Running on empty

Hello Quartz readers,

Hello Quartz readers,

At 7:52pm on April 17, Vinay Srivastava, a 65-year-old journalist in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, tweeted that he was unable to access any doctor or hospital over the phone, even as his SpO2 oxygen levels dropped to 52. At 3:17pm the next day, Srivastava tweeted a photo of his oximeter showing a level of 31. An hour after that, his son replied to that tweet, sharing that Srivastava had died.

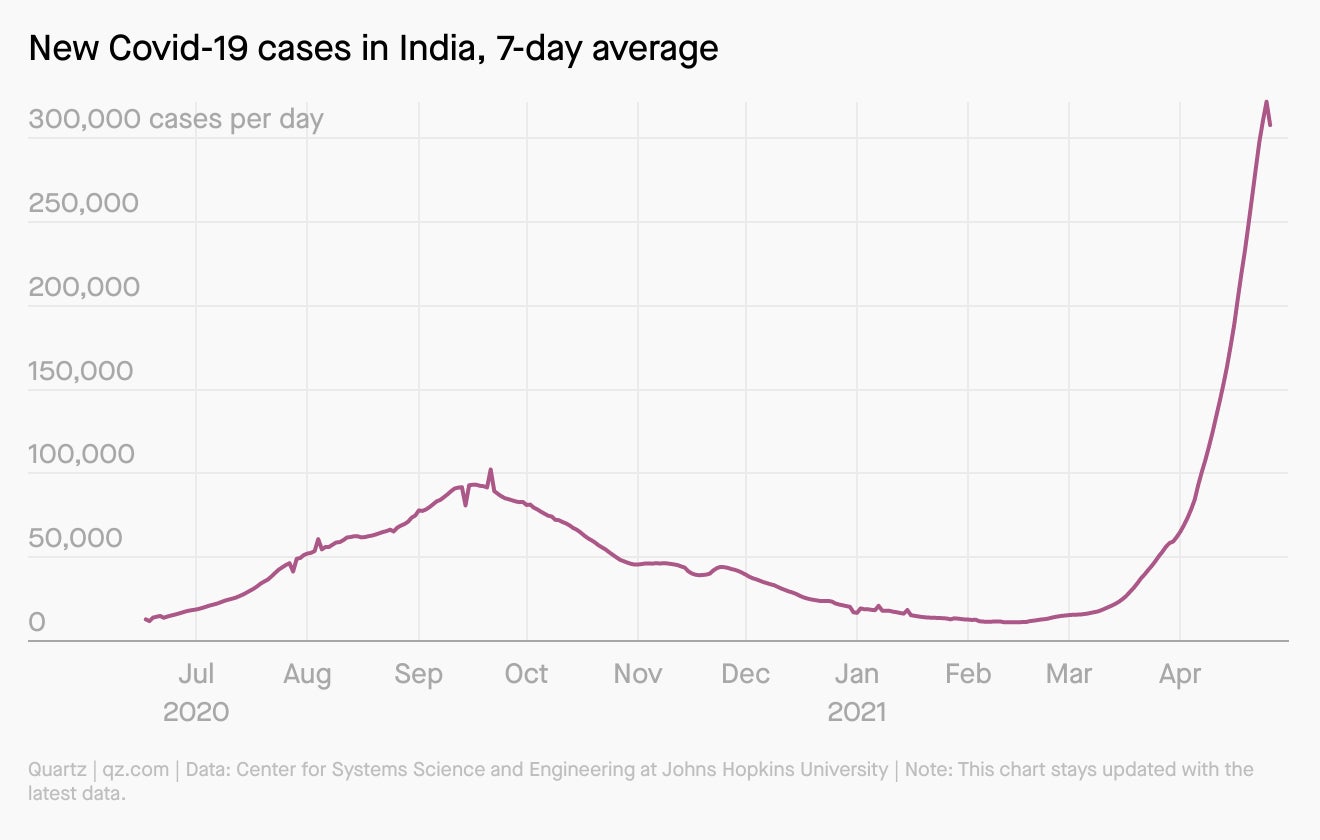

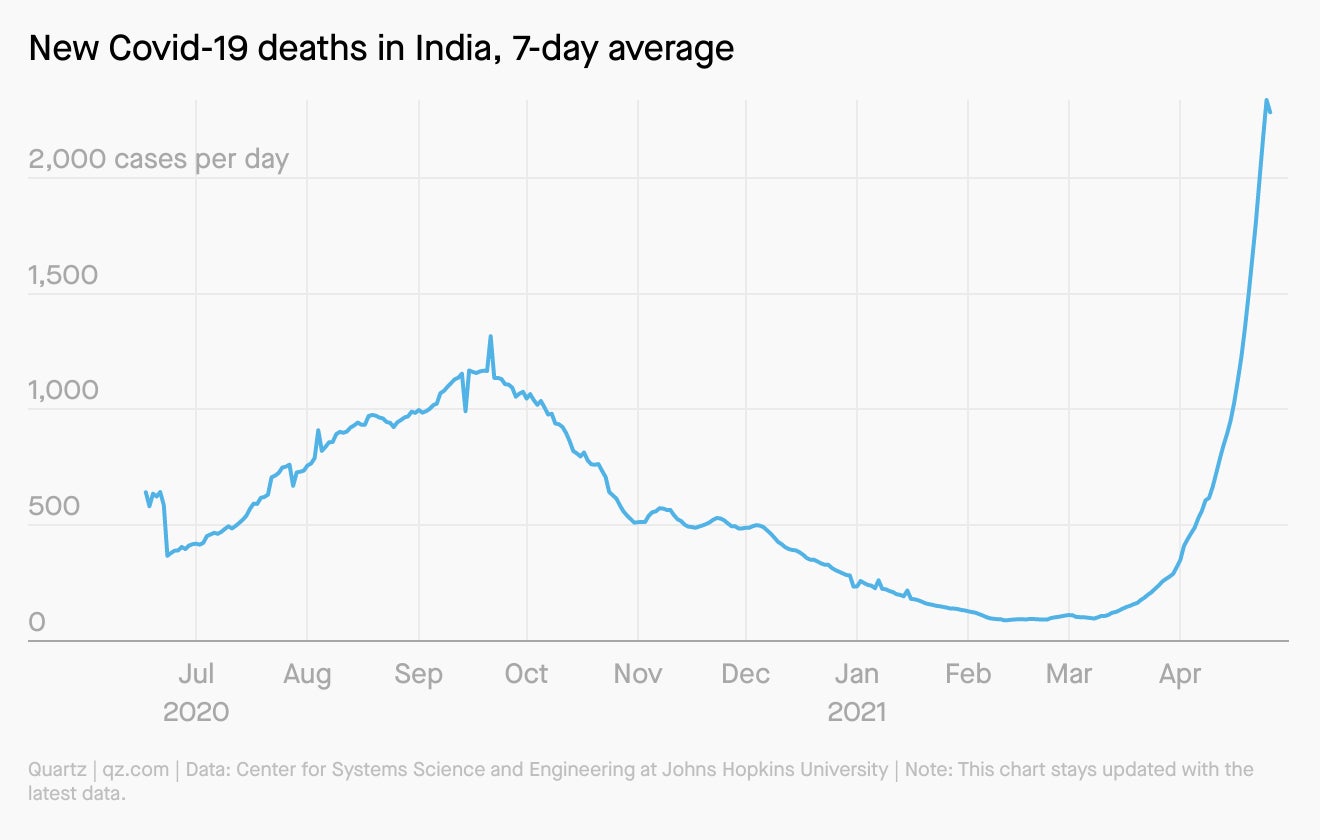

Ten days later, this is just one of the many deaths that Indians have collectively witnessed. On April 26, the country clocked 323,144 new Covid-19 cases, its sixth consecutive day of more than 300,000. The severe second wave has brought India’s healthcare system to its knees, leading to pitched battles and desperate pleas for plasma donors, treatments like remdesivir and doxycycline, hospital beds, and oxygen cylinders. Some of the biggest hospitals have been forced to go to court over their oxygen supply; on April 24, around 20 patients died at one Delhi hospital that ran out of oxygen entirely.

