About 50% of Americans receive health insurance through their employer. That means where you work often plays an outsize role in determining the medical care you’re able to receive.

The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade will only further entrench this dynamic, with companies including Meta, Disney and JPMorgan Chase announcing new travel benefits aimed at helping employees access reproductive healthcare.

Reproductive-rights advocates say it’s commendable that companies want to help employees get necessary healthcare. But a system in which people can only have an abortion if they happen to work for an employer that’s willing to cover their travel costs and give them paid leave has dire implications for health and economic inequities in the US.

“I think, unfortunately, this will result in two tiers: the people who have the resources to get the care they need, and the people who don’t,” says Erika Seth Davies, CEO of the social impact firm Rhia Ventures, which is focused on women’s and reproductive health.

Anyone with a uterus, including middle-class and wealthy women, may be vulnerable to the fallout from the Supreme Court’s decision. But given that three-quarters of abortion patients are at or near the federal poverty level, lower-income workers (a group that includes a disproportionate number of women of color) are particularly likely to be impacted by the downfall of Roe.

They’re also less likely to work for companies that offer paid sick leave or paid family leave, let alone travel funding for abortion care. For this reason, it’s “wonderful but insufficient to do things that just take care of your own workforce,” says Shaina Goodman, director for reproductive health and rights at the National Partnership for Women & Families.

There are steps companies can take to try to mitigate the inequity of abortion access. They can take a close look at their political contributions, and consider long-term investments in abortion funds and reproductive justice organizations. As just one example, online dating companies Bumble and Match, both of which are women-led firms based in Texas, created relief funds in the wake of the state’s abortion ban, channeling money toward organizations that offer support for people seeking abortions.

And it’s not too late for companies to engage in political pushback against abortion restrictions. “If companies don’t want to be in this position,” says Davies, “they need to get on the phone with policy makers and ensure the Women’s Health Protection Act is enacted,” thereby guaranteeing that abortion rights are enshrined in federal law. —Sarah Todd

Read the rest of Sarah’s article to find out more about other issues raised by employers’ increased involvement in reproductive healthcare, from confidentiality concerns to the impact on labor organizing.

Five things we’re reading this week

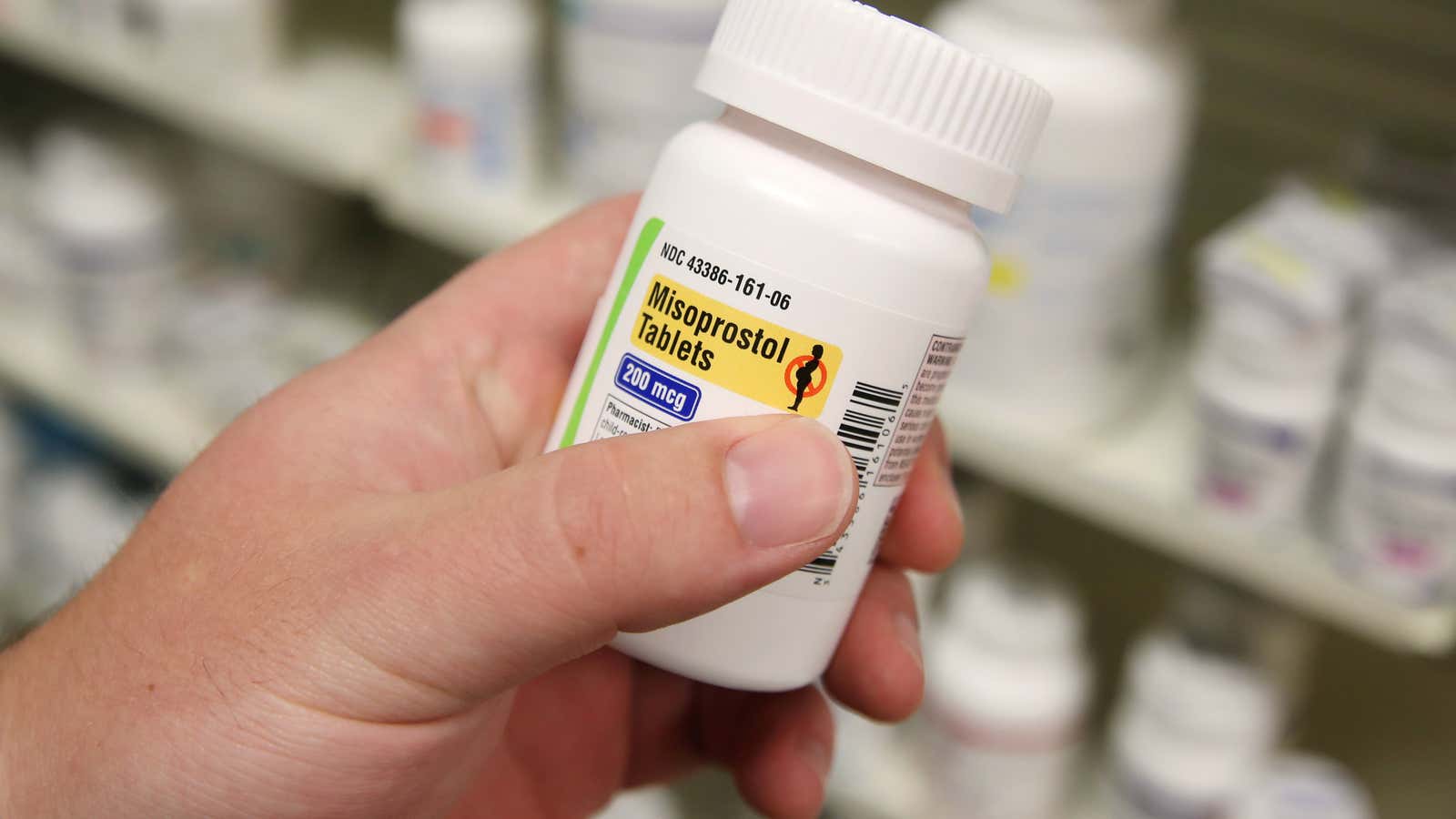

The US postal service is already one of the US’s main abortion providers. Half of all US abortions are induced by medicines which, since 2021, can be delivered in the mail.

Kate Bush’s royalties from Running Up That Hill are huge. Because Bush owns her masters, she made $2.3 million in streaming royalties in less than a month this year.

Walmart is offering doula benefits. The money for independent birth companions is aimed at lowering the risks involved with pregnancy and delivery.

These bankers trying to solve finance’s climate change problem. “I don’t think that people realize quite how screwed we are,” says one.

A chef from Sierra Leone won the Basque Culinary World Prize. Fatmata Binta says her favorite African dish is “Lachiri eh corsan,” steamed couscous made of sun-dried corn with plain yogurt fermented using the methods of the Fulani nomadic people.

30-second case study

This past May, workers at a Dollar General store in Apache, Oklahoma, were faced with the prospect of being stuck inside with no air conditioning. The forecast that day was above 100°F, and the temperature in the store had reached 85°F. So they quit.

“We have customers who won’t come in because it’s too hot for them,” the store’s assistant manager Rachel Minchow told local paper The Lawton Constitution. Employees had been submitting requests for the air conditioning to be fixed for close to two months, she said. “Customers complain that candy is melted. Every day, even if I’m just standing still, checking people out, I’m pouring sweat. That shouldn’t happen.”

The Dollar General employees went on to find work elsewhere. But as a broader issue, the risks of working in extreme heat are increasingly pressing as climate change sends temperatures in many parts of the world soaring. The problem impacts both people who work outdoors, such as agriculture and construction workers, and those who work in stores and factories with insufficient cooling systems.

The takeaway: It’s time for a global conversation about the intersection between climate controls and workers’ rights.

You got the Memo!

Today’s Memo was written by Sarah Todd and Cassie Werber and edited by Francesca Donner. The Quartz at Work team can be reached at work@qz.com.

Did someone forward you this email? Sign up for future installments here. Get the most out of Quartz by downloading our app and becoming a member.