A blockbuster holiday

Part ritual, part fiesta, the Day of the Dead is the Mexican version of All Souls and All Saints days, observed on Nov. 1 and 2 by the Catholic church. Like the celebration of those holy days in Europe and elsewhere, it also involves trips to the graveyard and candles to honor the dearly departed. But over centuries, Mexico’s Día de Muertos has evolved into a distinct tradition with its own ghoulish iconography. For many Mexicans, it embodies the national spirit: an alluring blend of millenary indigenous lore, color, and whimsy.

But like any holiday, the Day of the Dead is more complicated than it appears. Its prehispanic origins are not as clear-cut as some make them out to be. And almost from the start, the holiday has been as much an occasion to sell goods and services like masses, sweets, and more recently, Doritos, as one to commemorate deceased relatives.

To be sure, Día de Muertos is grounded in tradition. But these days that tradition includes big-box store seasonal merch and a parade inspired by a James Bond movie.

Care to join us in the underworld? Let’s cross over.

By the digits

410,000: Number of tourists expected to attend Mexico City’s Day of the Dead celebrations in 2022

$201 million: Estimated economic impact from the celebrations

80%: Expected hotel occupancy during the events

5 million: Number of cempasúchil, or marigold, plants that will decorate Mexico City

40%: Increase in cempasúchil production from last year in Xochimilco, a Mexico City district

$35: Estimated cost to set up a modest altar for the dead

21%: Increase in the price of elements for an altar for the dead in 2022 vs. 2021 due to inflation

A holiday of one’s own

If you go by the Mexican government’s promo (link in Spanish), the Day of the Dead is a prehispanic tradition based on an ancient Mexican belief of life and death as parts of a whole, not opposites—a concept Spanish colonizers just couldn’t get, as the publicity points out.

But some anthropologists (Spanish) disagree. The skulls that have come to symbolize the holiday don’t stem from prehispanic imagery, but from Catholic relics—saints’ bones and other remains that were put on display on All Saints Day in medieval Europe. As for the festivities, records show they were orchestrated by Mexico City officials as early as the 1800s, and included puppet shows, carousels, and all kinds of food stalls.

In these researchers’ telling, the links to Aztec and other prehispanic cultures came later, during a bout of populism in the 1930s in which politicians and intellectuals sought to cut ties (Spanish) with both Spain and the US. They gravitated towards what made Mexico different from those powers—its indigenous past—and injected that into existing traditions, including the Day of the Dead. More recently, local governments have deployed that interpretation of the holiday, staging “authentic” celebrations (Spanish) to attract tourists.

So, is there a real version of the Day of the Dead? Not really. It’s a work in progress. “Rituals, just like us, are perishable and modifiable, otherwise anthropology and history would have nothing to do,” wrote researcher Elsa Malvido in an essay published by Mexico’s history and anthropology institute.

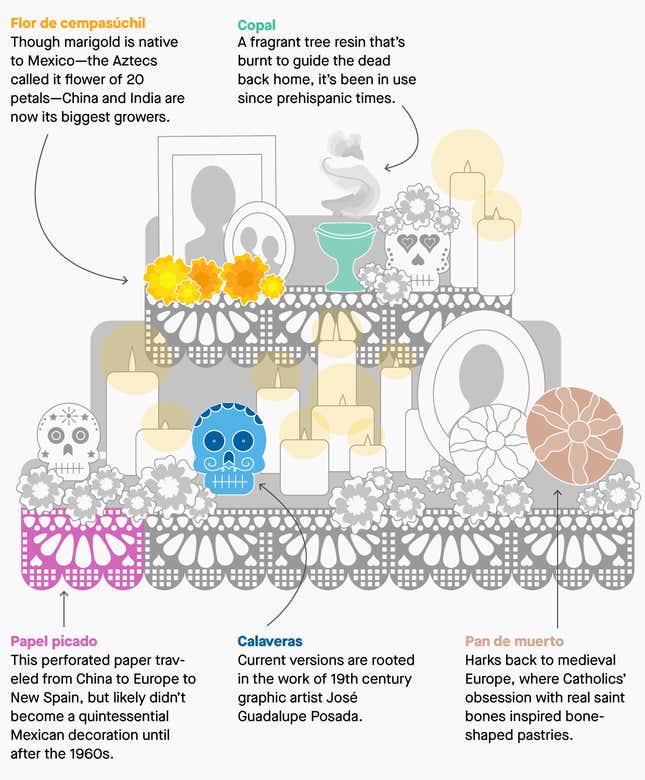

Around the world in an altar

The center of the Day of the Dead tradition is the altar de muertos, a tiered display meant to lure its deceased honorees with their favorite earthly pleasures—from tequila to mole. But altars also share common elements, a jumble of items that speaks to the holiday’s centuries-old, global evolution.

