Dear readers,

Welcome to Quartz’s newsletter on the economic possibilities of the extraterrestrial sphere. Please forward widely, and let me know what you think. This week: space vs. counter-space, Soviet design and the thicc Dragon of the moon.

🚀 🚀 🚀

Earlier this month, the US Space Force deployed its first, and only acknowledged, offensive weapon: A mobile satellite jammer.

The power to block satellite communications is a key “counter-space” ability—the act of denying an enemy the use of the tools it has in orbit. Jammers aren’t the only thing that can do that: Militaries could also use a ground-launched anti-satellite missile, an orbitally-placed weapon, a laser, or a cyber-attack.

As space technology becomes more important in conflict—the US, in particular, is deeply reliant on it—more countries have developed such counter-space weapons.

Frustration with the US Air Force’s slow response to this trend is a major reason the US government decided to create the Space Force in 2019, according to Brian Weeden, the director of the Secure World Foundation. Last week, the think tank released its annual assessment of how countries plan to stop their rivals’ space activities.

India, China and Russia have all tested anti-satellite missiles in recent years. Russia, China and the US have been deploying maneuvering spacecraft that can approach, inspect, spy on, and perhaps even destroy other satellites. Many countries, including the US, Russia, China, and even Iran, have been caught jamming satellite navigation systems.

China is the only nation that fields an operational anti-satellite missile, though both Russia and the US have weapons that could quickly be re-purposed to take out a satellite. That may seem like the US is already left behind, but it’s the wrong impression, Weeden says. China’s military doesn’t rely as much on space. So in a war, destroying its satellites isn’t a top priority. And using kinetic weapons in space generates new and unpredictable space debris that could become a problem for every other actor in orbit.

“We’re sort of programmed to think about this in the nuclear context of, ‘whoever has the most bombs wins.’ That’s totally not what’s going on here at all,” Weeden said. “This is more of your standard military cat and mouse game, all about saying we need to have a capability to have this sort of effect, [and] there’s multiple ways to achieve that effect.”

That leaves the newly-formed Space Force with two big questions: How can it make sure the military spacecraft it buys are ready for a world of adversaries with a Swiss Army Knife of tools to mess with them? And how can it make sure the people who design, operate and track these spacecraft know what to do when those tools start being used?

🌘 🌘 🌘

Imagery Interlude

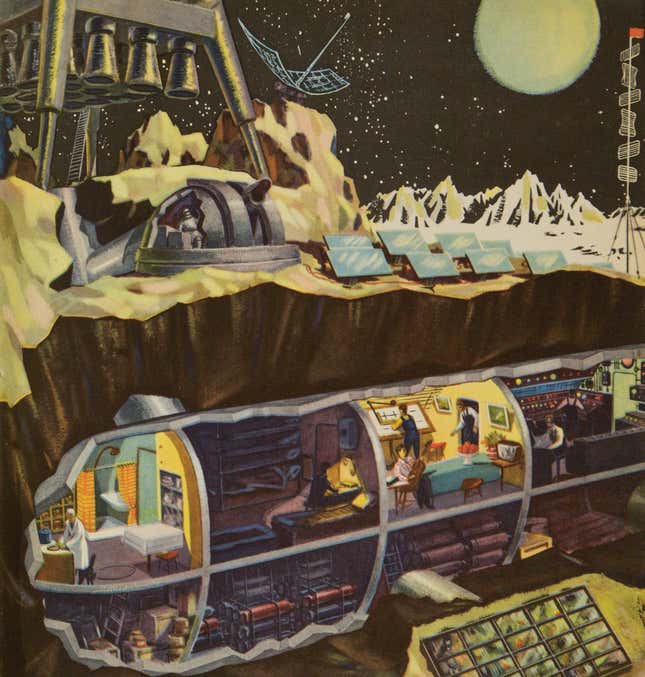

While sheltering-in-place, my escapist fantasies have been driven by a very cool book—Soviet Space Graphics, published this month by Phaidon. Alexandra Sankova, the founder of the Moscow Design Museum, has assembled fascinating imagery published in the Soviet Union during the Cold War space race. It even includes an enviable quarantine shelter:

Read more about the book—and see more images—in my interview with Sankova.

🛸 🛸 🛸

🚨 Read this 🚨

Where will the next generation of engineers come from? The coronavirus pandemic is leaving an indelible mark on our classrooms and our workplaces. This week’s special field guide for Quartz members examines the pandemic’s long-term consequences.

🚀 🚀 🚀

SPACE DEBRIS

Gateway to nowhere? NASA announced, a bit out of the blue, that it had hired SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket and a new spacecraft called Dragon XL to bring supplies to the Lunar Gateway, a proposed moon-orbiting space station. The timing is interesting, since NASA just made the Gateway an optional element in its plan to return to the moon—a bit like hiring FedEx to deliver components to a factory you’re not really sure will be built. Eric Berger sought some clarity from NASA, and the answers were, well, not clear. “This is where it kind of gets into the, question of, what is our 2024 plan? It’s kind of still in the works,” says Dan Hartman, the Gateway program manager, when asked about the timing of all this. Meanwhile, SpaceX won’t answer any questions about the mooted Dragon XL, which will likely require years of design and testing before it can fly.

Virgin Vents. Virgin Orbit, the satellite-launching spin-out of Virgin Galactic, will begin making simple ventilators designed by a team of physicians and bio-engineers. The devices are intended to ease the pressure on hospitals, which face swelling ranks of Covid-19 patients who require assistance breathing. These ventilators should be cheap and fairly speedy to manufacture, in contrast to more sophisticated machines that aren’t expected to be in full production until a month from now.

OneWeb’s rivals cheer bankruptcy. If you want to see someone dancing very energetically on a competitor’s grave, check out this interview with long-time satellite exec Tom Choi in SatelliteToday about the bankruptcy of OneWeb, which until recently was trying to build a huge constellation of satellites in low-Earth orbit to provide broadband internet. Choi’s company wants to use small geostationary satellites to do the same thing. Come for his argument that low-Earth orbit ground stations are too expensive and power-intensive to expand broadband access, stay as he works out personal issues with Greg Wyler, Elon Musk, and Jeff Bezos, the main proponents of low-Earth orbit systems.

An extra astronaut for Crew Dragon’s second flight. There is still hope that SpaceX’s Crew Dragon will carry is first two astronauts during a test flight sometime in May, with training, final tests and simulations in full swing. And if that all goes well, an operational mission will lift off later in the year. One sign of confidence is that the US space agency has assigned another astronaut, Shannon Walker, to join the existing crew of Michael Hopkins, Victor Glover, Jr., and Japanese astronaut Soichi Noguchi on the trip. The extra passenger should help with staffing problems on board the International Space Station caused by delays in getting NASA’s commercial crew program flying.

Your pal,

Tim

This was issue 41 of our newsletter. Hope your week is out of this world! Please send your favorite space art, most accurate predictions of space business disaster, tips, and informed opinions to [email protected].