The obstinate war

Any hopes that Russia would quickly end its invasion of Ukraine have now given way to the reality of a long, grinding war

Hi Quartz members!

When Russian troops marched into Ukraine, one of two outcomes seemed possible. The first: The war would end quickly, either through a devastating Russian occupation or a Russian defeat at the hands of a Western coalition. The second: The war would turn into a long affair of attrition, resulting in tragic losses of life and property, and a dire reshaping of the world economy.

A year on, the war hasn’t ended, and the destruction has come to pass: at least 8,000 Ukrainian civilians dead, millions displaced, and, by one count, $138 billion in damaged infrastructure. But the most calamitous forecasts—a worldwide wheat shortage; a collapsed Russian economy; a European winter of blackouts—never transpired. Not to tempt fate, but: What happened? Were the predictions overblown? Or, after two years reordering itself during the pandemic, did the world manage to adjust to a lengthy war, as clinical as that sounds?

The truth is that the predictions did materialize; they were just, to paraphrase William Gibson, unevenly distributed. The great European energy-shortage-to-be is a fine example. There were no widespread blackouts, partly because of a mild winter, but also because European countries spent more than $800 billion shielding their citizens from power deficits. That expenditure will hurt governments and taxpayers in the near future, even if some of it was in the service of a long-term transition to green energy. And high energy bills did claim their victims. A new study published in Nature Energy estimates that higher energy costs could push between 78 million and 141 million people into extreme poverty. As ever, the real pain will be felt by the people rendered least visible by the calculus of global economics.

HOMEWARD BOUND

Much more manifestly, the people of Ukraine bear the direct brunt of the war. At least 8 million people have left the country since the start of the war, and another 5.4 million are internally displaced, according to the UN High Commission for Refugees. As Quartz’s Nate DiCamillo and Cassie Werber discovered, though, many millions of them are going back to Ukraine. For one thing, life as a refugee is hard. But for another, they’re emboldened by Ukraine’s doughty defiance, and they also want to be a part of that resistance.

To recover their old lives, they will have to figure out afresh how to make ends meet. The Ukrainian hryvnia has buckled, and Ukraine’s GDP has declined by over 30%. The government has provided financial assistance to the needy and to families of people fighting on the front lines, but it recently had to cut the pay of soldiers because of the government’s stretched budget.

It’s a circular dilemma: The economy will improve if Ukrainians return in significant numbers, but many of them will, very understandably, delay their return until the economy improves. “We need to raise up, and to support business here, to support economics,” one returnee told Quartz. “We understand that it’s a very bad situation, but we need to do something, we need to create something here; to try, and to show another view: that life here exists.”