Brief history

11th century: The abbot of Cluny establishes Nov. 1 as All Saints day, a celebration to commemorate Catholic martyrs.

1521: After conquering Mexico, Spaniards import the festivity to what was then called New Spain.

1740s: Vendors start peddling sugar figurines known as alfeñiques (originally a Muslim treat from Moorish Spain) during All Saints celebrations in Mexico, already referred to at the time as the Day of the Dead.

1972: Chicano artists hold the first public Day of the Dead celebration in Los Angeles, bringing the Mexican tradition north of the US-Mexico border.

2008: Unesco adds the Day of the Dead as practiced by Mexico’s indigenous communities to its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

2017: Disney releases Coco, a tale of a Mexican boy’s journey into the infraworld that grossed more than $800 million at the box office. The film won two Oscars, for best song and best animated film.

Quotable

“To the people of New York, Paris, or London, ‘death’ is a word that is never pronounced because it burns the lips. The Mexican, however, frequents it, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, celebrates it; it is one of his favorite toys and most steadfast love.”

—The Labyrinth of Solitude (pdf), Octavio Paz

Take me down this 🌼 path

Mexico was once the world’s biggest producer of marigolds, or Tagetes, which includes dozens of species (Spanish) native to Central and South America. The flower, whose color ranges from yellow to cherry, has a distinct smell believed to guide the dead back home.

But in addition to its Day of the Dead duties, cempasúchil renders dyes used in health supplements and to color egg yolks. The global market for those dyes, known as carotenoids, is worth $2 billion now, and expected to reach $2.7 billion by 2027.

Starting the late 1990s (Spanish), marigold production migrated to China where labor was cheaper for flowers harvested by hand. The plants grown in Mexico now are mostly used for decoration (Spanish). The country has tried to get back into the marigold business, with local researchers creating a new variety (Spanish) for industrial use. National production has also jumped over the past few years, but much of it sprouts from imported seeds (Spanish).

Ahead of the Day of the Dead, farmers are urging shoppers to pick Mexican (Spanish) over Chinese varieties for their altars: The native flowers are taller, their blooms bigger, and their color more vibrant.

Pop quiz

Which of the following Day of the Dead celebrations is not held on Nov. 1 and 2?

A. Undas

B. Food of the spirits

C. Grateful Dead Day

D. Day of the Blessed Souls

Find the answer at the bottom.

What if shortened work weeks weren’t just for holidays?

If you had an extra day of work off this week, maybe you’d spend it making sugar skulls or pan de muerto, or collecting the brightest marigolds for your altar.

The idea of a four-day work week may not be a hypothetical—more companies and governments are experimenting with the setup, and the results are surprising. Find out more in our new podcast episode that drops tomorrow (Oct. 27).

🎧 Listen to Work Reconsidered on: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

A Bond-new tradition

Inspired by the Day of the Dead craze, director Sam Mendes opened his 2015 James Bond film Spectre with a parade celebrating the holiday in Mexico City. The epic sequence, which follows a skeletal Daniel Craig as he navigates a sea of calaveras, in turn spurred the local government to host a new annual celebration: the Desfile de Día de Muertos. Tradition is a living, breathing thing.

Poll

Which spooky holiday would you rather celebrate?

Either way, we can agree there needs to be sweet treats.

💬 Let’s talk!

In last week’s poll about Edgar Allan Poe, 66% of you said you had no idea what Homer Simpson crying over Marge had to do with The Raven. Well, even the Simpsons couldn’t resist doing their own interpretation of the story.

🤔 What did you think of today’s email?

💡 What should we obsess over next?

Today’s email was written by Ana Campoy (requests her relatives leave mezcal instead of tequila), visualized by Amanda Shendruk (is ready for a siesta), and edited and produced by Morgan Haefner (wants an order of tamales).

The correct answer to the pop quiz is C., Grateful Dead Day. The day is definitely real though—it’s celebrated on May 8, commemorating one of the band’s iconic concerts.