Hi Quartz members!

Ever since the United Auto Workers (UAW) went on strike in the middle of September, the labor problems of auto manufacturers have looked bleaker and bleaker. After a week spent negotiating with Stellantis and General Motors, and seeing little progress, thousands more workers walked off the job on Sept. 22. Now 13% of the UAW’s 146,000 members are on strike. The wins, when they come at all, are small; after Ford met some union demands, the UAW refrained from taking more workers off the company’s assembly lines.

Both political parties are now courting the UAW’s blue-collar workers; this past week, Joe Biden became the first US president to join a picket line. (In 2019, some presidential candidates—including Biden—had joined the UAW picket line against General Motors.) For the UAW, there could not have been a more opportune moment to strike. In a tight labor market, auto workers enjoy great leverage. The American public, struggling with stubborn inflation for months now, is likely to sympathize with workers asking for better pay.

But the UAW’s strongest suit lies in the recent economics of the auto industry.

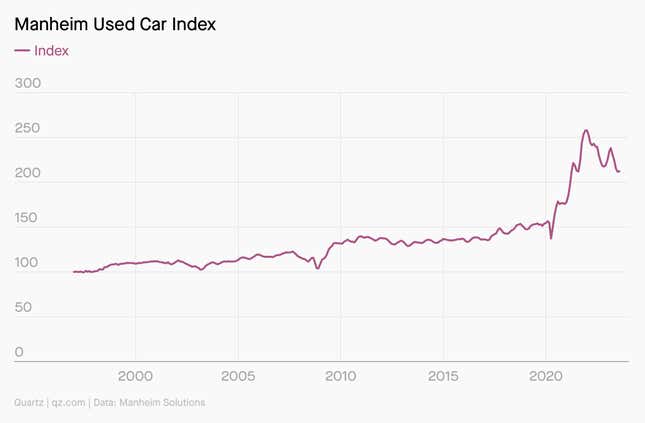

As the covid pandemic thinned out supplies of semiconductors, the demand for used and new cars rose, along with their prices, contributing heavily to a spike in inflation. After the supply chain normalized and demand settled, economists predicted that the labor market for auto workers would shrink. Companies that made and sold cars, they reasoned, might lay off employees to make up for lost revenue.

But car prices didn’t come down quite as much as expected. Part of the reason was simple supply and demand. Dealers, seeing their stocks of cars depleted by outsized demand, were able to take big margins on their sales, according to research from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. If the UAW strike does now end up raising the prices of cars, it will more likely be caused by dealers rather than manufacturers, wrote Alex Williams, a labor economist at Employ America.

The UAW seems to be keenly aware of the role that dealers have been playing in the automobile market. Earlier this week, the union targeted parts distribution centers that supply dealers with parts and components for repairs. Repairs are among the most profitable aspects of a dealership’s business. By pinching dealers, the UAW is hoping that they, in turn, will pressure auto manufacturers to negotiate with striking workers, making a deal more likely still.

CHARTED: THE USED CAR PRICE WHIRLWIND

SUPPLY CHAIN OR POLITICAL TOOL?

The auto workers’ strike underscores the vulnerability of just-in-time supply chains, which don’t prioritize holding inventories. For instance, suppliers now need to pay more to store auto parts that idling assembly lines can’t use. As demand for these parts wanes, the effects of the strike will stretch long after it has ended, Ann Marie Uetz, a partner at the law firm Foley & Lardner, told Supply Chain Dive. Companies that sell specialized parts and raw materials to manufacturers like Stellantis, Ford, and General Motors might see their modest balance sheets damaged or destroyed by the strike.

But these disruptions shouldn’t be blamed on workers. When employees receive a diminishing share of their company’s total earnings, amid rising living costs, it impacts their real wages. This strains the savings of blue-collar workers, generating greater inequality and intensifying class disparities, which can lead to societal unrest.

Meanwhile, in the post-pandemic world, it’s clear that weak supply chains can be such a huge vulnerability as to amount to a national security concern. When energy prices spiked amid global inflation, Russia invaded Ukraine, knowing that Western nations would be reluctant to place heavy sanctions on Russia and risk further price increases for their citizens.

The UAW has absorbed these lessons. In targeting parts suppliers, it is applying a similar supply chain squeeze—albeit for much more honorable ends.

ONE 🔥 THING

The UAW’s picketing, driven by wages but also by anxieties over the car industry’s transition to electrics, is one of several recent labor disputes clearly tied to climate change, argues Adam Met, the executive director of a climate research nonprofit called Planet Reimagined. America’s “hot strike summer” and the global impacts of climate change, Met wrote for Quartz, might give US workers more leverage, not less.

Labor fights are an inevitable feature of deepening climate change. How they get resolved will shape our energy transition and other important components of the response. Will we see more Teslas on the road than EVs from the Big Three union manufacturers? Will our packages continue to land speedily on our stoops as delivery workers toil in extreme heat? Can we expect more NAFTA-scale transformations of trade as nations try to navigate worsening climate conditions? And when will I get my sriracha back? These are all questions that climate change poses.

The answers won’t be found today on the picket lines. But there are solutions. Whether they materialize depends on how employers, governments, and the labor movement recalibrate for a warming planet.

Thanks for reading! And don’t hesitate to reach out with comments, questions, or topics you want to know more about.

Have a strikingly great weekend!

—Nate DiCamillo, US economics reporter