Ethiopia’s tech startups are ready to run the world, but the internet keeps getting blocked

Getnet Assefa shuffled uneasily in his office seat and wondered aloud why he couldn’t connect to the internet on his laptop.

Getnet Assefa shuffled uneasily in his office seat and wondered aloud why he couldn’t connect to the internet on his laptop.

It was mid-morning on Tuesday (June 11), and even though he didn’t know it yet, it was the beginning of the latest days-long internet cutoff. Authorities in Ethiopia disrupted connectivity nationwide to prevent students from cheating in national exams. Social media platforms like WhatsApp and Telegram were restricted, SMS text messaging disabled—leaving banks, businesses and tech startups in a quandary.

For Getnet, the founder and chief executive of Ethiopia’s first artificial intelligence lab iCog, an internet shutdown meant not just hours of wasted productivity. It was also about losing “trust” from clients—spread across Canada, Hong Kong, Japan, and the United States—with whom they are working on projects ranging from machine learning to computational linguistics and robotics. iCog is where Sophia, the humanoid robot that was granted Saudi citizenship in 2017, was partly developed.

As a heavily regulated market with low internet penetration, young techies in the Horn of Africa nation, he says, already suffer from the negative perception that they couldn’t be where Africa’s next high-tech workforce is nurtured. Instead of boosting tech spaces, the government shouldn’t worsen conditions with these internet blackouts, Getnet complains. It supports the impression the ecosystem is “a place that’s surviving by donation, by funding, not by doing.”

