Welcome to Part Two of our new member email series—this one should feel familiar. For a year now we’ve sent you short profiles of important companies, and that will continue! Stay tuned for more in your inbox on Friday and Saturday, and read more about our new member emails here.

Hi Quartz members,

Say you’re interested in working in tech, but you live in Bakersfield, a city of about 400,000 people in California’s agriculture-dominated Central Valley. Before the pandemic, unless you were willing to move, positions in software development or data science were a long shot: Your area’s share of digital jobs is already low, and shrinking.

But post-pandemic, more tech companies are hiring remotely; that means time you spend picking up tech skills from Bakersfield is now more likely to pay off. At least that’s how Jeff Maggioncalda, CEO of online education platform Coursera, sees the company’s prospects after Covid-19: More remote work means more remote learning.

Since its founding in 2012, Coursera has published nearly 4,000 courses from top universities, mostly free to watch, and its vision is a world where everyone has access to quality education. After nearly a decade of skeptics calling that model naive, the company went public in March at a valuation of $5.9 billion. Between the end of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021, Coursera’s registered users grew 87%.

Before the pandemic, “the benefit of learning new skills was related to how many opportunities you have near you,” Maggioncalda told Quartz. But as remote work decouples your job prospects from where you live, “the value of you learning new skills goes way up.”

There are some problems with this vision. It requires work-from-anywhere jobs, not just two-days-a-week-in-the-office. It presumes that employers will trust credentials from Coursera and its peers. And it emphasizes skill development as the path to economic opportunity, despite the many other barriers to better jobs and higher wages. (It’s hard to blame Coursera for that last one, though.)

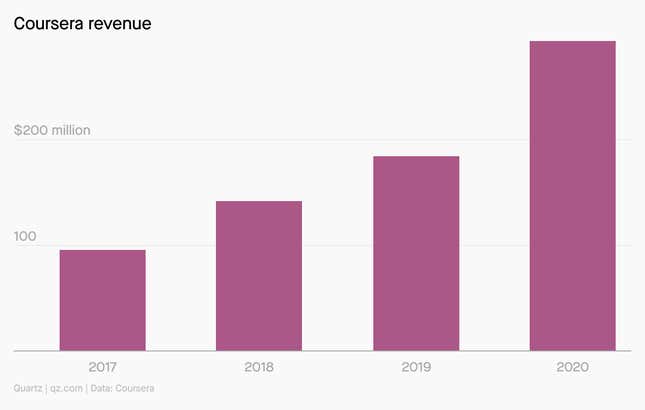

The pandemic was “like a time skip,” says Dhawal Shah, an edtech analyst and founder of ClassCentral. Online education saw two years of progress in two quarters, he says, and no one benefitted more than Coursera. Its revenue increased 63% from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of this year.

The company is also embracing its own vision: Employees can now, by and large, work from anywhere Coursera has a business entity. “We’re going to be a totally different kind of company when we go back to the office,” Maggioncalda says. He’s betting that lots of others will be, too.

How Coursera makes money

- Coursera’s courses come from partner institutions—mostly selective universities like The University of Pennsylvania, but also a small number of companies, including Google and Microsoft.

- 59% of its revenue comes from consumers. The company has 87 million registered learners, and while many courses are free to audit, users pay to receive certificates and other credentials.

- 28% of its revenue comes from its “Enterprise” business, which includes businesses paying to offer Coursera courses to employees and universities using its platform for remote education.

- 13% comes from degrees offered through the platform. Tuition is split between Coursera and the university offering the degree. (50/50? 90/10? Coursera doesn’t disclose.)

Coursera’s founders

Daphne Koller (☝️ on the left) joined the Stanford Computer Science department in 1995, and in 2004 won a MacArthur “genius” grant for her research applying statistics to artificial intelligence. A few years later, while hearing a talk about the nascent video platform YouTube, she had the idea that would form the basis of Coursera.

“All of a sudden it came to me,” Koller said in a 2012 interview with Computer magazine. “Instead of delivering the same lecture I had been giving for 15 years, telling the same jokes at the same time, maybe we could flip the classroom: Record my lectures, with interactive quizzes, and make them available to students in a format that is much more engaging than a traditional lecture-format class.” She piloted the idea in 2010 within Stanford.

A year later, Stanford decided to use the software from Koller’s pilot to make three of its computer science courses available to the public: Machine Learning, Introduction to Artificial Intelligence, and Introduction to Databases.

Andrew Ng (☝️ on the right ) was an associate professor in the same department and taught the Machine Learning course Stanford made public. He’d also developed his own software for sharing lectures, which Stanford combined with Koller’s for the experiment. 72,000 students registered for his course, 40% of whom lived outside the US.

