Work isn’t a solo sport. Whether you work for yourself or someone else, you’re trying to please multiple masters. Rightfully so, as colleagues, clients, and connections can make or break how well we perform—and how we feel about it.

To understand how to communicate hard things, we consulted two writers who have made a career out of talking about emotions at work: Liz Fosselin and Mollie West Duffy. Fosselin and West Duffy have normalized emotions through their data visualization and straightforward, funny advice. We turned to their book No Hard Feelings: The Secret Power of Embracing Emotions at Work for advice on handling tough conversations—and emotions—at work.

No hard feelings

Tom Lehman and Ilan Zechory are the cofounders of Genius, a music-media company. The pair became fast friends at Yale, but the moment they stepped into a business relationship, they began to drive each other crazy. “Tom has this manic energy that will drive us forward but will also create wreckage,” Ilan explained to The New York Times. And Tom had to battle Ilan’s tendency to get glum.

Their differences might have been complementary. Instead, Tom and Ilan found themselves unable to strike a balance between being overly cautious and blindly forging ahead. And as they kept bickering during business strategy discussions, their relationship became strained. “We had always related to each other as friends,” Tom told us. “And that made it hard not to take disagreements about our company personally.”

Their differences came to a head one day when they got mired in Manhattan traffic a few blocks from Penn Station. Their train was scheduled to depart in minutes to DC, where they had an important meeting. When Tom started anxiously poking Ilan about how late they were going to be, Ilan asked the cab driver to stop, paid the fare, and stalked up the sidewalk toward the station. Tom was outraged that Ilan had so abruptly gone on without him.

Tom and Ilan managed to get on the train seconds before it pulled out of the station, but their relief quickly melted into fury. As they stood in the aisle snarling at each other, a new fear crept into Tom’s mind. “Very frequently when I talked to people whose businesses failed, it boiled down to ‘we couldn’t get along,’” he told us. “It was always interpersonal issues.” Something about his relationship with Ilan needed to change, or Genius might fail too. So Tom and Ilan decided to go to couples therapy.

Words as a window

“Every human will frustrate, anger, annoy, madden and disappoint us,” writes philosopher Alain de Botton. “And we will (without any malice) do the same to them.” Communication is one of the most powerful tools we have to effect change. That’s where the fifth new rule of emotion at work comes in: Your feelings aren’t facts.

Effective communication depends on our ability to talk about emotions without getting emotional. We often react to one another based on assumptions we never bother to look at more carefully. But the words people say are not always what they mean. As the psychologist Steven Pinker points out, “Words themselves are not the ultimate point of communication. Words are a window into a world.”

