Hi Quartz members,

Everything’s inflating these days—including thought leadership. A mere “debacle” is no longer enough; the word in the wind is “polycrisis,” fanned to a fever-heat popularity by the historian-turned-pundit Adam Tooze.

No doubt you’re running into the term everywhere: the headlines in the pink papers, the briefings of important policymakers, Twitter, book titles, climate change agendas (pdf). The notion behind “polycrisis” is that humanity’s problems—economic uncertainty and inequality, political instability, and especially the threat of climate change—need to be understood through their interactions with each other.

And that’s not a bad frame. But is it a novel one? Does it help diagnose our problems better, let alone address them?

Tooze, at least, says yes, because “it no longer seems plausible to point to a single cause and, by implication, a single fix,” to the world’s problems, as it might have in the past. But that was never plausible. The ills of the 1980s could no more be solved by the market alone—or the state alone, or civil society, or your fix of choice—than they can be today (or ever, for that matter). And when champions of the term insist that this polycrisis is the first multi-causal crisis in history, it sounds, well, ahistorical (see below).

The other novelty in Tooze’s analysis is how global development and climate change raise the stakes of our economic and political difficulties. The increase in climate-related disasters is new, even if it is a path we set off on 200 years ago. But if potential global self-destruction is the underlying requirement of a polycrisis, we’ve been there since Hiroshima.

Other definitions offer more specificity, focusing on multiple sources of systemic risk amplifying each other and breaking down a shared understanding of the problems—what Tooze calls a “flailing inability to grasp our situation.” You might call that the human condition.

Arguably, we’ve never had more clarity about humanity’s threats and how to respond to them. We developed vaccines to the covid-19 pandemic on the fly, which wasn’t possible a century ago during the Spanish Flu epidemic. Economic policy is far from perfect, but recession-fighting and safety nets have come a long way since the Great Depression. Climate change (and what must be done to fight it) is better understood today than ever.

If anything, our chief crisis is a social one—a paralysis that fails to push solutions forward thoroughly in the face of knotty problems. Giving that complexity a name is only a start. Businesses and governments know already that there isn’t a single fix to our problems. But a better diagnostic concept would help them understand where to start.

The job of an intellectual in a complex world is to clarify, and it’s not clear that “polycrisis” means anything more than its Greek roots: We’ve got a lot of problems.

GREAT POLYCRISES IN HISTORY

Is the polycrisis new? Well...

💀 World War I, 1914-1918. The global conflict that kicked off modernity involved a technological arms race, geopolitical competition, and new political ideas about self-government. But it also took place during a global cold snap that increased mortality and set the stage for the spread of the Spanish Flu around the world, which is thought to have killed one out of every 100 people on the planet.

💀 The Great Famine in India, 1876-1877. The Madras famine, which killed between 6 and 10 million people in India, was part of a larger weather phenomenon that ruined harvests across the global South. Its effects were accelerated by the British East India Company, which continued economic exploitation and blocked relief efforts.

💀 Thirty Years War, 1618-1648. This wasn’t just a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics. The wars that laid waste to central Europe were chaotically overlaid on dynastic disputes, new forms of political propaganda, and the rise of absolutism, while the Little Ice Age wreaked havoc with harvests. Oh, and there were plagues.

💀 The Native American Genocide, 1491-present. European colonialism emerged from political, economic, and religious motivations, and was driven by technological leaps. But the polycrisis for indigenous people also included infectious diseases to which they had no immunity, and ecological catastrophes driven by the resultant population collapse.

THE BIRTH OF A WORD

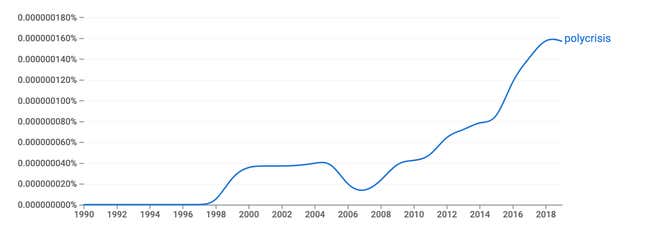

Tooze heard the term “polycrisis” from Jean-Claude Juncker, the former European Commission president who, in 2018, used the p-word to refer to the EU’s challenges of migration, climate change, debt and economic growth—although he also said that Europe had “surely turned the page from this so-called ‘polycrisis.’” So much for that.

