On the first day of class, as a way of introduction, I asked the 15 diverse students in my class at the School of Visual Arts in New York City why they chose to take Afrodiasporic literature.

One after another, these young men and women from America, India, Haiti and China stated what motivated them to register for the course. Most of them felt it would be a good addition to their knowledge of the world. Only three of them had been to Africa. One went to Egypt, one to South Africa and the other visited her parents’ country of Nigeria.

Of all the students, only two knew Chinua Achebe and had read Things Fall Apart. One had read Chimamanda Adichie’s Americanah. One student told me that he honestly picked the Afrodiasporic literature because it worked with his schedule and he needed a three credit elective to complete his required credits in order to graduate.

When I created the course, I sold it to the college as a bridge that would introduce American students to African literature by first introducing them to the lives and world of Africans in their midst. Instead of dumping them in the world of Achebe’s Umuofia before the Europeans came, we lure them to Africa in a gradual way. We follow the lives of Africans in America as they go to Walmart, eat at familiar places like Burger King before they immersed themselves in a feast of ugali and nyama choma at a marriage ceremony in Boston where a young man from Nigeria paid dowry for a wife from Kenya.

The course promised to give students a unique opportunity to expand their horizon and see America from the perspective of outsiders with different viewpoints. Despite their sense of alienation, Afrodisaporic writers’ distinct reinterpretation of Africa for the world provides contexts that make it easy for the uninitiated to absorb African narratives that are neither sanitized nor westernized.

This cross cultural exchange has become more important because the recent US population census showed that since the 1990s, more Africans have voluntarily migrated to North America than all the Africans that were forcefully brought to America in 400 years of transatlantic slave trade. Some of these Africans came as migrants taking advantage of a broadened US immigration policy of the 1980s, some as students seeking knowledge and some others as refugees from some of Africa’s strife hotspots. Irrespective of how they came, they seem to have embraced the American ideals and utilized the opportunities that America provides.

According to Migration Policy Institute, a Washington DC-based think tank’s 2017 report on sub-Saharan African immigrants in the US, out of the 1.4 million African immigrants who are 25 and older, 41% have a bachelor’s degree, compared with 30% of all immigrants and 32% of the US-born population. The New American Economy study of the same population in 2017 noted up to 16% had a master’s degree, medical degree, law degree or a doctorate, compared with 11% of the US-born population.

While these Africans have not established significant political relevance in America, they have contributed to the society as a whole. The New American Economy says African immigrants contribute more than $10.1 billion in federal taxes, $4.7 billion in state and local taxes, and $40.3 billion in spending power. In their ranks are more than 32,500 nursing, psychiatric or home health aides, more than 46,000 registered nurses and more than 15,700 doctors and surgeons.

Within this diverse population, conversations are ongoing about their new society where they have called home and the world they left behind. These stories are being told and documented by African writers in the US. The works have become significant and are often referred to as Afrodiasporic literature in America. It is a genre that Western publishers have come to embrace.

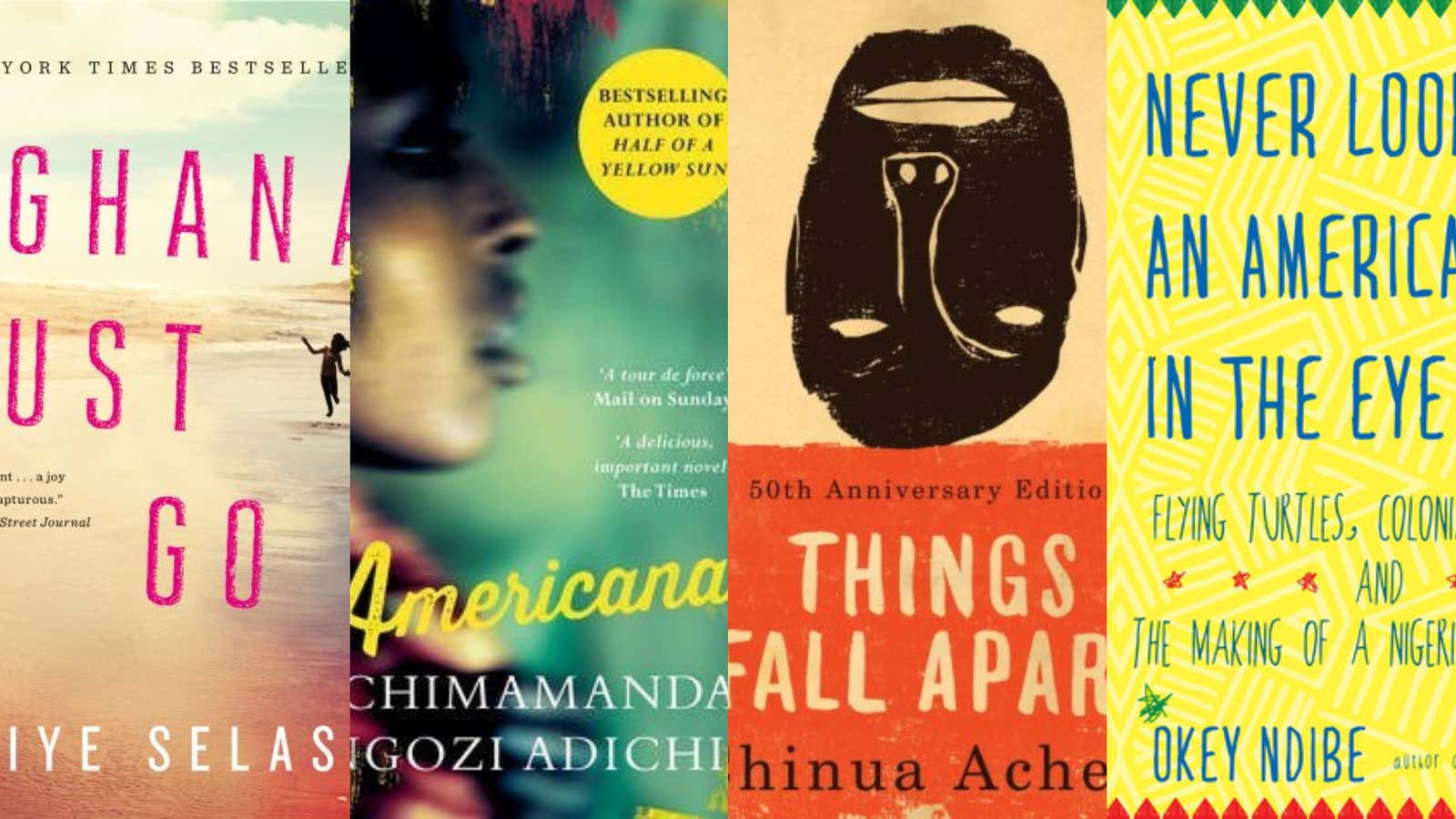

Some of the texts we used in the course include, Binyavanga Wainaina, How to write about Africa, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Americanah, Taiye Selasi, “Ghana Must Go,” Okey Ndibe, Never Look an American in the Eye,” and by myself: This American Life Sef. Our texts are also supported by visuals like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Ted Talk, “The danger of a single story,” Rahman Oladigholu’s movie, In America: The Story of the Soul Sisters, Lonze Nzekwe’s Anchor Baby and documentaries like Pippa Scott’s King Leopold’s Ghost and Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s Africa’s Great Civilizations.

My first assignment to the class after studying Binyavanga’s How to write about Africa, was to imagine that they were sent to an African country by The New York Times to cover the most important story of the day in that country. Out of the 54 countries in Africa, each student chose an African country to visit and also the most important story to cover during that visit. What they brought back a week after was a mixture of travelogue and journalism piece that paid great attention to the pitfalls sarcastically elaborated in How to write about Africa.

Since African writers started coming to America to study and hone their craft, they have been making their observations of America known in works of fiction, non-fiction and, most recently, memoirs. While the Achebe’s, the Soyinka’s and the Ngugi’s shared African stories with the world, most modern contemporary African writers abroad are sharing stories of Africans living in whatever part of the world they live.

Adichie’s Americanah chronicles the journey of Ifemelu to America, her observations of the American society, how it changed her and contributed to her decision to return to Nigeria. In the same breath, it showcases the journey of Ifemelu’s boyfriend, Obinze, to the United Kingdom and his experience with people who once colonized Nigeria.

In Never Look an American in the Eye, Okey Ndibe accomplishes the same feat of telling the story of his journey to America and his observations of America using the memoir format. Taiye Selasi’s Ghana Must Go sheds light on how the so called Afropolitians who supposedly had it all, at home in the West and also in Africa, battle with the dysfunction that displacement and alienation bring about.

Sarah Ladipo Manyika accomplished the same feat of telling a moving Afrodiasporic story in Like A Mule Bringing Ice Cream To The Sun, a story about San Francisco based Nigerian woman dealing with aging and longing and celebrating the past while accepting the present.

Exciting new talents like Akweke Emezi in Freshwater, brought her character, Ada, with all her ogbanje friends, to America. She let her traverse America without any care or any fear, wrecking lives and adding to a complicated image of an African in the lives of people she met. Chigozie Obioma, called a “heir to Chinua Achebe” by the New York Times for his first novel, The Fishermen, situates the story in Nigeria during the 1993 election. But in his 2019 Man Booker Prize shortlisted book, An Orchestra of Minorities, he takes his character to Cyprus where Obioma got his first degree. In An Orchestra of Minorities, Obioma pulled off what no African writer has ever tried. He chose to have his character’s chi as the narrator of the story and still left Western readers in awe.

African writers in the diaspora are taking the conversation to the communities where they live. Before now, Africans were the ones bending over to read the works of Western writers. Now, with bestselling African writers like Chimamanda Adichie, Helen Oyeyemi, Chigozie Obioma, Tomi Adeyemi, Nnedi Okorafor, etc, the much-touted conversation between Africa and America has started in earnest.

One of the highlights of my year was Ndibe’s visit to the class while we were studying his memoir, Never Look an American in the Eye. The students were so excited to meet an African writer and had tons of questions for him.

I want to believe that as a result of taking this course, the imaginative space of my students was expanded in a way that they experienced what Ben Okri calls “strange corners of what it means to be human.” At the end of the class, I started to read the first draft of Okey Ndibe’s latest novel, Valley of Confessions. From what I have read, I have no doubt that African writers are not stopping at bringing the African experience up for the world to see. They are venturing into a new arena where they bring the world to Africa to experience the continent first hand.

Anyone can accuse the African writer of any number of failings but not that of abdicating the task of telling their stories. Achebe would be proud to know that the African writer has heeded his call that, “until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

Sign up to the Quartz Africa Weekly Brief here for news and analysis on African business, tech and innovation in your inbox