That Stanford experiment was a turning point for edtech. Koller and Ng were convinced of the potential to expand online education, but felt it would be easier to do outside Stanford. So they teamed up to found Coursera. (Sebastian Thrun, the Stanford professor behind the AI course that was made public, founded his own online learning company, Udacity, in 2011.)

Neither Koller nor Ng work at Coursera today. In 2016, Koller left to join Calico, a startup within Google focused on slowing aging. In 2018 she founded Insitro, a startup applying machine learning to drug discovery. Ng left Coursera in 2014 to become chief scientist at Baidu. He left in 2017 and founded LandingAI, which makes software for machine learning operations. Coursera’s current CEO, Maggioncalda (☝️ at the center above) has been there since 2017.

A brief history of remote learning

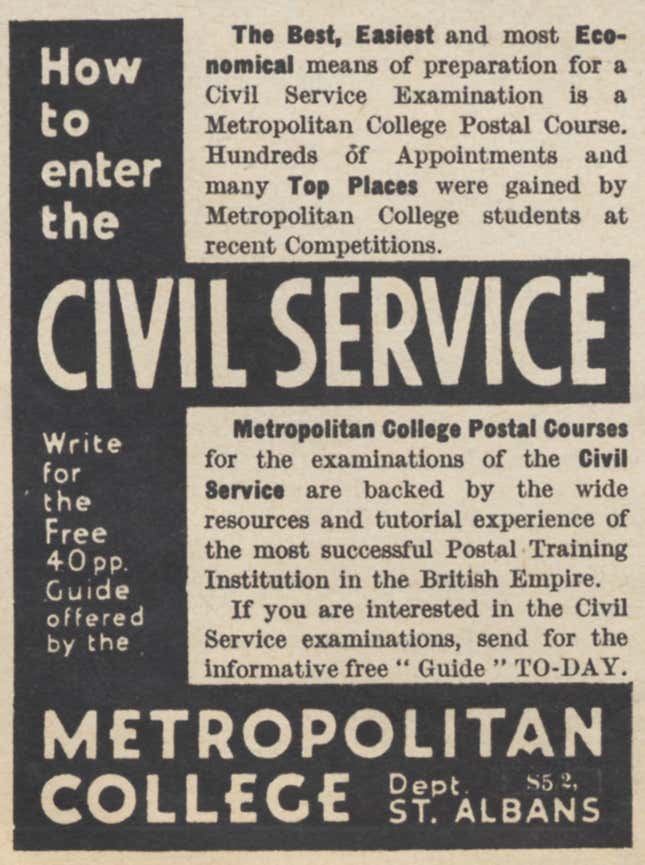

1728: An ad for the first correspondence course appears in a Boston newspaper, offering instruction via mail. The topic: shorthand, which makes sense if you consider all the writing involved in teaching by mail.

1779: The University of Warsaw launches a correspondence course in physics, an exception to the general rule that these courses focus mostly on technical skills.

1873: The first school dedicated to distance learning—“Boston Society to Encourage Studies at Home”—is founded by Anna Eliot Ticknor. It offers women access to higher education.

1892: The University of Chicago starts offering correspondence courses.

1988: Harvard Business School sells VHS tapes of professor Michael Porter teaching his popular class on corporate strategy, one of many universities selling taped lectures in the 1980s.

1990: The Teaching Company is founded in Virginia and launches “The Great Courses,” lectures on cassette tape and VHS.

2004: A young hedge fund analyst in Boston named Sal Khan starts tutoring his cousin Nadia remotely. In 2008, based on the lessons he records for her, he forms Khan Academy.

2007: Apple launches iTunesU, a section of its platform dedicated to recordings of university lectures.

2010: Stanford’s experiments with online learning lead to the founding of Coursera and Udacity.

Hit list

Here are the most popular Coursera courses for the first quarter of 2021:

- 🤖 Machine Learning (Stanford University)

- 😊 The Science of Well-Being (Yale University)

- ✍ English for Career Development (University of Pennsylvania)

- 🇰🇷 First Step Korean (Yonsei University)

- 🤓 Learning How to Learn (McMaster University, UC San Diego)

- 💸 Financial Markets (Yale University)

- 😷 COVID-19 Contact Tracing (Johns Hopkins University)

- 🐍 Programming for Everybody (Getting Started with Python) (University of Michigan)

- 🧠 Introduction to Psychology (Yale University)

- 💻 Technical Support Fundamentals (Google)

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or companies you want to know more about.

Best wishes for an educational to your week,

Walter Frick, executive editor

(Coursera course I most recommend: Model Thinking)