Africa needs a power play

Why are dozens of African countries so starved of regular electricity?

Hi Quartz members!

Last week, I had an opportunity to talk about the state of innovation in Africa to a group of students. They belonged to Wharton Africa Investing Partners (WAIP), a student-led initiative that supports investments in Africa by providing advisory, market research, and due diligence to Africa-focused private equity and venture capital funds, small- and medium-sized businesses, and entrepreneurs. One of the elements we touched on was power. A Nigerian student asked me if Kenya experiences the same power shortages that Nigeria, South Africa, and several other countries do.

I was pleased to tell him that extensive power cuts in Kenya are a thing of the past. More than 85% of my country’s electricity comes from renewable sources now. I did remember my final years of high school, in 2001-02, when there were national power outages every day, so that our school days ended at 7pm instead of the usual 9pm. We loved those days, not considering how problematic this was for the development of a country. For us, it was time to plait each other’s hair, tell stories, and learn new dances.

But only a few days after my presentation, all of Kenya was plunged into darkness: a five-hour blackout, caused by a fault on a transmission line. Perhaps I’d spoken too soon during my Wharton call.

This week, I was in Cape Town for a conference. Although Quartz had covered the South African load-shedding crisis, in which power is cut off to some as a way of staving off a system-wide collapse, I hadn’t thought too deeply about what 250 planned days of load-shedding this year means in reality. I was fortunate, because the place where I was staying as well as the conference venue had backup generators. As such, my chief annoyance was only that the wifi often refused to turn back on after a power interruption—something I experienced at both the conference and the airport.

With electricity access available to only 48% of Africa’s growing population, and the average firm in sub-Saharan Africa being affected by nine power outages every month, the continent’s development risks being slowed down by a lack of access to reliable power. In 2020, the World Bank reckoned that power shortages cost Nigeria $28 billion a year, or nearly 2% of GDP. But there are unquantifiable effects as well: the exodus of young, talented Nigerians, for instance, attributable in large part to their country’s economic difficulties. For a brighter future, African governments must first solve the problem of lighting their villages and cities.

BECAUSE BECAUSE BECAUSE

While each power-starved Africa country faces slightly different reasons for its shortages, some of the main common causes are:

🏚️ Aging infrastructure that cannot keep up with the demand of a rapidly growing population

⚡ Generation and transmission issues, which lead to lots of energy losses through the power network

🪓 A slow start in harnessing renewable resources in some countries, leading to an increased reliance on dwindling stores of fossil fuels

😟 Corrupt and sometimes highly inefficient authorities

🤝 Vested political and business interests that keep citizens dependent on diesel generators

🌧️ Low rainfall, affecting hydroelectric power

🥷 Vandals destroying gas pipelines and grid infrastructure

BY THE DIGITS: SOUTH AFRICA’S POWER CRISIS

$13 billion: South Africa’s expected economic losses from load shedding this year

250: Number of days in 2023 when South Africa expects blackouts

80%: Percentage of South Africa’s electricity that is generated from coal

6%: Percentage of electricity generated by nuclear reactors

45,000 megawatts: The installed coal power capacity of Eskom, South Africa’s power utility

22,000 megawatts: The coal power capacity that Eskom plans to retire by 2035

4,000-6,000 megawatts: Total annual power deficit in South Africa

$6.1 billion: Estimated cost of rehabilitation of power systems in the 2024-25 financial year

