The miscalculations African governments keep making with social media and internet blocks

A few minutes after 11pm on the night of June 22, Ethiopia went offline.

A few minutes after 11pm on the night of June 22, Ethiopia went offline.

The move wasn’t unprecedented in the Horn of Africa nation: With a single, state-controlled internet provider, authorities have for years disrupted connectivity during anti-government protests, state of emergencies, and national exams. Officials resorted to this old gambit amid reports of a coup attempt targeting the northwestern Amhara regional state. Following a year of hopeful political, economic, and diplomatic progress, the bloody putsch threatened to derail the democratic transition of Africa’s second-most-populous nation.

The shutdown in late June inconvenienced users and businesses, stoked dissatisfaction with prime minister Abiy Ahmed’s reformist administration, and disrupted the ability of journalists to verify information. But it also reanimated questions academics and activists have increasingly asked in the past few years: why do governments restrict internet access? Are they justified in doing so? And do these measures work?

The first known digital blackout in sub-Saharan Africa happened in 2007 when Guinea’s former president Lansana Conté ordered a shutdown following protests calling for his resignation. Since then, perhaps encouraged by the rise of social media, an estimated 26 out of Africa’s 54 states have overseen a network disruption, with the 2011 Arab Spring protests especially popularizing them as a response tactic during social unrest or mass anti-government rallies. The cutoffs have been complete or partial and have varied in geographical range and platforms affected.

Activists say the cutoffs—along with more recent punitive online and social media regulations—coalesce to extinguish access to the internet and constitute a threat to fostering open, pluralist, and democratic societies. In a continent with divergent political realities and internet penetration levels, many point to the irrefutable role of digital communications to protest authorities and improve lives.

Yet others touch on the internet’s role in fueling violence, making the case for social media as the modern equivalent of the role played by radio in 1994 Rwanda or text messaging in 2007 Kenya in spreading rumors, instilling fear, and mobilizing perpetrators to violence. Cognizant of this history, and given their inability to control what people share online, governments across Africa have repeatedly used the argument of preserving order as a reason to curtail internet access.

In Uganda’s 2016 polls, the communications regulator ordered operators to cut connectivity in an election dogged by violent protests and arrests of opposition candidates. In early 2018, Chad’s president Idriss Deby blocked social media for over a year for “security reasons” even though less than 7% of the 15 million population have internet access.

Following a crucial presidential poll, authorities in DR Congo enforced internet restrictions to prevent the circulation of fake results online, and to avert “chaos” and a “popular uprising.” During civilian protests in January, Zimbabwe ordered an internet blackout even as authorities rounded up opposition leaders blamed for the unrest. During the 2017 elections, Kenyan officials also threatened to cut connectivity if things “get out of hand.”

Ethiopia is one country where observers have said hate and dangerous speech online has triggered or exacerbated violence that has displaced 3 million people in recent years. Despite low internet usage among its over 100 million people, the government has found it difficult to parse and stop the disinformation “through conventional means,” says Felix Horne, ex-senior Ethiopia and Eritrea researcher at Human Rights Watch.

In response, Ethiopian officials have promised to introduce a law on hate speech with premier Abiy promising to switch off the internet for as long as possible whenever they deem necessary. “Internet is not water, internet is not air,” he said back in August.

Ineffective tool

Observers, however, note that shutdowns are a blunt tool when compared to how quickly rumors and disinformation travel offline, particularly in low-connected countries. The same applies to highly-connected societies, where elites can leverage their social, digital, and political capital to organize and expose abuse, and in the case of a blackout, mobilize offline.

“We must remember that shutdowns are not a surgical, targeted ‘foot-in-the-door’ technique to root out dangerous language—they are the digital equivalent of breaking down the door,” says Jan Rydzak, who studies shutdown dynamics at Stanford University’s Global Digital Policy Incubator.