The visuals are nothing less than apocalyptic: Rows of dead bodies wrapped in white cloth, mass cremations, pyres burning on footpaths due to lack of space, desperate patients and families waiting at hospital gates for days. To be sick is to live in mortal fear of anything beyond a mild case and a swift recovery; to be healthy is to hole up indoors for a 13th consecutive month, contending with fear, anxiety, sadness, anger, and disbelief—not knowing if your friends and family will survive the year, or when you might see them again.

The government is complicit in this breakdown. Deaths are soaring, yet local elections continue without interruption, and many in India continue to flout safety measures. State governments are passing blame to the top, while fudging their own data. And the central government’s response can be summed up in one anecdote: On April 17, while Srivastava was tweeting his imminent death, prime minister Narendra Modi hosted a massive rally in West Bengal. Maskless, Modi told the crowd he was “elated” to see so many people gathered together. —Itika Sharma Punit

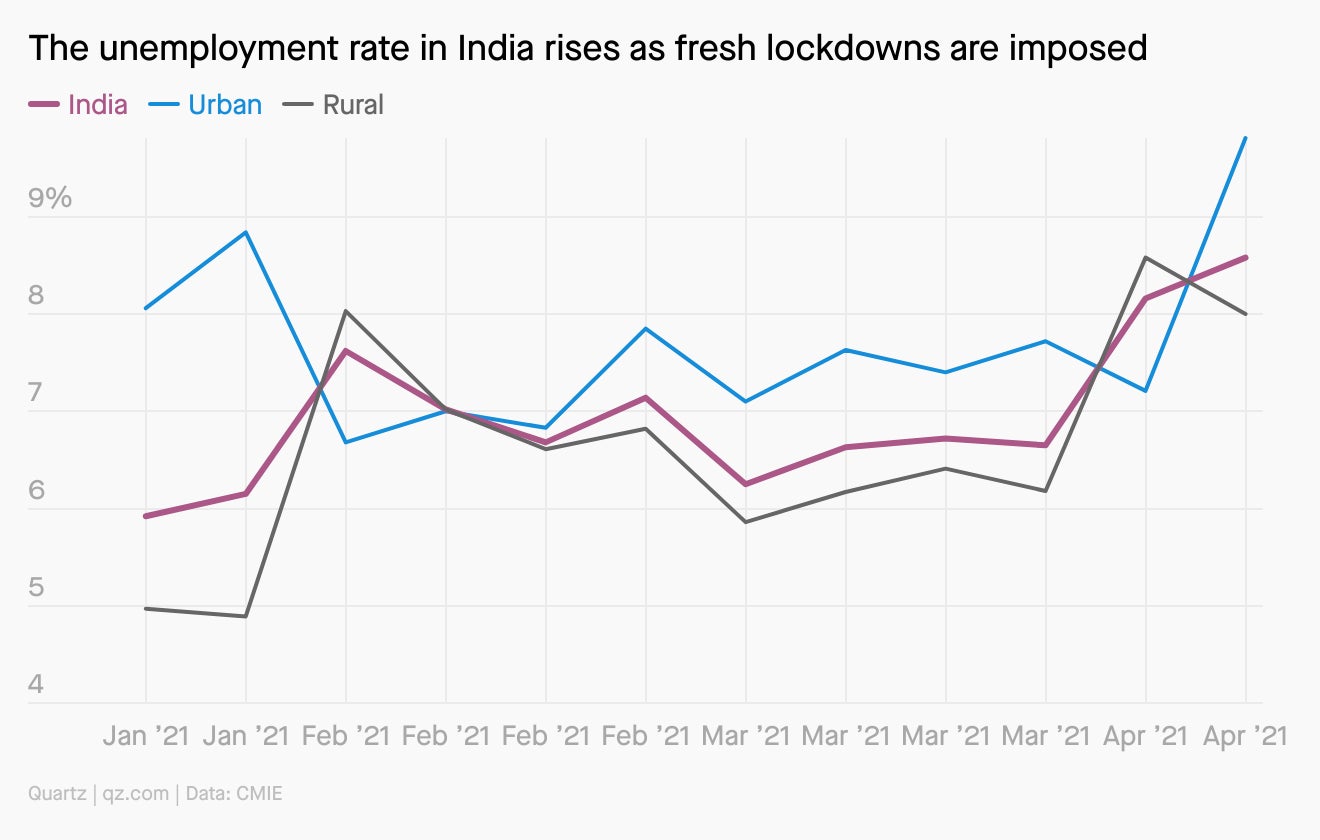

India’s crisis in charts

Keep tabs on the virus’s economic impact with our coronavirus living briefing, and follow Quartz India for more of what you need to know. Here’s the latest:

- Many countries are helping India contend with the crisis.

