It’s boom times for US defense contractors—and they can’t keep up with demand.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and China’s military build-up have US lawmakers shelling out billions to buy new missiles, aircraft, tanks and helicopters to support allies and prepare for future conflict. Including the most recent tranche of funding passed in December, Congress has enacted about $110 billion in aid to Ukraine, about $40 billion of which will go toward weapons transfers and purchases.

That’s putting stress on the makers of modern weaponry. Consider that some 1,600 Stinger missiles, used by individual soldiers to attack aircraft, were sent to Ukraine from American stockpiles, but the US stopped making them in 2003. Raytheon, its manufacturer, has restarted production, but doesn’t expect to deliver the weapons in large numbers for a year or more.

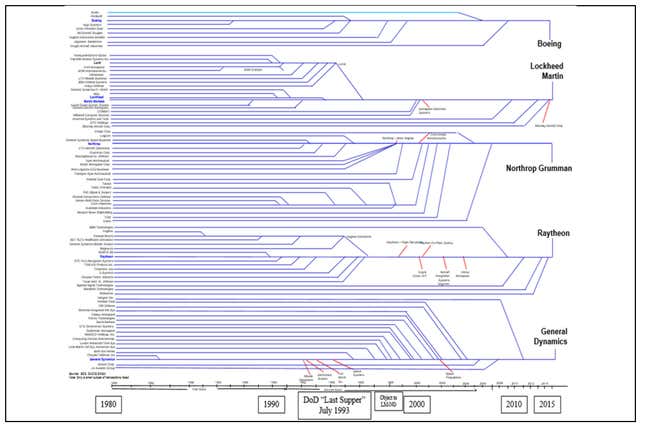

Raytheon is one of just five major defense contractors and that number is now getting a lot of attention at the Pentagon, which is clamoring for more competition in the defense industrial base. A report issued last year says that the Department of Defense now depends on just five prime contractors today, compared to 51 in the 1990s. Take a look:

This was, in part, the result of good news: The great consolidation of the weapons industry in the US was driven by spending cuts following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. The “Last Supper” mentioned in the chart above was a meeting between US Defense Department official William Perry and the CEOs of major defense contractors, during which Perry said the companies should consolidate or die as weapons spending would fall.

Some of this consolidation, however, was driven by frenzied deal-making, low interest rates, and an arguably lax approach to anti-trust. Faced with a sudden demand for weapons, the Defense Department now wants to push back against mergers that could leave the military dependent on just a handful of critical suppliers.

The issue isn’t so much that the US isn’t running out of weapons, but that its transfers to Ukraine are stretching its own stockpiles, which it needs to train and be prepared for unexpected conflict. For one example, experts estimate that the US has given more than a third of its stockpile of Javelin anti-tank missiles to Ukraine, which will take years to replenish.

Aerojet’s agonizing hunt for a buyer

One reason it will take so long are production delays at Aerojet Rocketdyne, which makes rocket motors for everything from NASA’s Space Launch System moon rocket to Stinger and Javelin missiles.

The Defense Department stretched its anti-trust muscles in 2022, when it supported a FTC decision to block Lockheed Martin from purchasing Aerojet. But the company’s struggles have led to unusually direct criticism from larger customers like Raytheon, whose CEO recently called for “adult supervision” at the company.

But the Pentagon doesn’t really have another choice. Whereas there were, as recently as 2000, seven companies in the US making solid rocket motors, now there are just two—Raytheon and Northrop Grumman, which (naturally) got into the business by buying the company Orbital ATK in 2018.

Now, Aerojet looks likely to be acquired by L3Harris, now the sixth-largest defense contractor by revenue. That weird name signifies that it is the product of the consolidation trend—the three L’s are for two former defense executives and Lehman Brothers, the defunct investment bank, who created the company in 1997 and merged it with Harris, a long-time defense contractor, in 2019.

This acquisition looks likely to be approved because L3Harris is not already a maker of rocket motors, and because a larger company behind Aerojet could help get Javelins to Ukraine faster. But more M&A seems unlikely to result in cheaper weapons or larger production rates in the long-term, which is why the Pentagon wants more start-ups and subcontractors getting into the business of weapons, and defense contractors want better long-term planning.