FORTRESS RUSSIA

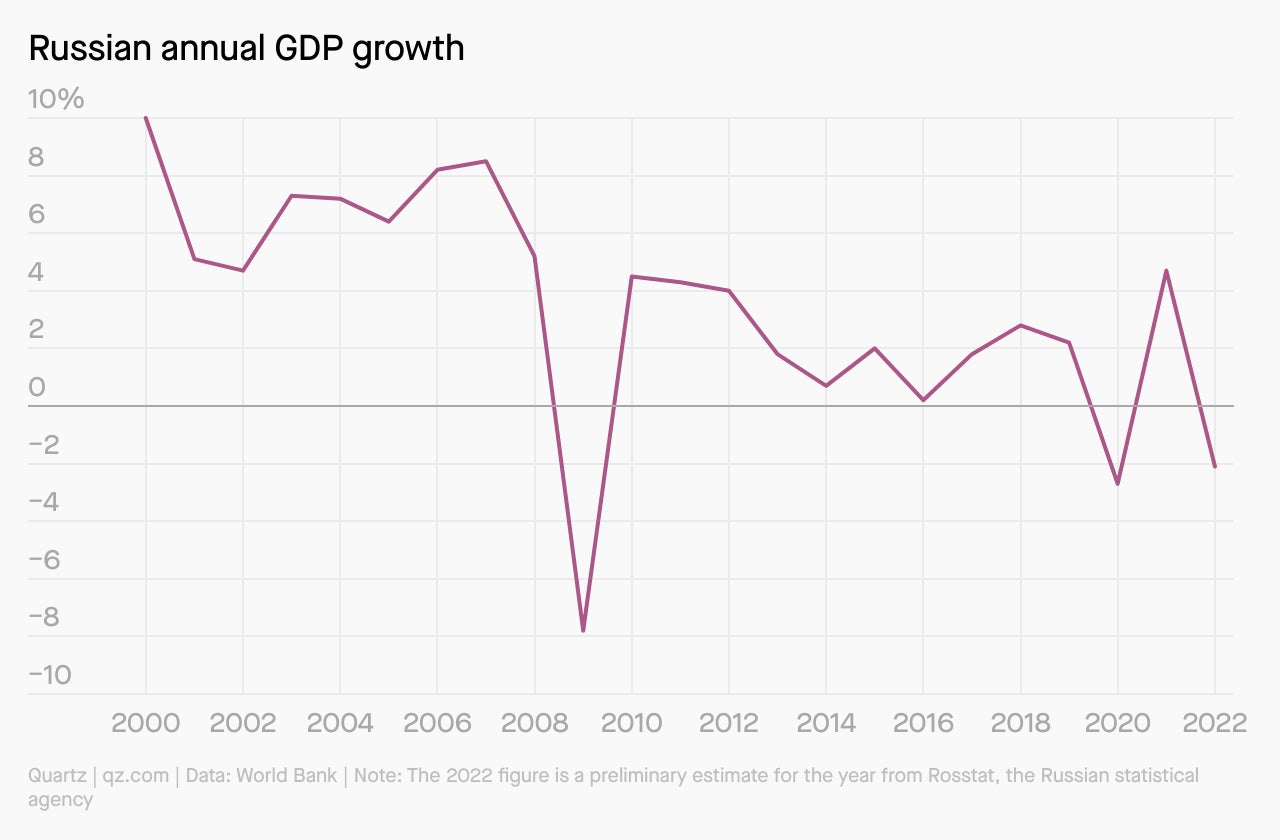

Given the breadth and comprehensiveness of the West’s sanctions on Russia, its economy has proven unexpectedly resilient. In 2022, its economy shrank 2.1%—much less than the 10-15% some of the forecasts made when sanctions hit last March.

In part, this was because Russia had spent years “sanctions-proofing” its economy. (The strategy had a catchy name, of course: Fortress Russia.) This involved companies and banks shedding external debt, thereby reducing their reliance on Western financing. Russia’s gross external debt shrank from 41% of GDP in 2016 to 27% in 2021.

Then, as the rest of the world adjusted to the war’s fallout, Russia did as well. Its imports of consumer goods started to flow through China, Turkey, and Kazakhstan. And as the West, and Europe in particular, tried both to sanction Russian fuel and to wean themselves off Russian oil and gas, Moscow found other big buyers: China and India. These sales were discounted, but commodity prices soared through most of 2022, which brought Russia a windfall. Oil and gas revenues, as a contribution to the Russian budget, actually increased by 28% in 2022.

This year, though, government expenditure will start stoking inflation, so Russia’s central bank is likely to begin hiking rates again in April. Oil and gas prices have declined dramatically, and the mild European winter has constricted Russia’s energy revenues. “And we are starting to see labor shortages, because so many people left Russia or were mobilized into the war last September,” said Liam Peach, a senior economist at the London-based research organization Capital Economics. Eventually, experts agree, the sanctions will bite and the Russian economy will buckle and sag. It’s just a slower-moving film than the West initially expected or hoped.