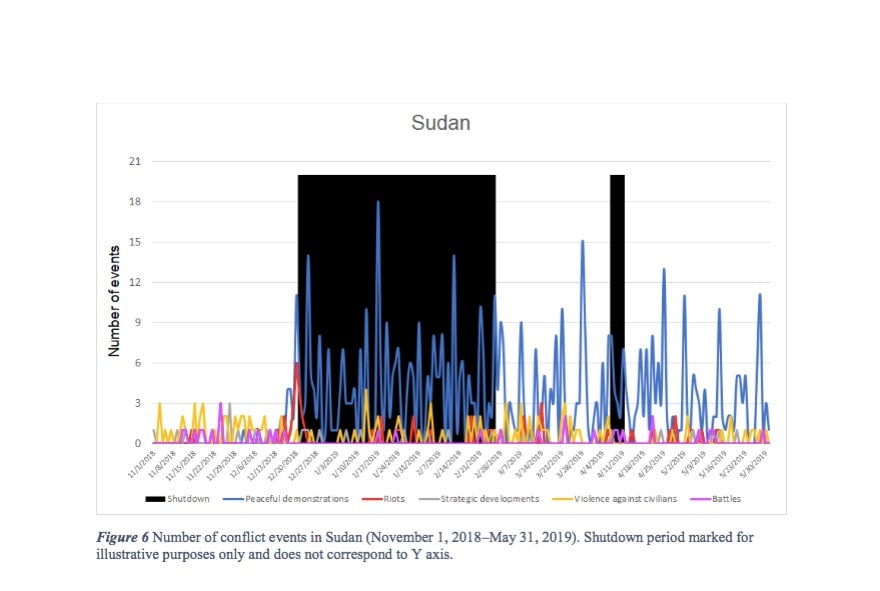

Researchers have pointed out how both protestors in Egypt and violent insurgent groups in Nigeria adapted to the information vacuum that comes with a shutdown by falling back on more traditional strategies. In Sudan, new unpublished research shows social media restrictions didn’t hinder peaceful protests, with some of the largest spurts in individual demonstrations happening during cutoffs in December and January. In Algeria, the calls for former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika to vacate office intensified even as his administration blocked the internet in a piecemeal fashion.

“There is very little evidence that turning off access is effective at all,” says Rydzak. Blackouts sow instability and uncertainty, he says, and as they become normalized, might open the door for its regular application in more contrived situations. “Their repercussions echo beyond the borders of a single country.”

Learning from each other

Indeed, more African governments are drawing from each other’s repertoire of control tactics by imposing blackouts. Federal and regional states, post and telecommunications authorities, and security agencies have all carried out shutdowns. Recent research also shows the less democratic an African state, the higher the likelihood it will order internet disruptions. Yet governments do not expect to be held to account, with some like Gabonese president Ali Bongo blaming jammed cell networks during a month-long digital curfew in 2016.

Put together, blackouts can have “far-reaching consequences,” says Juliet Nanfuka of the research center, the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa. These include getting locked out of basic rights and services including health, education, and economic opportunities.

Rydzak says shutdowns can also have an “overall chilling effect” on free expression and feed into the darker narratives surrounding social media platforms. “Blackouts can change people’s perception of the internet or a social media platform and impart the idea that they are unsafe to use,” he says, hence discouraging adoption of technology in low-connected environments.

Increasingly, state actors are using so called fake news and the risks of viral disinformation as their stated reasons for blocking the internet during disasters, terrorist attacks, and social unrest. But governments could do better by working with civil society and media outlets “to help surface, expose, bust, and counter disinformation,” says Julie Posetti, who leads the Journalism Innovation Project at the University of Oxford.

Regulators could also work with social media platforms directly: Facebook, for instance, will employ approximately 100 people by end of 2019 to review flagged content in languages including Somali, Oromo, Swahili, and Hausa, says the firm’s head of public policy in Africa, Kojo Boakye.

Authorities and telcos could also clarify the limits and timelines of shutdowns instead of apologizing later on as Ethio Telecom and Orange Liberia did this year.

But as the use of cutoffs spread across Africa, many more users will resort to virtual private networks to circumvent censorship says Berhan Taye, who leads a global campaign to stop internet shutdowns at Access Now. Legal challenges against government-ordered shutdowns have been increasing too, with cases, some successful, filed in nations including Uganda, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Cameroon, and DR Congo.

Ultimately, Berhan says, “the nuclear option of shutting down the internet is not going to be sustainable.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox