For Quartz members—Looking under the Robinhood

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

Hi [%first_name | Quartz member%],

A handful of companies are thriving in the post-Covid-19 world. Apple. Amazon. Zoom. And…Robinhood. If you had asked in 2019 who the winners might be in an economy-shattering pandemic, who would have guessed a retail brokerage app? Welcome to 2020.

But first, this week’s recap: The US economy is going Xtreme, a colonial law is stifling speech in Hong Kong, and Nigerian scientists have identified seven lineages of SARS-CoV-2. We took a look at US passport power—in one emoji: 😬—but hey, at least carpools are coming back. In future news, Spotify might be killing the top 40, but the Long-Term Stock Exchange is ready to reform capitalism.

Your most-read story this week: A tool to practice overcoming “the mother of all biases.” And most relatable member goes to whoever is reading Six ways to trick your brain out of procrastination.

Okay, now open your Robinhood app and buy! Sell! Buy! Sell!

Have you heard this one?

Robinhood says it’s democratizing finance. It’s a great sales pitch—so great, in fact, that brokerages have been using it for decades.

Charles Merrill perfected that spiel after World War II, when he set out to take “Wall Street to Main Street.” His firm, Merrill Lynch, brought stock investing to an unparalleled number of regular people. Charles Schwab’s namesake brokerage, which slashed brokerage commissions in the 1970s, had a similar marketing gambit. E-trade did pretty much the same thing.

Robinhood is following a well-trod path to brokerage disruption—cut fees, target a new generation of traders, preach financial democratization—but the speed of the seven-year-old company’s rise is causing shockwaves in the industry.

Late last year, Robinhood helped spark a price war between the other big-time retail brokers. As commissions evaporated, profits took a hit, setting off an acquisition spree, with bigger fish gobbling up smaller ones. Charles Schwab is snapping up TD Ameritrade, while Wall Street titan Morgan Stanley set its sights on E-trade. Robinhood proponents say the company took price cuts to a new level by eliminating commissions, making the brand synonymous with retail trading in America.

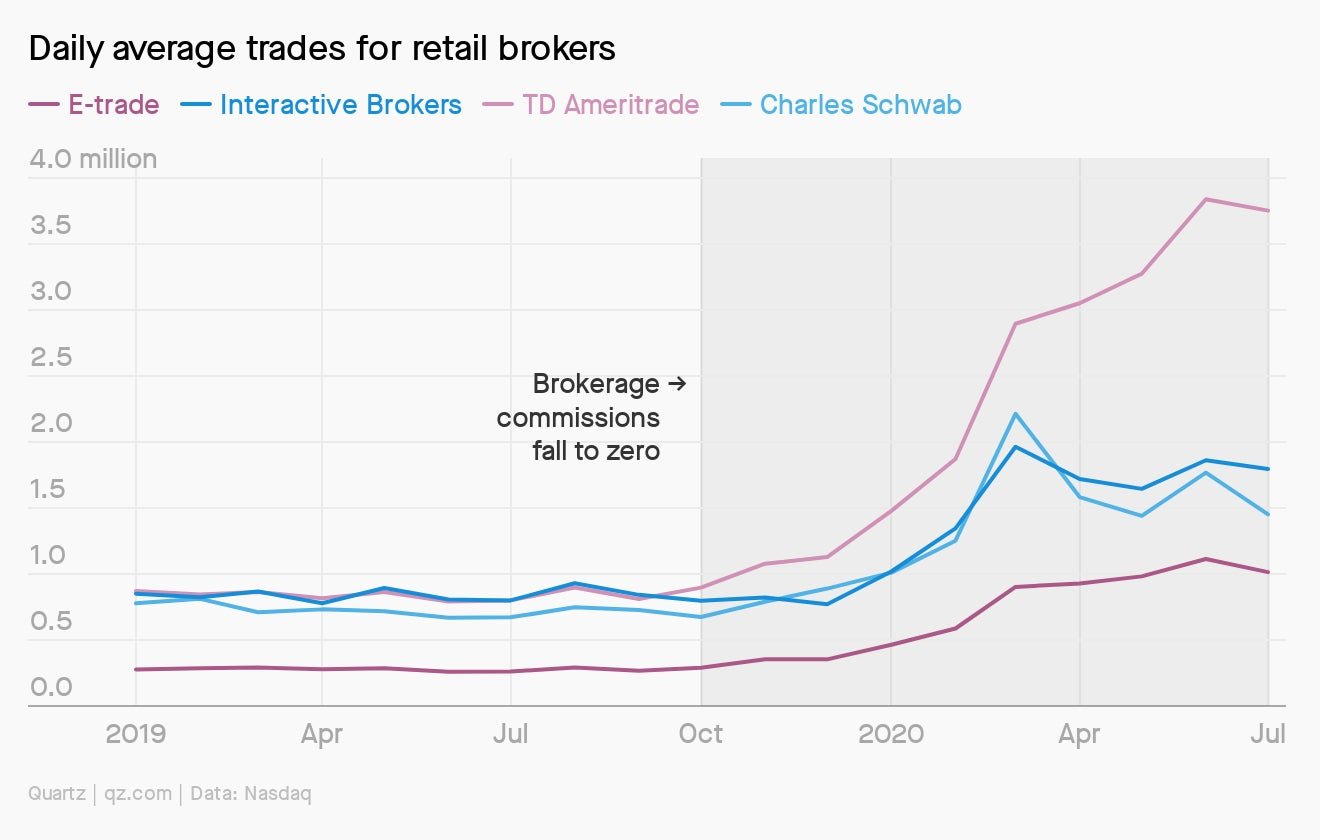

Consistent sales pitches aren’t the only long-term trend. In fits and starts, US stock trading has become more electronic and automated over the decades, and in doing so it has also gotten cheaper. (In the 1990s, Schwab charged as much as $80 for a trade through a live broker; last year the company eliminated commissions). Each step of the way, as trading costs go down, trading volumes have tended to go up.

Last year was no exception—commissions went away and trading volumes blew up. By June 2020, Robinhood had upwards of 4.3 million daily average trades, more than all the other brokerages in this chart. (Other factors, like the advent of fractional share trading and stay-at-home orders as a result of the pandemic, have also given trading a boost.)

Finding fresh meat

Instead of charging commissions, one of the main ways Robinhood makes money is by working hand-in-glove with market makers, selling its customers’ orders to large high-frequency trading outfits (HFTs) like Citadel Securities, Two Sigma Securities, and Virtu Financial. These firms turn a profit the same way the foreign-exchange booth in an airport does: on the gap between the bid and the offer. Robinhood, meanwhile, gets paid for its customers’ orders, known as “payment for order flow.”

Why would a trading firm pay to execute trades for Robinhood, or any retail outfit? Let’s consult the Quartz time machine:

The everyday investor is less informed and trades differently than the pros who, in theory, move in and out of assets more efficiently. Retail and institutional trades may flow in opposite directions, which is great for market makers who can provide bids to buy for one and offers to sell for the other. It’s also less risky: When trading on a public exchange, market makers have to compete with other sophisticated traders, as well as large investors who may buy or sell large chunks of shares, sending shockwaves through prices.

In other words, retail customers are fresh, red meat. As James Angel, a professor at Georgetown University, told Quartz: “You really don’t want to be playing poker with people who are better than you are.” The HFTs pay to sit at the amateur table.

A fair trade?

Just about every big US retail broker, from Schwab to TD Ameritrade, makes money on order flow, a practice that goes back decades. (You can read more about it here and here.) But while US regulators seem to have blessed the practice, it remains controversial.

Some officials worry that paying for orders incentivizes brokers to send stock trades to the market maker that pays them the most, rather than giving users the best trade execution. Others argue that trading is cheaper than it has ever been, and say customers are getting a better deal. All of Robinhood’s market makers pay the company the same rate, which is designed to remove conflicts of interest.

In 2019, Robinhood was hit with a fine related to getting its customers the best deals for their trades. This year the Wall Street Journal reported that Robinhood’s payment for order flow practices are under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission. Of the report, a Robinhood spokesperson said, “We strive to maintain constructive relationships with our regulators and to cooperate fully with them.”

Glitches in the make-rich

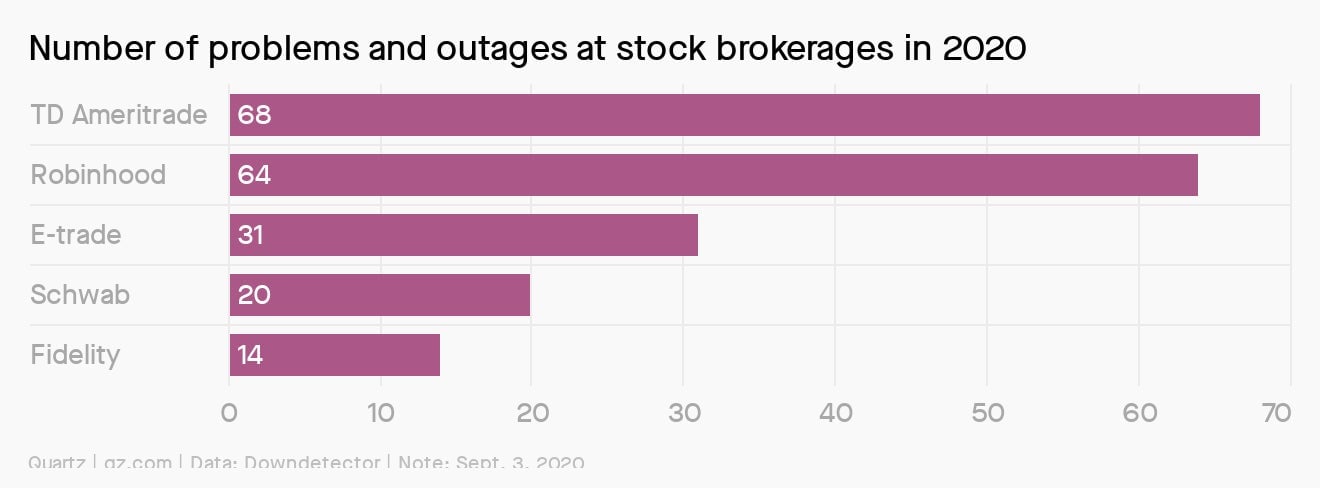

There have been other hurdles on Robinhood’s road to success. It experienced major outages in March as markets were roiled by the pandemic, leaving customers unable to trade during some of the biggest price swings in history. A lawsuit claims the company “should have provided a financial services platform that would have been robust enough to handle that trading volume.”

But Robinhood isn’t the only platform that wobbled. This year, brokerage TD Ameritrade has suffered more outages than Robinhood has, according to data from Downdetector. (Both companies are now focused on increasing capacity and bolstering testing.)

Robinhood has faced other controversy as well. Alex Kearns, a 20-year-old who used Robinhood to trade options, committed suicide over the summer. Reports indicate that Kearns, who said in a note that he had “no clue” what he was doing, may have misunderstood the losses on his account.

Critics say Kearns’s tragedy shows the brokerage is courting young traders who are unprepared for the risks they’re taking, and may have little understanding of assets like options, a financial derivative that can be used to hedge or speculate on stocks.

Robinhood’s founders said they were devastated by the suicide. The company has since updated its options offering, is widening its educational resources, and has doubled the size of its customer support team.

The brains

Robinhood co-founders Vladimir Tenev and Baiju Bhatt say they were inspired by the Occupy Wall Street movement, which sprung up in 2011 in Manhattan to protest economic inequality. Around that time, the duo ran a company called Chronos Research, which sold software to HFTs.

When I met Tenev about a year ago in London, I had a mental picture based on the résumé he shares with Bhatt: Stanford physics whizzes turned startup billionaires. I partly expected him to be cocky and aloof. Likely “pumped” about something. Or else the exact opposite—too smart and awkward to have a regular conversation over coffee.

Tenev wasn’t that. He was (for whatever reason) much taller than I expected. Better looking, and more easy going. He came across as a tad humble, and the conversation, as it tends to in other interviews, veered toward his wife and daughter. Tenev may have co-founded a company with 13 million customers and an $11 billion valuation (up from $5.6 billion two years ago), but he doesn’t seem like a Silicon Valley stereotype, or is at least able to fake it for an hour.

How to (not) pick ‘em

The brokerage industry’s “financial democratization” message can be overhyped, but trading has indeed gotten far cheaper and more accessible. The key to accumulating wealth in financial markets, according to a number of experts, is to do it in the unsexiest way possible. Here are two basic tips:

📅 Don’t be a stock picker. Instead, buy a diversified portfolio of stocks or bonds through an index fund or an exchange-traded fund. Investing is measured in years, not hours or days.

💰 Even long-term investing has risks. Make sure you have ample savings before plowing money into the S&P 500. If you dial up the risk, make sure it’s money you can part with if necessary.

Essential reading:

- This is your brain on Robinhood

- How Ponzi mastermind Bernie Madoff enabled the US retail trading boom

- Inside the hormones, politics, and technology fueling a global stock market bubble

- Robinhood is making far more money from the options boom than from stocks

- Robinhood is getting paid more than its rivals for stock trades

- How the retail trading boom is shaking up the US stock market

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for a democratized end to your week,