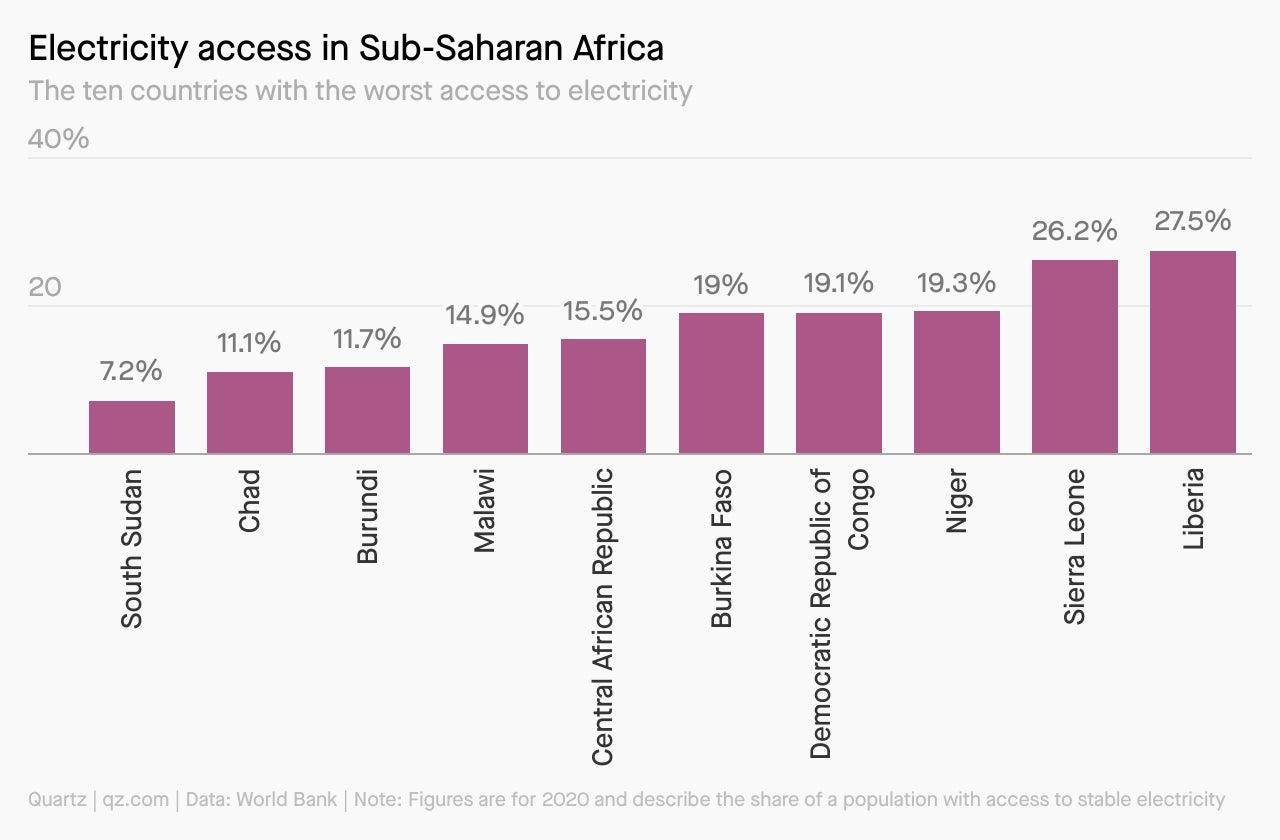

CHARTED

ONE 💡 THING

In a continent where 600 million people lack power, the diesel generator comes to the rescue of homes, industries, offices, and shops. At least 17 African countries have so many diesel generators that their collective off-grid capacity is greater than that of the power grid itself, according to data from Wood Mackenzie, an energy consultancy. It isn’t that these generators are cheap, necessarily; a primary health care facility in South Sudan, for instance, may spend $5,500 a year on diesel for its generator, money that a poor country can ill afford. But the absence of power altogether is a far worse prospect.

In that reliance on generators, though, there is hope. While countries build their grids up, generators can potentially be replaced by solar panels. They incur an installation cost, but the sunlight thereafter is all free. The off-grid solar market across Africa is estimated to be worth $24 billion. If solar spreads across Africa as comprehensively as mobile banking, the stress on national grids might ease up enough for governments to truly repair and expand them.

QUARTZ STORIES TO SPARK CONVERSATION

- The tech sector’s go-to banks are getting squeezed on all sides

- An Australian MP accused the Hillsong megachurch of using funds for private jet trips and luxury clothes

- Rich governments are not interested in funding preparations for the next pandemic

- Côte d’Ivoire is the highest taxed country in the world

- The leisure and hospitality industry is driving US job growth

- The US has too many prisoners and not enough community health workers. Here’s an idea to solve both problems

- A massive study of the pandemic found something surprising in global mental health: resilience

5 GREAT STORIES FROM ELSEWHERE

🎤 On repeat. Anyone looking for festival tickets this summer will have noticed that a number of recurring acts headlining Europe’s biggest music stages—most of them men whose biggest hits came out years ago. It’s not just a strategy to play on nostalgia, or to be sustainable; it’s the symptom of a lack of investment in fresh, and often female, music talent, as this Vice article points out. – Sofia Lotto Persio

📩 Kind regards. Now more than ever, ChatGPT is showing why the cover letter needs to die. Very few hiring managers read them, and if they do, they’re not necessarily checking cover letters for prose, just checking that you included one. Is it time to leave this dreaded writing process to AI? “Data from Indeed, which hosts job listings for job listings that traditionally require cover letters and those that don’t, shows that just 2 percent mentioned a cover letter,” Vox finds. – Michelle Cheng

🐦 Kiviaq. The Inuguhit of Greenland make a fermented meat staple known as kiviaq. It’s made by placing hundreds of dovekies, a small seabird, into seal skin, which is then buried under rocks for several months. Though the dish has gained international notoriety, often ranking high on “weirdest” food lists, it’s also attracted fans of fermentation around the globe. Atlas Obscura takes a closer look at the Indigenous culture and tradition behind the winter delicacy. – Julia Malleck

🇷🇺 Mother Russia. The realm of parenthood remains very much a woman’s world in Putin’s Russia. In a country that legalized abortion more than a century ago, a demographic collapse led to a glorification of women’s wombs and their reproductive abilities above all else—even state secrets, as one journalist’s IVF journey in Russia reveals. – Sofia Lotto Persio

👭 Engendered. The rise of India’s startup culture hasn’t much eroded the everyday sexism women face in the industry. This includes the way International Women’s Day is celebrated at many Indian workplaces, from HR teams asking female employees to “wear something pink or purple” to distributing lipsticks to commemorate March 8. Rest of World details how these companies are getting Women’s Day all wrong. – Shivank Taksali

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a bright weekend,

— Ciku Kimeria, Africa editor; Faustine Ngila, Africa correspondent; Samanth Subramanian, global news editor