- And many in India are disappointed with the tepid US response.

- Indian companies are stepping up to fight the oxygen shortage.

- While Indian hospitals put out SOS calls on social media.

- (Here’s why it’s so hard to get oxygen cylinders in the first place.)

- India’s grassroots lockdown isn’t helping enough.

- School teachers are manning a Covid-19 war room.

- Yet local elections are continuing in some areas.

- The economy is already being impacted.

- Bad loans are hitting the banking system.

- All while India has been exporting millions of vaccine doses.

- And the huge Indian diaspora struggles to help.

Three dinner-table convos

⚕️ Covid-19 showed the US how universal healthcare could work. As of 2019, roughly two-thirds of Americans with healthcare got it through a private company. But during the pandemic, the US provided access to Covid-19 tests and vaccines for free, while heavily subsidizing hospital visits for the uninsured. It’s essentially a scaled-down version of universal healthcare, and a potential test case for how the federal government could expand coverage.

💉 Biden’s vaccine aid pledges are meaningless. The US keeps touting its multibillion-dollar commitment to Covax, a WHO-backed multilateral drive to pay for vaccines for developing countries. But the way the vaccine procurement process is set up, these donations don’t mean much. There still aren’t enough vaccines for poorer countries to buy—wealthy countries are hoarding them—and a proposal to temporarily waive intellectual property protections on vaccines was blocked by the US, UK, and European Union.

🔎 Millions of workers are planning to switch jobs. More than 40% percent of respondents to a recent global survey said they are considering leaving their employer this year. Another survey, of North American workers, found that 52% expect to look for a new position in 2021. The pandemic has led to a “very real experience that employees have had around a lack of career progression, and a concern around skills development,” Rob Falzon at Prudential tells Quartz. People feel “that they’ve been working very hard, but they’re not really seeing opportunities to progress.”

✦ To learn more about what a year of Covid has done to work, check out our field guide on the subject, available to Quartz members. (Snag a free trial here.) While you’re at it, sign up to receive The Memo, our weekly newsletter on the modern workplace.

You asked

Why is the effectiveness of current vaccines so short-term (six months to one year) compared to other vaccines that are for life?

For now, we only have data for current vaccines’ efficacy at six months because that’s how long they’ve been around. The earliest data comes from the earliest clinical trials testing these vaccines, which occurred a little under a year ago.

Longer term, “there are two things that are primarily responsible for the durability of vaccine protection,” says Kevin Bonham, a senior research scientist at Wellesley College. “One is the vaccine itself and the other is the pathogen.”

Vaccines that provide the most protection, like the one for measles, work so well in part because the measles virus doesn’t mutate much. Vaccines like the annual flu shot provide less protection because the virus mutates year after year. Manufacturers rely on educated estimates as to how it will mutate, and then quickly design and make vaccines that confer protection.

Typically, coronaviruses don’t mutate often, but this pandemic has gone on long enough that the virus evolved new strains—the big question is whether existing vaccines will protect against them. So far, it seems like at least some of the vaccines available will, but scientists are still collecting data.