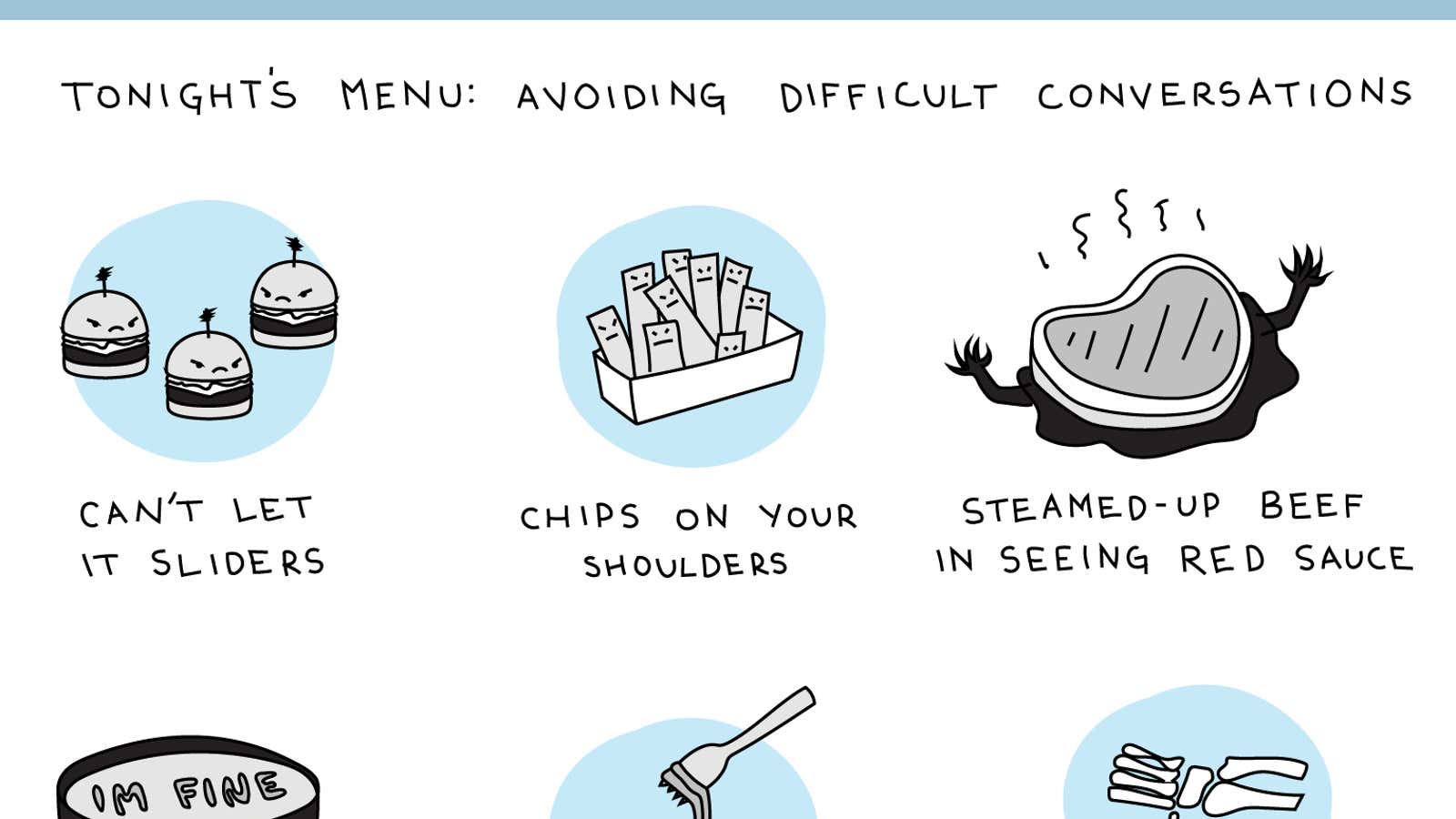

Difficult conversations can feel so daunting that we’re tempted to just avoid them. But if you avoid discussing an issue with a coworker, you deny them (and yourself) the opportunity to improve an uncomfortable situation.

Talking to each other

We’ve all seen a miscommunication devolve into a long-held grudge, just because neither party addressed the initial issue. As Tom and Ilan’s therapist taught them, “It’s better to discuss a problem, because it will surface anyway.”

Flagging and calmly discussing issues as they arose, instead of letting them fester, repaired Tom and Ilan’s relationship. But it’s also a mistake to rush into a difficult conversation: you’re more likely to make incorrect assumptions about the other person or just start venting. At worst, confronting a problem without a plan makes the other person feel attacked or have a meltdown.

To prevent the discussion from devolving, wait until you can do the following:

1. Label your feelings. (“I’m hurt.”)

2. Understand where those feelings are coming from. (“I’m hurt I wasn’t included on the email about Evan’s birthday celebration.”)

3. Feel calm enough to hear the other person out. A good rule of thumb is that if you think you have all the facts (“You didn’t CC me because you hate me”), you’re not ready to have a difficult conversation.

Speak up on the small things

To talk about feelings without letting them hijack the discussion, business school students at Stanford learn to use the phrase, ”When you ______, I feel ______ .”

“This avoids creating a victim and a perpetrator,” Chris Gomes, an alum who now runs a startup, told us. As Chris’s company scrambled to launch its website and close a big partnership, his cofounder Scott became increasingly impatient. Finally Chris told him, “When you cut me off, I feel dumb and annoying. It makes me nervous to come to you with questions.”

Tom also used this structure when Ilan showed up five minutes late to a meeting carrying a shopping bag filled with just-purchased books. “Your whole...stroll-in-late vibe, that makes me feel bad,” he said to Ilan.

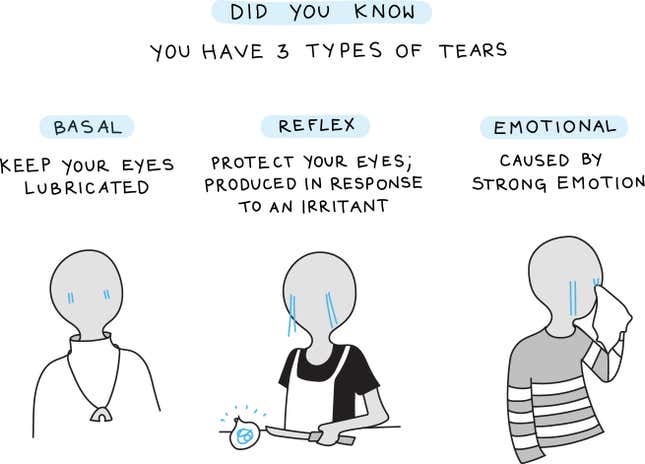

Crying at work

Don’t beat yourself up about crying on the job—it’s often a signal you care about your work. In fact, reframing your distress as passion makes others view your tears more favorably. During the 2016 presidential campaign, Hillary Clinton’s campaign staff cried so much that former communications director Jennifer Palmieri’s office became an ad hoc “crying room.” “No one I worked with—man or woman—thought anything of it other than that it was a human reaction to the inhumane crush a president and his or her staff endure,” writes Palmieri. “No stigma was attached to anyone who had to use the crying room.”

What if you see someone else crying? Understand that tears are not always a sign of sadness. Author Joanne Lipman found male managers often withhold feedback from female reports for fear of making them cry. Women do report crying more at work, but it’s usually out of anger or frustration. “Men don’t see it that way,” Lipman explains. “A woman crying in the office is the same thing as a man screaming and yelling and getting angry.”

Submit to the Best Companies for Remote Workers

Beyond giving room for emotions, how does your company prioritize its remote workers? Submit your company Friday, April 21st and see if they’ll make the ranking in Quartz’s Best Companies for Remote Workers 2023. GitLab, Andela, and ClickUp are among the 83 companies that made it on the list last year.

More stories for feelings on the job

🏃♀️ The best way to get teams to embrace change, according to science

🚧 3 barriers to playing well with others at work, and how to overcome them

😠 How to ensure conflict doesn’t erode employee trust

🗝 The key to happiness at work isn’t money–it’s autonomy

YOU GOT THE MEMO

Send questions, comments, and stories of anxiety at work to [email protected]. This edition of The Memo was written by Liz Fosselin and Mollie West Duffy and edited by Anna Oakes.