Juncker, in turn, borrowed “polycrisis” from the French theorist Edgar Morin, who co-authored a 1999 book that introduced the idea. Morin, who fought with the French Resistance during World War II, did much of his subsequent intellectual work on complex systems across different disciplines.

Per Google’s corpus of English language publications, the term was briefly in vogue at the turn of the century (perhaps a Y2K vibe) but really took off following the 2008 financial crisis.

ONE 🚨 THING

Either Collins English Dictionary didn’t get the “polycrisis” memo or it decided to be a maverick. In choosing its Word of the Year 2022, Collins plumped for “permacrisis”—a term defined as “an extended period of instability and insecurity.” Sounds about right, especially given how many of Collins’s other candidates for Word of the Year all emerged from one or the other of the world’s current crises. Here are a few:

Warm banks: The winter equivalent of food banks: locations where those unable to heat their homes can gather during a cold snap.

Sportswashing: The athletic equivalent of “greenwashing,” in which countries stage big sporting events to cover up their poor human rights or climate records.

Partygate: The British scandal involving government officials and civil servants meeting for long, boozy parties during times of strict covid lockdowns. Its repercussions brought down prime minister Boris Johnson.

Lawfare: The use of lawsuits to bully or trip up a rival.

Quiet quitting: As Collins describes it: “doing no more work than one is contractually obliged to do.” A product of the pandemic age, quiet quitting has been framed as a solution to burnout, or as a reaction to corporate monopolization of employee time.

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- Marvel directors: There will never be another $1 billion opening. “Avatar 2” and DC: Hold my cape

- The “Lawyers of Kleenex” are taking a soft approach to the hard realities of genericide

- China is bringing industrial policy to the metaverse

- As clocks fall back, America’s plan to make daylight saving time permanent has made no progress

- Ambition: Can giving up be good for you?

- What does the booming sperm-donor industry owe to people it helps conceive?

- The companies responsible for the $1.5 trillion-a-year US opioid crisis will pay a total of $53 billion for it

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

🤑 The crypto vote. Amid news that American billionaires spent a record sum on the upcoming US midterm elections, there’s another constituency that’s trying to bite off a crumb of influence: crypto execs. As Vox reveals, crypto trade groups are working to form a Web3 voting bloc to push pro-crypto candidates into power. The crypto coterie, still in its nascency, is using the midterms as a test round, but could become a real political contender in future elections.

🪖 Military emissions. An opinion piece from Nature points out that military emissions are missing from the global climate agenda. According to some estimates, armed forces could be contributing anywhere from 1% to 5% of global emissions, but there are no international agreements, tracking methods, or regulatory standards to hold them accountable. The authors lay out four points in their call to action to decarbonize militaries.

🥫 Art attacks. In recent months, there have been several incidents in which climate activists attacked venerated pieces of art: a Van Gogh got a can of tomato soup, a Monet was smeared with mashed potatoes, and a Vermeer found itself glued to a man’s head. The Atlantic goes into why the efficacy of these protests is questionable, not only from a social science perspective, but also because the whole optics are a bit…cringe. And ultimately: “Aesthetics matter in politics.”

🧠 Hey, you listening? More adults are getting diagnosed with ADHD, and medicated for it, too, with Adderall prescriptions in the US jumping 16% between 2021 and 2022. The New Statesman explains that underdiagnosis is a big reason behind the increase in ADHD adults, but other factors could be at play, including the internet’s frenzied attention economy, the lasting impacts of the pandemic, and the increasing struggle to meet unrealistic cultural expectations.

🐚 Cool as shell. Eva Donckers, an enterprising reporter from Vice, stumbled across the website for the Royal Belgian Association of Conchology. Soon enough, she found herself attending The Shell Show, an international shell collectors convention that has run in towns around Antwerp for over 30 years. A delightful story and photoset documents the many characters she encounters, including Eddy, a homicide detective by day and predatory snail collector by night.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a crisis-free weekend,

— Tim Fernholz, senior reporter, space, economics, and geopolitics

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck, Alex Citrin-Safadi, and Samanth Subramanian