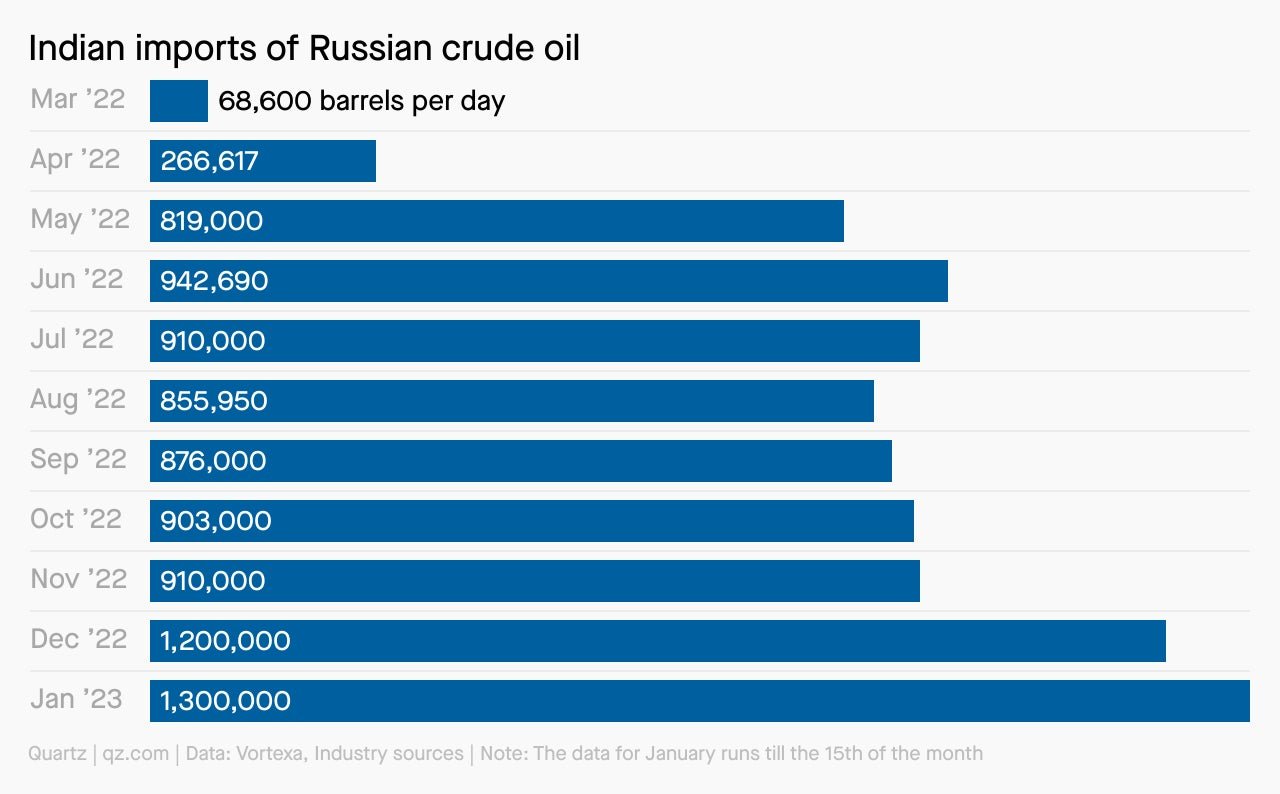

CHARTED: THE INDIAN BONUS

One unexpected beneficiary of the West’s sanctions on Russia has been India. In less than a year, the government has saved an estimated $3.6 billion by ramping up Russian oil imports. India bought this oil at a heavy discount, and Russia, suddenly deprived of other buyers, supplied it readily. Russia’s share of India’s oil imports had risen from a mere 2% in February 2022—before the war—to 27% in January. Not surprisingly, India’s energy policy has dictated its foreign policy as well. On the anniversary of the Ukraine invasion, during a UN General Assembly resolution urging Russia to end hostilities, 141 countries voted in favor. India abstained.

ONE ✈️ THING

How much does an average, fighting-age Russian man value his life? At the Centre for Economic Policy Research, two researchers came up with the morbid answer.

Tracking flights out of Russia in 2022, Antonio Avila-Uribe and Dzhamilya Nigmatulina found that the average prices of tickets rose from 40,000 rubles ($516 at the time) to 200,000 rubles. In part, though, this was a “demand shock”: the result of airlines suddenly halting services to Russia, drying up the number of flights out. But in late September, when Russia announced a partial mobilization of men for the army, no such demand shock was in play. The September spike in prices, the researchers assumed for their study, reflected “how much these men are willing to pay to decrease the threat of death.”

Another 2022 study had calculated that, for men aged 20-34, mobilization had increased the probability of dying within six months from 0% to 2%. Avila-Uribe and Nigmatulina correlated these odds to the excess price that men were willing to pay for their flights. “In this case, the value of life comes out as ten million roubles ($370,000 at purchasing power parity),” they calculated. Remarkably, this figure was not very far from the “5.3 million roubles cited in a 2019 Sberbank study using insurance data and the range of 5-7.4 million roubles that the government has chosen as compensation for the families of those who have died in the war.” To put a monetary value on a life—any life—feels profoundly sad, but war has precisely this lamentable way of reducing human existence to numbers.

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- How much money did India save in a year by buying Russian fuel?

- Experts predicted a wheat shortage after Russia invaded Ukraine. Why didn’t it happen?

- How Russia’s economy unexpectedly survived a year of war and sanctions

- Millennials are just as wealthy as their parents

- Biden has nominated Mastercard’s ex-CEO Ajay Banga for World Bank president

- Microsoft spent over a decade on the new Bing. Then ChatGPT happened.

- The growing US labor movement in 3 charts

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

🪖 On the ground. One year on, Ukraine continues to fight Russia’s invasion. Tens of thousands of volunteers, both domestic and foreign, have also joined the war. Esquire traveled across Ukraine for three weeks, painting a portrait of the motley characters who’ve chosen to enter the fray, ranging from US veterans to former flower shop owners. Though united through action, not everyone on the frontlines is there for the same reason.

🧠 The sentience question. Through many uncanny interactions, we’ve learned that AI chatbots can mirror human emotions. But does that mean they have feelings? An essay from Aeon says that theories of consciousness, to date, may be ill-equipped to tackle this question. However, measures of animal cognition could provide some guidance as AI presents a fresh challenge to our definitions of sentience.

💁♀️ Reality checkers. If you want to be on reality TV, get in line. More people than ever want to stir up drama on the small screen, and casting coaches have become the industry’s gatekeepers and starmakers. For former reality TV contestants, it’s also a logical (and lucrative) career move. The Wall Street Journal speaks to several veterans in the cottage industry about how they prep clients to nail their auditions.

⏳ Young at heart. Years pass, cakes get more candles, and we grow older. But many find that as their real age changes, their internal sense of time does not. In fact, on average, those over 40 often see themselves as 20% younger than they actually are. A story from the Atlantic explores why a perceptual gap exists when it comes to subjective age, including its psychological and cultural underpinnings.

💃 Topping the charts. Reggaeton, a rhythmic and lyrical blend of Afro-Caribbean and Latin music, emerged in Panama in the 1980s. Its underground popularity in poor Black and brown communities was long stigmatized in Spain. Now the genre has gained global fame, and lo and behold, Spanish artists dominate the genre. A story from Pitchfork explores the political tensions behind reggaeton’s mainstream success.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Stay strong this weekend,

— Samanth Subramanian, global news editor; Nate DiCamillo, reporter; Cassie Werber, senior reporter

Additional contributions by Julia Malleck