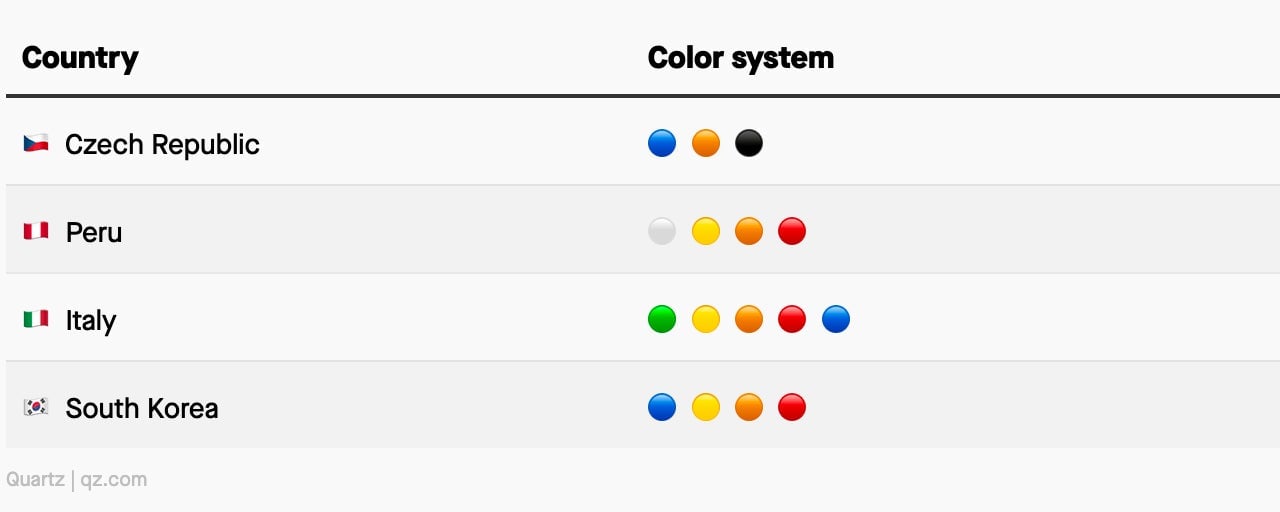

Panic palette

Can you match the country to its Covid-19 colors?

As case levels fluctuate globally, many health officials are using color systems to alert constituents about the virus’s threat level. But not everyone took the traditional 🚥 route. Amanda Shendruk and Anne Quito examined 35 warning-status color palettes used around the world; while red seems to be the universal sign for “very bad,” there is otherwise a lot of variance.

(Answer 🔑, top to bottom: Peru, Italy, Czech Republic, South Korea.)

Quotable

“Covid-19 is the most severe global health challenge we have seen in our lifetime, and Johnson & Johnson is committed to help the world win the fight and be even better prepared for possible future pandemics.” —J&J chief scientific officer Paul Stoffels

For many Americans today, Johnson & Johnson is most closely associated with its fraught Covid-19 vaccine. But the vaccine is nowhere near J&J’s main product: Out of over $22 billion in first-quarter revenue, Covid-19 vaccines accounted for $100 million, or just above 2%. By comparison, Moderna and Pfizer have projected 2021 sales from their vaccines to be $18 billion and $15 billion, respectively, and both are anticipating additional booster shots.

The difference has to do with the number of doses (J&J has fewer delivery commitments) and the relative recency of J&J’s vaccine approval (late February). But as Annalisa Merelli reports, J&J’s shot also isn’t making money because it’s not supposed to. The company adopted a not-for-profit model for its vaccine, at least until the end of the pandemic.

How we emoji now

Covid-19 crushed some sectors of the global economy and buoyed others. Many of these shifts are apparent in transactions made on Venmo, a PayPal-owned payment platform for people in the US. David Yanofsky analyzed Venmo emoji use in over 68,000 transactions from March 2020 to March 2021. Here are some of our favorite findings:

- ❤️ was the most used emoji on Venmo in March 2020. One year later, its usage continues to climb.

- 🎉 and 🥳 are making a comeback as some of the world starts to emerge from the pandemic.

- Of all the emoji that appeared in at least 0.5% of transactions in March 2020, 😷, 🧻, and 🦠 were the least used in March 2021.

Essential reading

- The latest 🌏 figures: 148.2 million confirmed cases; 85.7 million classified as “recovered;” 1 billion vaccine doses administered.

- Face time: How to calm your anxiety about returning to the office.

- Face off: “Zoom fatigue” is worse for women.

- Face it: Getting a new bike right now is very difficult.

- Let the Games begin? How the Tokyo Olympics are forging ahead.

Our best wishes for a healthy day. Get in touch with us at [email protected], and live your best Quartz life by downloading our iOS app and becoming a member. Today’s newsletter was brought to you by Itika Sharma Punit, Katherine Foley, Samanth Subramanian, Lila MacLellan, Amanda Shendruk, Anne Quito, Annalisa Merelli, David Yanofsky, and Kira Bindrim.