As India’s Covid-19 crisis becomes insurmountable, the Narendra Modi government has been widely criticised for trying to filter what the world hears about the worst pandemic outbreak anywhere on the planet.

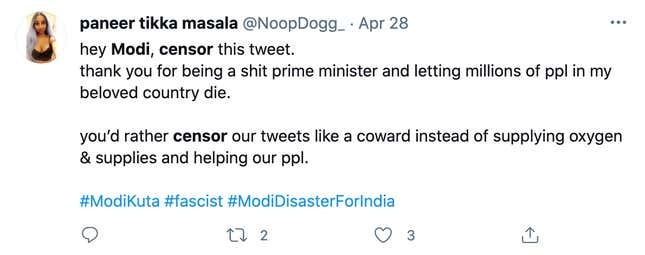

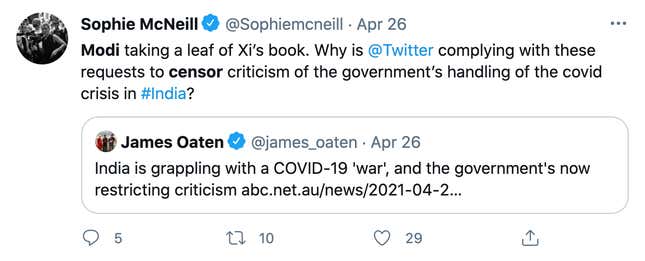

In the last week, the government has sent notices to Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to take down around 100 posts and block several accounts that were discussing the pandemic and its management. On April 23, at the behest of the Indian government, Twitter blocked over 50 tweets from politicians, filmmakers, and others criticising the mishandling of the pandemic.

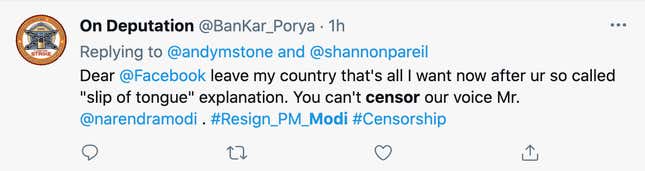

Earlier this week, the #ResignModi hashtag was blocked on Facebook for hours. The social media platform later restored it and said it was a “mistake” and “not because the Indian government asked us to.” Facebook’s policy communications director Andy Stone did not reply to Quartz’s query on whether this error was caused by an algorithm or a human.

While such mistakes are not entirely impossible, people aren’t buying Facebook’s reasoning mainly because the Modi government has a history of shutting down critics.

In the past, this government has got social media firms to clamp down on criticism about the farmers’ protest, the Citizen Amendment Act, the revocation of Article 370 in Kashmir, and more. It has also threatened social media platforms if they did not follow instructions.

Buzzfeed journalist Ryan Mac called this “mistake” by Facebook “truly bizarre and worrying.”

The Twitter battle between Modi and his critics

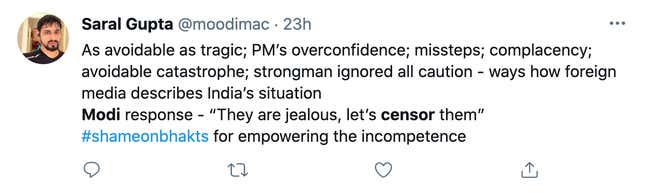

The government’s justification for getting these posts removed is that it is trying to control the spread of misinformation and curb panic. But many believe the real motivation is to suppress and intimidate.

The goal, many said, is to take control of the public narrative. “Earlier, what we witnessed was shoot the messenger,” Sevanti Ninan, a media critic, told DW. “Now, the government is shooting the platform too.”

Some of the tweets that were taken down this week were from members of political parties that oppose Modi. These include posts from Indian National Congress member Revanth Reddy, All India Trinamool Congress member Moloy Ghatak, and anti-Modi freelance journalist Pieter Friedrich, among others.

These tweets mention rising cases and deaths, a shortage of medicines, accompanied by photos of Modi’s election rallies even as the Covid wave became uncontrollable, scores of funeral pyres, and patients struggling outside hospitals.

There’s no denying that all these claims are accurate.

Cases and deaths are skyrocketing despite severe undercounting, medicines are running out, finding a hospital bed is becoming next to impossible, and elections are continuing in full force.

How can the Indian government takedown Twitter posts?

The Section 69A of India’s Information Technology Act, 2000 authorises the government to block any digital information “if it is satisfied that it is necessary or expedient to do so, in the interest of sovereignty and integrity of India, defence of India, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states or public order or for preventing incitement to the commission of any cognisable offence.”

This law gives Modi government a nearly free run to dictate what stays and what is removed from Indian social media.

On Twitter’s side, the company says ”when we receive a valid legal request, we review it under both the Twitter Rules and local law. If the content violates Twitter’s rules, the content will be removed from the service. If it is determined to be illegal in a particular jurisdiction, but not in violation of the Twitter Rules, we may withhold access to the content in India only.”

But a glance at Twitter’s relationship with the Indian government proves the two are constantly in a tug of war.

In February, the government threatened Twitter’s officials with jail time for not taking down specific tweets and handles related to the farmer’s protest. When there was a delay in Twitter taking down the material, several prominent leaders in Modi’s cabinet started endorsing a rival home-grown app, Koo—India’s Parler—and asking their followers to join that platform to connect with them. Perhaps fearing loss of business, Twitter, which has over 17.5 million users in India, restricted the visibility of some hashtags and penalised 500 accounts but it continued to push back, refusing to limit accounts of news outlets, journalists, activists, and politicians, citing free speech.

In 2019, too, the government had warned that Twitter executives could face up to seven years in prison if the platform didn’t follow content removal instructions for what the government deemed “objectionable and inflammatory.”

Facebook, which has 20 times more users in India than Twitter does, seems to have more crafty intentions.

Is Facebook currying favour from Modi government?

On April 28, when Facebook temporarily banned #ResignModi, more than 12,000 posts got hidden for hours. That it happened accidentally is plausible. Facebook has earlier accidentally blocked and then restored hashtags like #savethechildren and #sikh.

But skeptics have a reason for why they don’t trust Facebook.

The world’s largest social media site, led by Mark Zuckerberg, has been accused of pandering to Modi’s BJP in the past. It has taken down pages of BJP rivals and turned a blind eye to BJP flouting ad rules. It’s allowed fake accounts to artificially boost a BJP politician’s popularity.

Last October, Facebook’s India public policy head Ankhi Das had to step down following allegations that she had asked staff members to not apply hate speech rules to posts of BJP politicians.

And on the day of the #ResignModi debacle, Zuckerberg was silent on India. Instead, he was chatting about memes on the other side of the world.