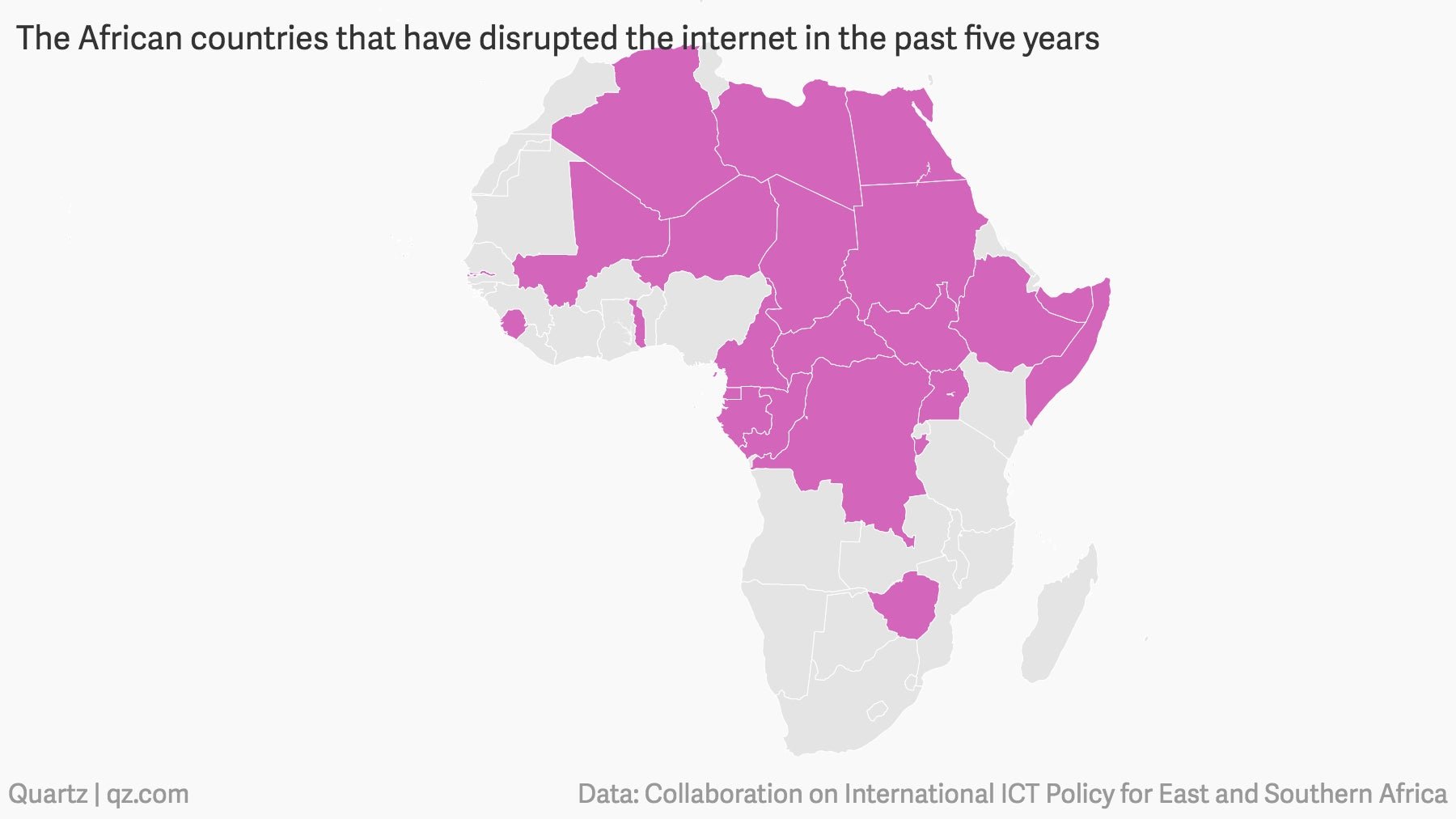

When it comes to internet disruptions in Africa, Ethiopia isn’t an anomaly. At least 22 African states have partially or fully blocked the internet or obstructed social media networks in the past five years due to a political uprising (Algeria, Sudan); before, during or after elections (DR Congo, Benin); and ahead of national examinations (Algeria, Somalia).

Across the African continent, internet stoppages are getting longer, more sophisticated, and targeted, with dictators being the most frequent culprits.

“State-ordered internet shutdowns are on the verge of becoming the ‘new normal’,” says Dawit Bekele, the Africa regional director for the Internet Society. Governments or telcos like the state-run Ethio Telecom also seldom provide information or decline to comment on why they undertook such measures.

Yet for all the variety of stated reasons, “the underlying goals served remain constant: public opinion is shaped, critics of state and leaders are suppressed, and power is consolidated,” says Alp Toker, director of internet monitoring organization NetBlocks. “Regardless of context, we have found that democracy is always weakened and the rights of individuals are always violated.”

Those contraventions can have a dire consequence for Ethiopia’s fast-emerging tech scene, also known as ‘Sheba Valley.’ Under its reformist prime minister Abiy Ahmed, the 100-million nation has been drafting laws to privatize some state-owned entities including in the telecoms sector where it announced on Tuesday it is opening up to foreign investors.

Officials also say they want to harness the potential of innovation in science and technology to create jobs and drive the country’s overall development ambitions. Data tariffs have also been reduced, hundreds of websites unblocked, and bloggers and journalists released en masse.

Yet official rhetoric hasn’t matched action sometimes: the government blocked the internet in the eastern Somali region last year to quell protests. The latest shutdown also happened just days after the ICT Expo and the Startup Ethiopia events, where authorities promised to boost both the startup community and internet landscape.

“It really limits your potential,” says Frewoini Gebrewahid, a senior quality assurance analyst with EQOS Global, a firm that that provides outsourced tech services. Despite longing to make Ethiopia the next business outsourcing destination, Frewoini said they wouldn’t offer cloud services or set up a call center now for fear they might disappoint clients during a shutdown.

Adam Abate runs Apposit, an Addis Ababa-based software development company that is a technical partner to Nigeria’s leading mobile payment systems Paga. During net cutoffs in the past, Adam says they have “had to fly to Kenya,” approximately a two-hour flight away, just to access connectivity.

“It’s frustrating,” he notes. “Luckily it doesn’t happen too often but even the fact that it happens potentially once a year is too much.”

Ethiopia has shut down the internet at least twice every year since 2015 whether during anti-government protests, state of emergency, or to limit exam cheating. For every day the internet is blocked, NetBlocks estimates Ethiopia loses over $4.4 million.

Internet blackouts remind Nati Gossaye about the time when his own firm Langbot, which uses AI and gamification to improve language fluency, never took off. While competing in Facebook’s Bots for Messenger challenge in 2017, Nati found himself unable to make his final submission after authorities interrupted connectivity to prevent exam leaks.

Trying to figure out what to do, he called a friend working at the African Union headquarters to see if they had connectivity. Sometimes hotels, embassies, and United Nations offices have access. After finding out they did, Nati went there, submitted his application, and days later, found they had won the $20,000 they later used to launch their platform’s Beta version.

“We almost didn’t get that,” he remembers. “I don’t know why the authorities can’t find solutions that are less catastrophic.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox