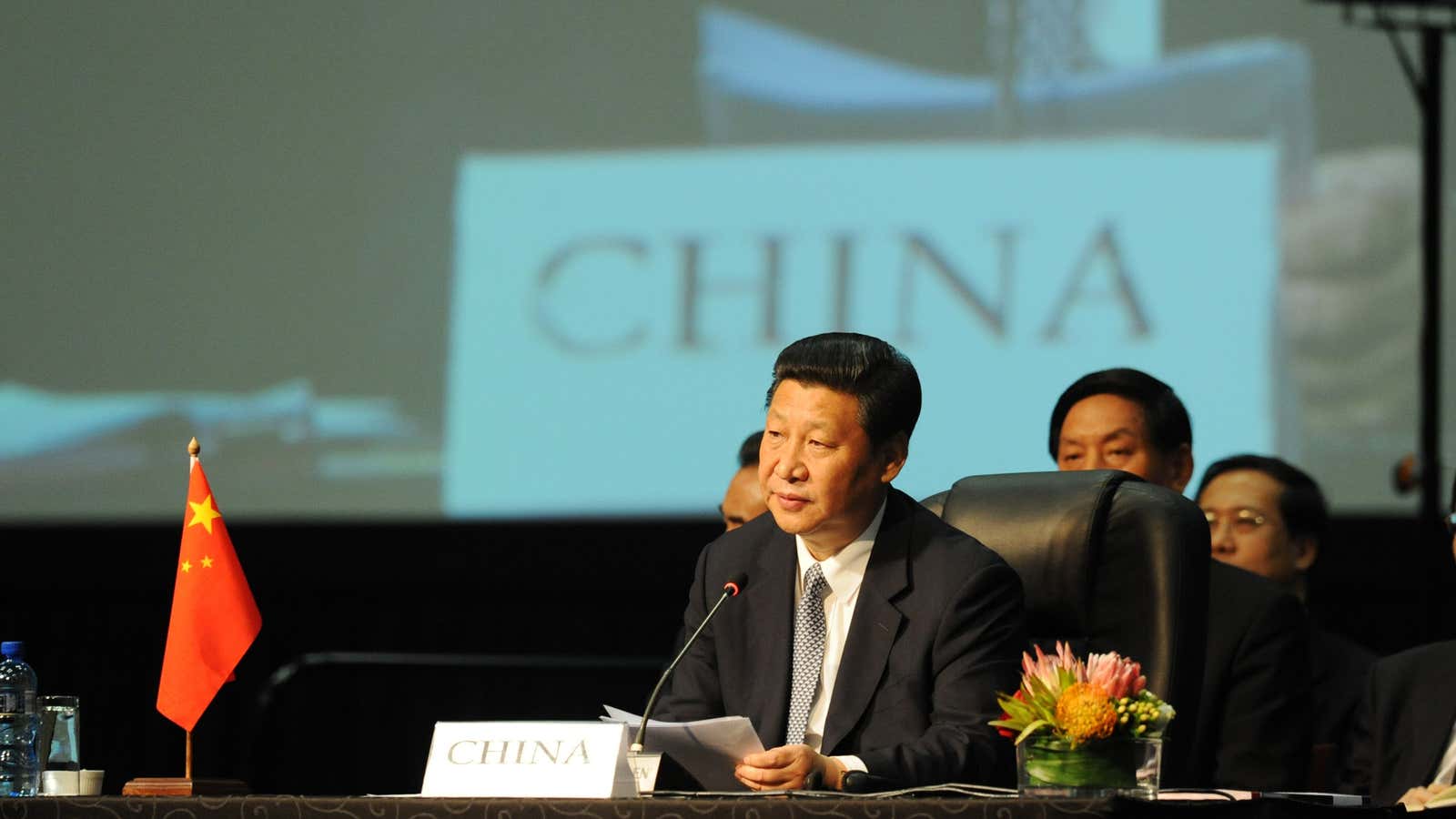

President Xi Jinping called on media outlets in the countries involved in the Belt and Road plan to fashion stories about the scheme in a way that boosts public support. Xi made the comments at the first council meeting of the Belt and Road News Network (BRNN), an association consisting of 182 media outlets from 86 countries which include China Daily newspaper, French daily La Provence, Russian news agency Tass and South Africa’s Independent Media.

The BRNN was first proposed by Xi in 2017 and is positioned as a platform to help nations along the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to cooperate in news gathering, improve technological support and enhance cultural exchanges.

Xi’s comments come as almost 40 world leaders gather in Beijing today to show their support for his signature foreign-policy plan. As the sweeping infrastructure project has taken hold, it has faced increasing criticism, particularly over its long-term viability in Africa.

There has also been a growing calls for caution on what has been termed “debt-trap diplomacy,” with African nations getting warned mostly by Western leaders on the perils of taking on too much cheap Chinese debt. Critics have also warned about Beijing’s debt relief or repayment processes, with many using Sri Lanka’s handover of its strategic Hambantota Port to Beijing last year as example of the risks associated with taking Beijing’s money.

The Belt Road Initiative has faced scrutiny in countries like Kenya and Ghana and has instigated legal challenges spanning three continents in Djibouti.

The move to solidify the BRI’s achievements through the media dovetails with Beijing’s efforts to expand its influence in Africa through “soft power.” This has mainly entailed financing Mandarin language courses besides movies that emphasize China’s role as a humanitarian actor and protector of world peace.

Since 2012, state-run media outlets have also pitched up in the continent, among them the Africa bureau of China Global Television Network (CGTN) and China Daily Africa newspaper. China also takes African journalists to Beijing for training, while state-linked firms have made investments in local media outlets including buying a 20% stake in South Africa’s Independent Media firm.

But that move has run into controversy in South Africa. Last August, when Independent columnist Azad Essa wrote a piece about the maltreatment of minority Uighur Muslims in China’s Xinjiang province, his column was removed, he alleged, in a bid not to displease the firm’s Chinese investors.

The Beijing-based StarTimes Group has also become one of Africa’s most important media companies, increasingly influential in the booming pay-TV market. As it spread its foothold in Africa, the company has embarked on a project to provide solar-powered satellite television sets to 10,000 villages across Africa.

On the digital front, Beijing is also exporting some of its restrictive online tools and measures to African governments—moves, activists note, pose an “existential threat” to the future of open internet spaces.

Xi’s bidding to use the media as a way to mold favorable public opinion also plays into how Beijing has long framed its partnership with Africa: mainly as an alliance of equals. As he said in his speech to the media association: The Belt & Road might have begun in China but its opportunities and outcomes belong to the world.

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox