The Ethiopian Airlines 737 Max crash could warrant historic punitive damages against Boeing

George Kabau’s family remembers him as a dedicated professional with unflappable geniality, innate warmth, and remarkable resourcefulness.

George Kabau’s family remembers him as a dedicated professional with unflappable geniality, innate warmth, and remarkable resourcefulness.

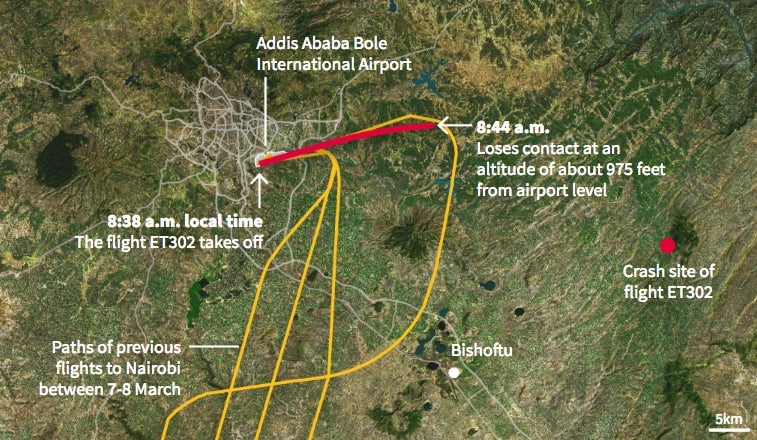

The 29-year-old was an engineer with General Electric in Kenya and was among 157 people who died on the crashed Ethiopian Airlines flight in early March. Four months after the plane plunged into a field in Bishoftu town minutes after take-off from Bole international airport, the family says they are yet to reconcile with how their loved one perished. One of five siblings—three lawyers and a banker—George was a source of pride amongst them and had a bright future ahead of him.

In April, the Kabaus became the first Kenyan family to sue Boeing in the US, seeking to hold the manufacturer liable for the crash. The Ethiopian crash, along with the Lion Air plane that fell in Indonesia last October, were both linked to bad sensor data triggering an automated anti-stall system in the Boeing 737 Max model which directs the plane sharply downward.

Through their lawyers, the family said they wanted to force the company to release documents related to the troubled 737 Max 8 model, admit that it prioritized profits over safety, failed to properly inform pilots about the dangers and risks associated with the MCAS, and call on juries to impose punitive damages.

“This was a deliberate death caused by recklessness,” says Tom Kabau, George’s brother and a lawyer based in Nairobi.

The case is indicative of the legal showdown about to commence between families and the world’s biggest commercial aircraft manufacturer. The lawsuits lodged over the Ethiopian Airlines crash also posit a challenge for attorneys, who will have to decide with families whether to face-off with Boeing publicly and seek damages exceeding simple compensation or reach out of court settlements.

There’s also the question of time, and if the proceedings could protract beyond the two-year threshold attorneys expect—especially if Boeing puts a strong defensive strategy against much-publicized cases like Kabau’s. There’s also the quandary about how the facts of the cases filed in the early weeks have changed and might need to be amended, especially as new details emerge about the 737 Max’s flaws.

For families of the deceased, this might mean “further court processes, significant delays, and greater expenses,” says Joseph Wheeler, the founder and legal practice director of the Brisbane firm International Aerospace Law & Policy Group (IALPG) in Australia.

In late June, Wheeler’s firm filed a class action lawsuit against Boeing on behalf of over 400 pilots from a major international airline they are currently keeping anonymous. The case will be heard in October, he said. American families including those of consumer activist Ralph Nader’s great niece, have sued Boeing, along with a Rwandan family. Shareholders have also sued Boeing accusing it of concealing safety deficiencies in its 737 MAX planes.

Given the popularity of the Addis Ababa-Nairobi route, and the number of prominent professionals who died on ET 302, many more families are expected to take legal action against the Chicago-headquartered manufacturer too. Passengers from 35 countries were on board the Ethiopian flight. Kenya suffered the largest number of casualties, with the deceased 32 people including university professors, an ex-sports administrator, hotelier, and business directors.

Seeking punitive damages

If Boeing fails to get the complaints out of US territory, as it has succeeded in the past, juries might consider awarding punitive damages. Courts usually grant these hefty damages as a way to tell defendants their conduct was so egregious as to shock the conscience.

Yet punitive damages are often unavailable or limited when it comes to aviation lawsuits, says founder of the Chicago-based aviation law firm PMJ, Patrick Jones. But if plaintiffs can show there was willful or wanton misconduct or reckless disregard for passenger safety, that could warrant compensation. In this scenario, Jones says that could run into hundreds of millions of dollars on top of the basic claims.

“I think Boeing is going to be more entrenched in this case than they ever have been [or] that any defendant has been,” he says.

For Boeing, the severity of the 737 Max grounding, the canceled orders, dropped shares, reputational loss, besides the demands for compensation from airlines over lost revenue only “gives them more fire to defend,” says Kenneth Rukunga, a compensation lawyer in Perth, Australia.

Rukunga, a Kenyan, has already been to Nairobi along with Wheeler seeking to work with families whose members died in the Ethiopian crash. While some cases might be resolved quietly, he says, the planemaker will defend against the public litigations and even appeal if they get a decision commanding them to pay punitive damages.

Honoring George

As they wait for their day in court, George Kabau’s family is establishing a foundation in his name to help youngsters study engineering and science. Through their case, they also hope to push Boeing to change how it operates and be accountable for its actions.

“Our concern here is that business will not override human rights,” Tom Kabau says. “This justice is not only for George but all of us.”